Over time, we become strangers to ourselves in Polaroids. We take them, not to create memories, but to help retain them. Sometimes this is unnecessary. At other times, it is essential if we want to remember moments in our lives. This is an idea realised perfectly in Christopher Nolan’s debut feature, Memento (2000).

It is a film that essentially sits on the cusp of the digital revolution, making it feel like a last American gasp (albeit directed by a British director) of analogue normality, heightened further by being shot on film. Cinema would soon diverge on mass into the world of empty o’s and lost 1’s.

Memento‘s exploration of memory centres on the use of a Polaroid camera, and is the most extreme use of photography to attempt to build a reliable memory in cinema. The narrative is further complicated by showing multiple timelines travelling in different directions, marked by differing aesthetics, in particular colour.

The film follows Leonard Shelby (Guy Pierce), a former insurance lawyer in search of a criminal. His wife Catherine (Jorja Fox) was raped and murdered, and, while Shelby managed to subdue and kill one of the attackers, the other hit him and escaped. As a result, Shelby is suffering from anterograde amnesia, meaning that he has regular short-term memory loss every fifteen minutes or so, and is unable to construct and retain new memories without some assistance.

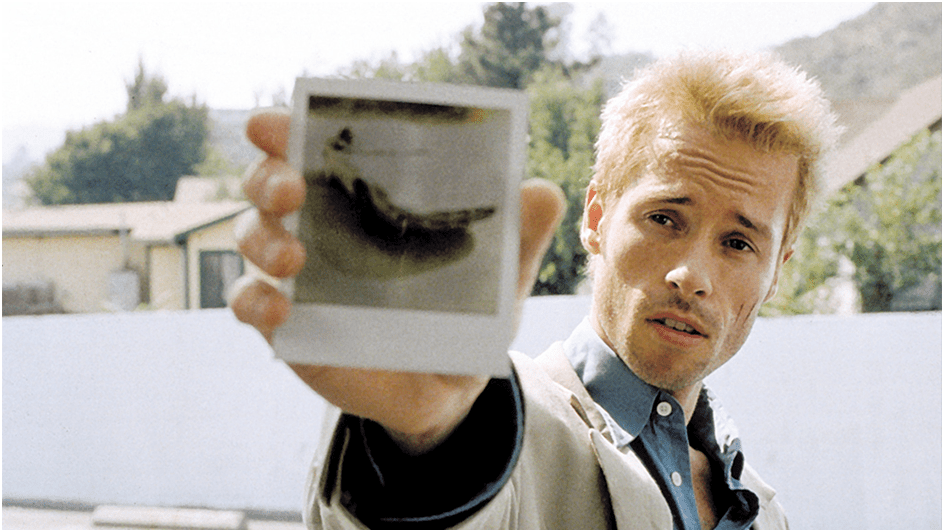

He resorts to a number of strategies to deal with this, from tattoos to Polaroids. It is the latter that are the more interesting. Their importance is clear as most of the promotional material for the film features mosaics of Polaroids; a world built on analogue fragments. A shot of a Polaroid even opens the film and the scenario is interesting as it shows the drama’s main conceit; a reversal of memory and time.

The visual of the film is a Polaroid of a bloody scene. On show is clearly the upper body of a man on the floor, trapped between two grimy walls covered in blood. As the credits roll, the hand holding the Polaroid shakes it. Two things are apparent: that the Polaroid is showing what is directly behind it, and that, with each shake, its image is fading rather than developing. Time is in reverse.

Instead of hindsight, the photograph possesses foreshadow, a hint of what is to come. It is a heady device, for the film is offering us a chance to see what is going to happen before it has happened, while at the same time playing what has happened in reverse. The murder that is about to take place has already occurred, but is only shown in the Polaroid. It is only when the image is magically pushed back into the camera that we see it replaced with a gun which soon sucks the bullet out of a man’s head.

There is a refreshing practicality to the use of Polaroids in the film which seems a last hurrah in terms of their genuine ease being the main reason to use them. Digital ease would soon replace it in everyday photography. Perhaps Shelby would have been better equipped had he used a digital camera contained in a modern phone, but imagining the scenarios with the natural lack of drama of digital technology is scarcely comprehensible.

Instead what we have is a man who carries his memories around with him physically. Rather than putting them in a box and out of the way like most people, he is forced to keep them around to make sure he actually remembers the most important things about his current situation. He may even be one of the few screen characters to actually use the Polaroid’s designed frame for captioning, annotating each image just to be sure of the memory they contain.

If ever you have felt heavy with memories – upsetting, bad, unbearable memories – then the feeling will be one that is recognisable. The film realises literally what Patrick Modiano discussed earlier: rather than being metaphorical, the film’s use of Polaroids is literal. For Shelby, memories do not just look like Polaroids: they are Polaroids. As Shelby says at one point in the film, ‘The world doesn’t just disappear when you close your eyes, does it? Anyway, maybe I’ll take a photograph to remind myself.’

Ultimately, we approach the photography of our own lives with an extended, less paranoid rendition of Shelby’s mania. Whereas his are taken for the most basic of purposes – remembering his wife has been killed, who he can and cannot trust, the car he is looking for – ours are taken with a more general ambition: creating banal mementos. It is just that the act of forgetting and subsequently remembering takes place over a more natural period of time.

We fill our lives with souvenirs, or at least we did before things became digitised, precisely because of a need not all that different from Shelby’s: to recall, to recollect, to remember. As Annie Ernaux mentioned earlier, all of these actions are far from devoid of real interaction but often express a deep desire to travel back and embody the person and space from those moments.

The person we were is always a potential project for betterment in hindsight.

Of people held in Polaroid cages, I can see their dead eyes blacken with anger at being forgotten, the already grainy pupils draining of colour into sepia malice as each photo is put in a box or left in a charity shop. Their anger is palpable. I can feel it fizzing in each photo, overtaking the genuine emotions caught by the camera in the moment, replaced instead by the desperate rage to be remembered.

Even the perfect souvenir, the perfect memento, is forgotten in the end.

Time Regained

I have never been impressed with a single Polaroid I have taken. At most, I have been satisfied. Considering this made me wonder about photographs that have truly left me awe-struck and if I could remember an occasion when I was left speechless and deeply moved by a Polaroid taken by someone else.

Most of the Polaroids that fill this book have my admiration, curiosity and respect. Few have my absolute faith.

I recall seeing some of Walker Evans’ Polaroids and being touched by their melancholy. I remember staring at one for a while when on a computer in a damp-smelling segment of a university library one winter in Liverpool and being powerfully transported into its dilapidated realm of Americana. But again, it verged more on impressive than that rare sense of the transcendent, that feeling that only a handful of works in our lifetime ever achieves.

I strongly believe that writers looking into anything should have had this reaction to a piece of work before daring to write appreciatively about it. Luckily, I have had this experience with a handful of Polaroids; all taken by the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky.

Tarkovsky was born in the village of Zavrazhye, the son of acclaimed poet Arseney Tarkovsky. Andrei was always set to be an artist with a poetic gaze. Few could have predicted the heights he would reach in his handful of films, beginning in earnest with Ivan’s Childhood in 1962 and concluding with The Sacrifice in 1986. His seven feature films are the closest the cinematic medium has got to expressing the theological transcendent, doused in faith, memory and time.

Watching his 1979 film Stalker, adapted from the novel Roadside Picnic (1972) by the Strugatsky Brothers, is the closest I have ever come to experiencing a theological moment through art. Such was the emotion in seeing it that the work of the filmmaker has haunted me ever since. His sculptures in time – to play on his own terminology, from his beautiful book Sculpting in Time (1984), for how he saw the making of cinema – defy earthly explanation, such is their inexpressible beauty. With this in mind, for an artist interested in the most theological expressions of emotion and memory, it is surprising to find that Tarkovsky also worked in Polaroid photography. Just like his films, his Polaroid images left me in a state of grace.

Tarkovsky worshipped at the altar of memory. His films are replete with attempts to portray the power of his own, especially those from of his rural childhood. The beautiful aesthetic of his films help relate such memories even when fantastical, as in his adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris (1972); where a planet conjures a physical being from the memory of a character.

Tarkovsky’s relationship to Polaroids feels similar to the lead character Kelvin’s relationship (played by Donatas Banionis) with his own memory and with his dead wife Harri (Natalya Bondarchuk); brought back to life on the space station orbiting the strange world of Solaris.

At first, he cannot comprehend how his wife can be there, their meeting opening the old scars of his grief, initially manifesting at anger. How closed his memories were before travelling to the station and meeting the ghostly recreation of his wife. More poignant is the ending of Solaris which is initially seen to be Kelvin’s return home to the house of his parents on Earth. A visit to this house opens the film. There is only one problem on this second visit: it appears to be raining inside the house rather than outside.

The planet has recreated the memories of his childhood home with a few mistakes, and the scientist has either been tricked into believing he is back or, more pessimistically, has been so trapped in nostalgia thanks to Harri’s ghost, that he has chosen to live in the purgatory of a misremembered home rather than face the loneliness of reality.

I wonder how many of us would ultimately choose the childhood home, where it rained indoors.

Several elements come into play in Tarkovsky’s Polaroids. The first is that, in spite of still being young, Tarkovsky technically turned to Polaroids in the final years of his life, though he was not initially to know this.

Working on Stalker had been a great strain on everyone involved due to shooting it twice thanks to using an unworkable batch of film stock. Under normal circumstances this would have destroyed a film project, especially one that was made by such a technical perfectionist as Tarkovsky. Instead, they reshot the whole film with the director using money he was supposed to use on a new film. The problem with this extended filming was one that crossed from the world of the film into reality. The so-called Zone of the film – an area cordoned off by the government due to something landing there that has strange powers – was genuinely a dangerous area; an eerie place that had incredibly detrimental effects on the crew, including the director.

The film was shot in Estonia near several chemical plants, the dangerous outflow of which entered the waters seen in the film. It is time spent in this place that is often attributed to Tarkovsky’s death from bronchial cancer only a few years later at the age of 54. Many of the crew members became incredibly ill after the film, and Stalker’s resonance has often been contextualised through the disintegration of the health of those who made it as much as the characters’ moral journey in search of The Room at the heart of The Zone; a place that houses anyone’s deepest desires. It was a film where everyone gave everything to get it done, even their lives.

The other aspect in Tarkovsky’s Polaroids is nostalgia for a home, a sense of trying to recreate the world he loved in Polaroids after it was forcibly taken away from him by the Soviet Union. Tarkovsky’s relationship with the Soviet Union had often been strained, with multiple efforts made to disrupt much of his filmmaking. The authorities certainly detected a certain ambivalence towards the Soviet project in several of his films.

By the time Stalker existed, it was clear that Tarkovsky had to leave his home country if he wanted to continue working, not least because of the political pressure put upon him. Such was this pressure that he was even forced to leave his son in his homeland while he moved between several European countries, in particular Italy and Sweden where he made his final two films, Nostalghia (1983) and The Sacrifice.

Even if this had not been the case, Tarkovsky was still preoccupied with his own personal memories, especially realised in the stunning Mirror (1975). His films were attempts at a recreation of sorts, traversing back to those impressions ingrained from our childhood in us all.

The results of all of this are still, for me, the most beautiful photographs ever taken using a Polaroid camera. Every ordinary object is rendered in the presence of the holy.

Tarkovsky’s earliest use of Polaroid photography appears to be in the years when he was preparing for Stalker, around 1977 as most scholars believe, the camera gifted to him by the director Michelangelo Antonioni. That director’s legacy for photography extends far beyond its use in Blowup.

Tarkovsky had no prior interest in photography, and was much more concerned with virtually every other art form, from classical music to Renaissance painting. His son Andrei recalls the surprise with which his father turned to such a popular, everyday medium. ‘I don’t remember him having any interest in analogue photography,’ he said, ‘I’ve never heard him talk about photography… But he liked Polaroids a lot for their immediacy, for the possibility of seeing the result immediately.’

Essentially, his son attributes the presence of the Polaroid as the key factor in Tarkovsky’s desire to use it. Equally, his proficiency with the camera came from his ability to limit the inbuilt parallax defect, resulting in atmospheric colours and detail.

On one of the last visits to his household before his exile and death, Tarkovsky was armed with his Polaroid 600. His son attributes the atmosphere of the photos to a premonition of the finality of his visit. Tarkovsky was not merely documenting his homeland because he was losing it but also because he was in the process of recreating it for his film Nostalghia.

With this in mind, and considering the level of detail which the director insisted upon, it is difficult to distinguish between the real-life journey to the house and his recreations of it in a small Umbrian town near the Tiber, both documented by the director in Polaroids. In fact, the film’s designer Andrea Crisanti was given the Polaroids of the original building to work from and, notoriously, when Tarkovsky was unhappy with the angle of the house, rather than moving his film cameras, the whole building was moved to fit the exact angle portrayed in his Polaroid.

The Polaroids are the link between his life and his films, his homeland and the land of his exile. It makes them difficult to discuss with exactitude, but this is appropriate for an artist whose work is about the unspeakable. As Tarkovsky junior suggests of his father’s Polaroids, ‘It was very accurate, very attentive to details and the sacredness of memory.’

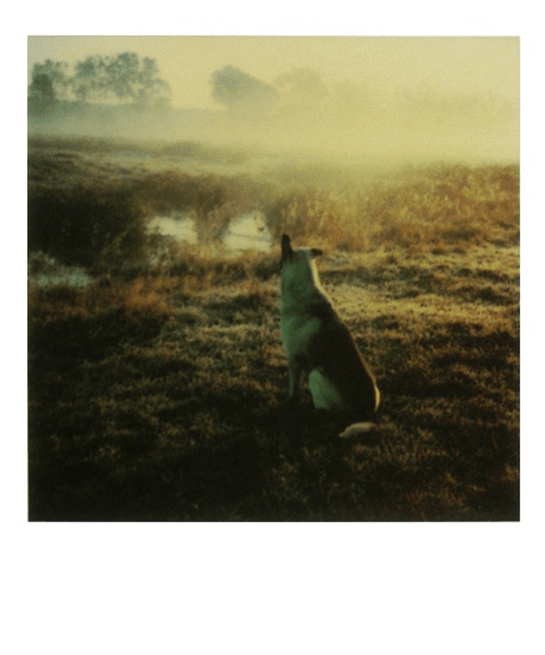

The Polaroid above was the first that I saw by Tarkovsky, and I was lost in its sacred memories straight away. I recall my hands going cold as if the mist that the dog in the image stares through was seeping out of the photograph and into my room. The colours were the colours of memory.

Tarkovsky is the artist who realises more than most Modiano’s claim to memory’s Polaroid likeness. The mist looks to be sweeping away the landscape, as if the land is literally vanishing before the photographer; the homeland fading into the beyond on his last visit.

Alsatian dogs are present in many of Tarkovsky’s films, seeming a talisman of memory and comfort; loyal support for the lonely. I feel this to be an autobiographical element in Tarkovsky’s films, even when they appear in more overtly fictional narratives such as Stalker. The so-called Stalker of that film is also accompanied by an Alsatian that seems to guard him from worries, though his worries are the strange alien powers of The Zone rather than the very real political powers of the Soviet Union. Tarkovsky enjoyed taking photos of his dogs but there is something profound about them; the sheer pleasure of their company overwhelmingly there. They are far from the casual Polaroids often seen of pets.

Arguably, the main reason Tarkovsky began his Polaroid photography was research, coupled with a desire for physical mementos of his soon-to-be-lost homeland. His trip back before his exile was to document the buildings and landscapes of his home so he could recreate it exactly in Italy. The photos are haunted by the longing of someone about to lose all they have known, and his final two film projects are attempts to regain what is lost.

Tarkovsky’s photos are best seen under one particular guise: that of losing a home. We all take photographs with this intention on some level, so Tarkovsky’s Polaroids still seem everyday and easily understandable as they express something everyone can feel kinship with. This is in contrary to John Berger who believed the synonymous relationship between photographic film and memory was meaningless. ‘That is a banal simile’, he wrote. Yet Tarkovsky’s expert skill makes his Polaroids more than just sad snaps of the lost home: they feel like physical renditions of memories. They are more than a simile.

Another aspect that Tarkovsky explicitly links to memory is light. Take the beautiful Polaroid above as an example. The photo is lit from the window, suggesting that the flash of the Polaroid has been disabled. The table is in the middle of being used, in spite of the darkness of the moment; littered with objects that suggest the preparation of a meal. The moment feels uninterrupted, far more than other Polaroid photos, because of the light; the harsh flash would imply a pause in the happening. The natural light of the window, on the contrary, implies a casual reflection on the moment, albeit ironically as it no doubt took some effort and mastery to achieve this effect in camera.

When I recall my memories, even if lacking the picturesque aspect achieved here due to the mass-produced objects on show around me, I see them in these colours. They verge on a colourful cousin to sepia, where they have certainly aged but not lost any vitality. They have simply matured and grown like trees.

Tarkovsky’s Polaroids and films are replete with these colours and lighting. It is a remarkable achievement of shade and tone, where the Polaroid can age but not fall into the disintegrating blue of time. If general Polaroids age with the same disintegration as our own real memories, itself providing an emotional resonance, Tarkovsky’s confidently live on, determined to challenge disappearance.

The most ardent characteristic in Tarkovsky’s Polaroids is homesickness. His choice of subjects, his desire to catch things in the merest presence of light; it is all so fleeting, as if he is in search of consolation as to the delicate nature of the things we love. He cannot stare too long and in too bright a light as this will provide confirmation of the loss that already drove him to photograph such things in the first place.

Best to leave those loved, cherished moments and pasts in half-shadow, lit by memory rather than reality.

These are the Polaroids of a man totally aware of what he is losing. The memories enclosed are all the more astounding because of how casual his use of the camera appears. Production snaps, photos of his various abodes, a few behind-the-scenes shots for Nostalghia and The Sacrifice; the sort of things that are, by their nature, perfunctory and yet achieve something transcendental when under a homesick eye. It colours his entire output of Polaroids as well as his final two films. They are quiet and trembling with what words left unsaid. As one character from Nostalghia puts it, ‘Feelings unspoken are unforgettable.’ This summarises his Polaroids with precision. Tarkovsky is expressing without words, just as he often did in his films, the torment of time and all that it takes from us.

I often think back to Tarkovsky’s home, the real and the imagined; that modest shack outside of Moscow. This is chiefly because the role it plays in the final scene of Nostalghia renders it one of the most poignant and heart-breaking moments in cinema. Comparisons between the Polaroid of said house and its role in the film are intriguing to say the least.

The one Polaroid I can find of the house is enjoyably ambiguous. It could be the actual house or one of the fake houses built for the film in Italy. The ageing suggests that it most likely is the original as Tarkovsky’s Italian Polaroids have a richer, more varied colour range. This is one of the few images by Tarkovsky properly faded into hazy blue; the most delicate and treasured of his memories. It appears to have been exposed to the light of the world more than his other photographs.

The landscape is fading into mist and memory, with a horse seen just outside the building and an ambiguous figure walking towards it. The light is on the verge of blinding, as if this was the final memory of the photographer. Considering the scene it would eventually inspire, it is not unreasonable to assume that the director’s final memory, before being taken from this world, would have been of this view.

In the final scene of Nostalghia, the main character (a likeness for Tarkovsky) attempts to place a candle on a wall, walking from one end of a drained, steaming spa to the other and starting over again when the candle continually extinguishes. When he finally completes his challenge, he dies in the spa with the candle flickering. Then we are transported somewhere else, into a sepia afterlife.

At first, the writer appears to be sat outside his childhood house. He has a trusting Alsatian lying mournfully beside him and a pool of water reflecting the scene like a mirror. The camera slowly tracks back, revealing that the house is now supplanted into the ruins of a cathedral, one he visited earlier in the film. In death, the poet turned to the holiest of memories, and that was of his childhood home, the one that was taken away and denied to him in his final years.

Snow begins to fall and the camera finally stops to take in the view; the shack that seemed so humble now housed in the monumental carcass of another theology. A dedication to Tarkovsky’s mother fades onto the screen and thus ends the most powerful ending in cinema.

In both Polaroid photography and film, Tarkovsky placed the house of his childhood in a holy realm. The Polaroid was just as effective a setting as the crumbling, beautiful ruins of a cathedral to venerate this most treasured of memories.

The memory of Polaroids has never seemed so sacred.

Hi Adam, I am a long time fan of this blog (and a Tarkowsky fan) maybe off topic but after losing my Dad a couple of years ago, I developed an odd Hauntological habit. As a child I remember whenever an advert appeared on tv I would stop whatever I was playing and watch enraptured. Most were just loud garish selling spots but some stuck in my mind maybe the music, lighting of voiceover but some bring back pangs of nostalgia. Namely the esso adverts with the tiger, castrol gtx with its melancholy trumpet or the Turkish delight advert with its soft focus. You tube has revealed these to me again. Some late Friday nights are spent watching these again. Some not exactly as I remember but it has proved cathartic after my Father’s passing.

Drew Hartill