Article originally published in New Empress Magazine.

Being old and feeling almost excavated from some grainy piece of earth, silent horror has the unnerving sense of being a genuine piece of documentation. No doubt unaware of it at the time, Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan: Witchcraft Through The Ages (1922) is a film that so embodies this accidental aspect that viewing it recalls the feeling of Ash’s discovery of The Book of the Dead in Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1981); the discovery of some ancient curio or artifact.

Häxan has the aura of a genuine “found footage” film; a warning to the curious for those delving into the realms of black magick and a world of Devil worship, sex and death. The year previously, Scandinavia had already made its mark in horror with Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage, which hinted at the potential in folk legends and tales but used it for more metaphorical purposes. It is Häxan that garners the attention, being a film of startling and innovative filmmaking; a grainy documentary about witchcraft that sees the birth thematically of both occult horror and folk horror.

%2002.jpg)

The film is about belief systems and how they control the actions of the people who follow them. Documenting the world surrounding witchcraft, it looks at the supposed occult practices and re-enacts them for the benefit of our curiosity. Devils, demons, sacrifices, medieval skulduggery, witchcraft, methods of ancient torture; they’re all here.

While trying hard not to run away with the idea that the film is about realism, it also acts as an informative piece (though the truth about these ancient practices is most definitely stretched for entertainment purposes in the later chapters of the film). It is here in this one action of Christensen’s, the distortion of truth to create a recognisable fantasy, that gives rise to possibilities of the occult in horror. The idea that evil is created through people, their actions qualified by their beliefs and their lack of scientific understanding, is something that sub-genres would immerse themselves in and return to again and again; grounding the films in particular eras, styles of communities and different forms of paganism.

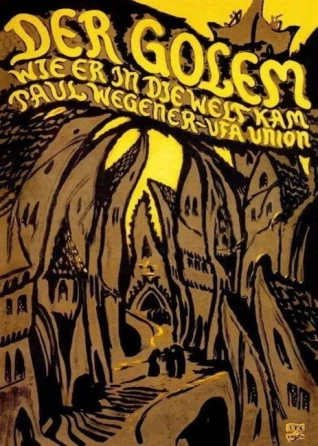

Häxan’s initial influence is clear on the first wave of horror films towards the end of the silent era and into sound, though it is not vital to the sub-genres. The same feel for the supernatural is also captured in F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), Carl T. Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931), and Robert Weine’s The Hands of Orlac (1924). Yet these fail to capture the mysticism or truly occult nature of Häxan. Der Golem (1920) by Paul Wegener also predicted the potential fear over folklore but other than being a well made film, it did little to push the sub-genres onward.

It is not until the horror boom of the 1940s that we really start to see themes first explored by Häxan emerge. Helped no doubt by widening availability of Gothic literature, studios became tiresome of the monster pictures that had dominated thanks to Universal since Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) and started to make more interesting and down to earth horrors. Even before this, Bela Lugosi was delving vaguely into the occult, more specifically voodoo, in Victor Halperin’s White Zombie (1932). However, this voodoo edge gives both it and Hammer’s later The Plague of the Zombies (1966), a different flavour.

Occult

The first successful foray into territory opened up by Häxan is from the studios of RKO and their maverick producer Val Lewton. Producing a handful of films that defined the first new wave of occult horror, Lewton and directors, Jacques Tourneur and Robert Wise, created thrillers with occult themes in mind.

However, a new and refreshing aspect was added to the mix, moving it still further from Häxan’s original premise of mere evocation of an era. Häxan’s ending hints at what Lewton eventually created; that is to say moving thematically to people of the modern day and their curiosity with the occult through a more psychological approach. Cat People (1942) may not explicitly be about occult actions but the supposed possession of the main character comes from tales of folklore in her native Serbia. More in line with the occult theme is The Seventh Victim (1943) which follows a young woman as she uncovers an underground satanic cult while searching for her missing sister. This is first real step in developing the idea of tradition as something to be feared (as a viewer) and sociological progress as a terrifying prospect for the characters in the film. These are ideas that occasionally crop up in occult horror but dominate folk horror.

Though Lewton did not produce it, this mini revival can be seen to peak in Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (1957). Based on the M.R James short Casting the Runes, it is a perfect contextualisation of Häxan’s main themes. Night of the Demon follows Dr John Holden (Dana Andrews), a scientist attending a lecture in London to expose the apparent occult fraudster Dr. Julian Karswell (Niall MacGinnis). Karswell can be seen as a modern day witch and is the first example of the occult being tied into bourgeoisie lifestyles; something really pioneered by the novels of Dennish Wheatley and that the genre would cement on screen in later years. Curses are cast and a demon is summoned, all directed with an eye for detail by Tourneur, making Night of the Demon the first truly great exponent of Häxan’s beastly creations.

Following on from this is Sidney Hayes’ Night of the Eagle (1962) which wittily transplants the use of black magick and occult actions into the simple household affairs and keeping up appearances of the early 1960s. Often underrated, Night of the Eagle shows the human side to black magick, using it in an attempt to help garner social standing rather than just for the general love of chaos shown by the wives and witches of Häxan. Perhaps also because of its similar title, the film hides away in the shadow of Night of the Demon even though it has a rich, intelligent analysis of gender relationships and power dynamics in the most Freudian of detail. Hammer also had their take on the aspect of witches in 1966’s The Witches (scripted by Nigel Kneale) but this ties nicely into the more upper class elements that would become another trait of the genre rather than erring on the side of the overtly supernatural.

From here on, the occult becomes a pastime of the rich and idle, as well as West London hippies and free love fanatics. Hammer Horror’s The Devil Rides Out (1968) is a perfect example of the Wheatley vision with just about every character owning a mansion and knowing something about Satanism and witchcraft. Though all sorts of nasty beasts are summoned, like its title suggests, at the heart of this film is Lucifer himself. The Devil gradually becomes a fashionable theme to explore, not just in occult horror but in the many mainstream horror films too.

Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) is the most subtle of occult films, with very little screen time dedicated to actually showing any witchery. The characters are rich again and this trend oddly extends to the other big Devil themed films of the period; The Exorcist (1973) and The Omen (1976). Häxan’s devilry is adapting to the modern times and finding solace in the richest, and arguably most excessive, strands of society. This is the polar opposite of Häxan’s characters yet this juxtaposition between interest in the occult and wealth seems a natural progression. The characters of these films seem to be performing these atrocious acts out of boredom and the Devil clearly sees the most idle to be the rich in films by Polanski, Freidkin and Donner even if they are not all inherently evil to start off with.

One last film to look at before moving on to folk horror handily bridges a gap. Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) perfectly intersects between the two very similar sub-genres. Again the Devil is trying to be summoned but this is more in line with the traditions of Häxan than the previous films. Medieval Britain is the setting and the film plays into this, almost asking the viewer to believe this to be an accurate account of Devil possession in spite of really reflecting the post-Charles Manson era than anything else (though it doesn’t try to be as purely documentary like as Häxan). It also mixes in the atypical folk horror message of people being the true forces of evil and the misguided in their actions. Even with its countryside setting and Winstanley (1976) style visuals, the horrors of an isolated belief system gone mad are central and these aspects are what give folk horror that edge of difference from occult while still keeping in line with the ideals of Christensen’s film.

Folk

Folk horror is a sub-genre so synonymous with British film that it is surprising to find its birth in a Swedish/Danish production. There’s little doubt that Häxan’s telling of the old ways of life and occult tradition in rural communities lead to the birth of the sub-genre itself.

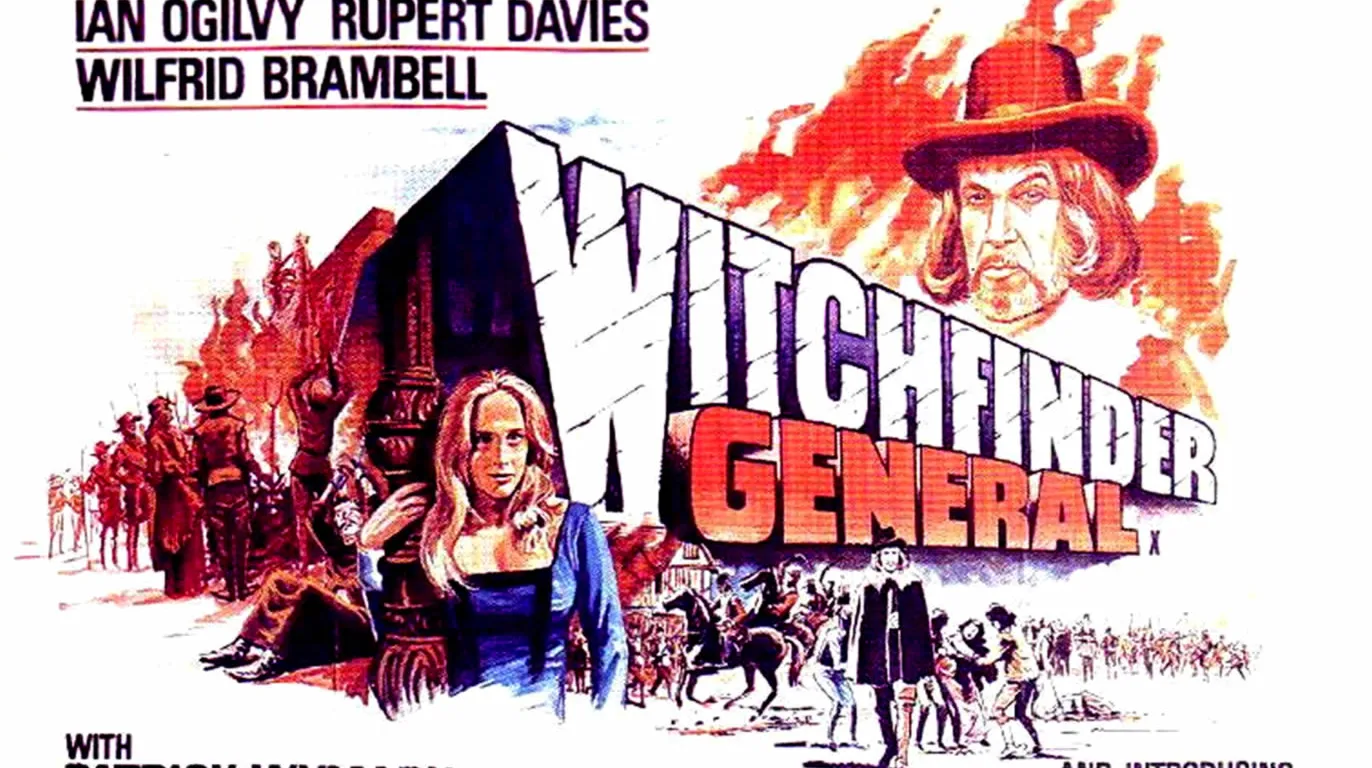

The late sixties are where the genre starts to fully form with the release of a handful of films chiming with the era’s folk revival that occurred in the music scene. Tigon Films released some of the most obvious and best of these. Their Blood on Satan’s Claw may have an occult edge but Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968) dismisses all of that and harkens to the nasty realities of Mathew Hopkins’ witch hunt. The brutality and torture of convicted witches shown in Häxan is taken to the extreme in this very bloody film. People again seem to be the root of the cause, and their paranoia over the occult gives way to the atrocities, marking it out as a folk horror of the purest kind.

Tigon produced several films in similar ilk but never truly matching the quality of these two films. Reeves’ The Sorcerers (1967), Ray Austin’s Virgin Witch (1972) and Vernon Sewell’s Curse of the Crimson Altar (1968) all have the grainy dirtiness of folk horror but do not quite fulfil their potential. A better film to link on from Witchfinder General (by means of Vincent Price) is Gordon Hessler’s Cry of the Banshee (1970) which seems like a homage to Witchfinder General but with an added supernatural edge (as well as a bizarre strain of slap ‘n tickle comedy). Also in similar vein is Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) which has a British edge to its torture belying its setting in France.

The last and probably most famous British folk horror to mention is Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). Much has been discussed about this odd little film, yet its links to Häxan seem the most honest. Häxan’s main trick in scaring its audience is distorting the past to create horrors. The Wicker Man instead distorts the present and provides a believable, pagan community still alive and kicking as a product of the early 1970s counter culture movement. However, there is no Devil worship and at the heart of a film sits a genuine reason for the actions of the people rather than just boredom. Their belief system dictates that sacrifice is needed to make their crops grow and there is no doubt that the folk of Häxan shared similar belief systems. This vein of horror has now been well mined with a poor remake, Hammer’s take on the genre in David Keating’s Wake Wood (2011), and even a sequel in Hardy’s The Wicker Tree (2010).

Away from Britain, one can’t help but feel that the isolation of communities seen in the genre is part a mechanism used outside of the sub-genres. Surely the results of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) are due to the same isolation that results in the sacrifice in The Wicker Man? America has produced the most obvious nod to Häxan with Haxan Film’s debut, The Blair Witch Project (1999), proving that there is horror in the traditions of all countries. Even older films like Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter (1955) have a particular outback to them that provide the same heady mixture of weaponised belief and isolation as British folk horror, albeit achieved in a different way. Japan’s folk horror in particular has some fine moments, too. Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964), Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968) are just a few examples of different traditions in another country’s folk horror. Even Hideo Nakata’s Ringu (1998) is based around a M.R. Jamesian, urban myth; a modern, urban folk horror if ever there was one.

Conclusion

Though some of the films mentioned may bear only a fleeting resemblance visually to Häxan, thematically they all owe Benjamin Christensen’s film some debt. Using tradition as a basis of fear and a starting point for a resistance to cosmopolitan progress, an examination into occult practices and a look into witchcraft and devilry, Häxan establishes much in the way of thematic material, even though horror at the time was still establishing itself properly as an independent genre in its own right. Maybe one day, the traditions of our time will be used successfully to scare future viewers and make them feel relieved they do not live in the barbaric Noughties, perhaps even giving rise to a whole new wave of horror sub-genres set around smart phones, social media and terrible music. That, however, is a though too scary to contemplate.

And I would put in a shout for Ben Wheatley’s Kill List to bring things up to date; the final third of which morphs into Occult Horror, taking Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut occultist gathering up a year.

I haven’t seen kill list so will have to check it out!

As for Eyes Wide Shut, it’s film I’ll be expanding on in the book hopefully, in the american section.

Adam

You’re writing a book?

I am indeed, though it won’t be ready for a while and may well never get printed haha.

You should title it “Dam Gud Movies”

Reblogged this on gingersnaps and tattered souls.

My apologies for that. Not too sure what happened. I’m grateful all the same though! Thank you for your kind words.

Adam

I’ve noticed a few recent films delving into the occult and folk horror subject matter, most notably, The Last Exorcism and Paranormal Activity 3.

Indeed!

It appears to be an area that is gradually coming back into fashion.

Hello Adam

“It appears to be coming back into fashion.” You may be interested in this: http://blogs.qub.ac.uk/folkhorror/

It’s a folk horror perspective at Queens University in Belfast in September 2014.

Really liked your blog: some thought-provoking ideas here. Have you seen Nic Roeg’s Puffball (2007)?

Thanks!

I have indeed seen that event and plan on sending some abstracts to it 🙂

I haven’t seen Puffball but it looks excellent!