In 1859, the Harvard poet and medical professor Oliver Wendell Holmes described photography in a much earlier guise as being a ‘mirror with a memory.’ One aspect lost in this oft-quoted soundbite by the noted medical reformer was that he was discussing photography as explicitly producing an object.

It is the photograph that is the mirror because the viewer can look and see their likeness to some degree. The photograph is the object containing the memory rather than the camera. Physicality is the essential quality that gifts the Polaroid with its unusual and curious relationship to time. It ages with us like a faithful companion, right up until the moment when it is all that is left of us. The fact of their continued existence after we are gone feels melancholy because we can hold all that remains of the photographer, in our hands like an urn of personal experience. This is certainly what I felt when looking through the Polaroids that I found in the envelope in Strasbourg.

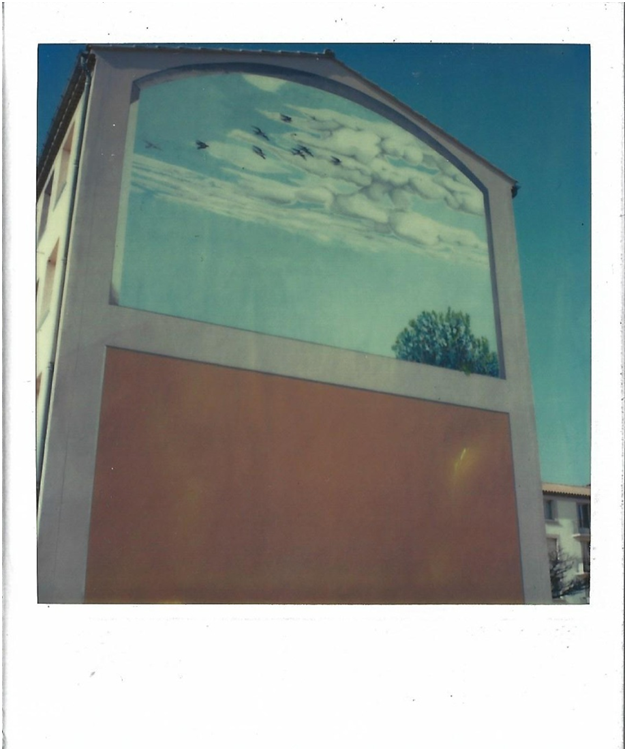

Another beautiful photo from the envelope is the one above. Time is engrained into this photo due to the ageing process as much as anything else. I love this strange Polaroid, not least for the unusual building and its artwork which portrays a blue sky pockmarked by a flock of ducks. The fading of the blues has resulted in the mural resembling a giant window onto the sky above. For me, the banality of this photograph highlights a quiet optimism in a way that I cannot quite explain.

In Gordon Burns’ novel Alma Cogan (1991), the book’s narrator suggests that photographs are really messages to our future selves, happy ones that tell us to cheer up and remember better times. ‘I was told to think of a photograph as being a message from myself in the present to my future self,’ Cogan recalls, ‘saying “I was happy”.’ In her case, the opposite occurs as her stardom, as evidenced by photographs of the singer, masks the quiet frustrations of her personal life. The images from the envelope, however, do indeed resemble a humble message to the photographer’s future self, one relating a time when worries were likely beyond the horizon.

Worried people do not photograph walls.

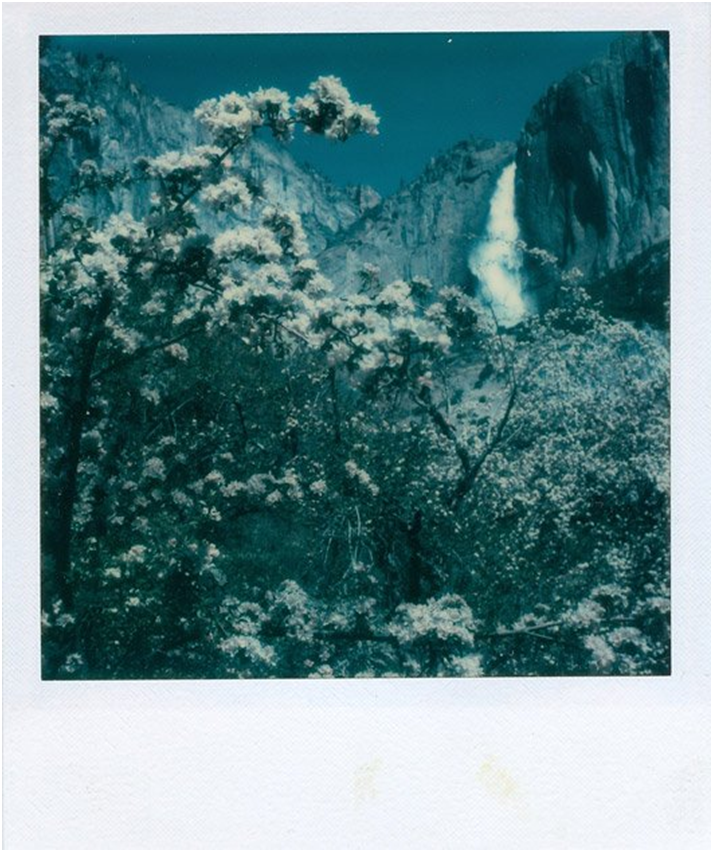

Another interesting thing about this particular Polaroid is that it reminded of how there is little difference between great photos taken by ordinary people and those taken by respected photographers. The aesthetic is an obvious equaliser. Polaroids by ordinary people feel profound, while Polaroids by photographers feel personal and intimate, atypical to more dominant traits in professional artistic practice. Take then, for example, the Polaroid below by Ansel Adams. Already, in comparison it the anonymous Polaroid, there are likenesses which are surprising to acknowledge in spite of the obvious difference in subject.

Adams had an intriguing relationship to the Polaroid camera, though it was not by any means his dominant interest. Unlike Walker Evans, who turned to the camera in older age, Adams was an early adopter of the form. The photographer appeared in an advert for Polaroid in 1950 in an issue of the magazine The Camera. He endorsed the machine, though it is worth noting that the camera in this iteration was incredibly expensive; more of an affluent novelty.

Adams is quoted in the advert for the camera proudly enthusing that ‘there’s no thrill like seeing your pictures on the spot at the very moment they mean the most, while everyone is there to share the fun.’ Whether this is sales spiel or Adams’ genuine belief is debatable, but something is undeniable here: the charge of the Polaroid comes in making memories instantly, when they mean the most. The act of looking at the photos is part and parcel with the memory that it captures.

Adams played a key role in landscape photography, especially seen through an environmental lens, but predominantly canonised photography as a respected art form through his various tangential activities; founding a range of societies, developing several photographic techniques, and playing a pivotal role as advisor in the foundation of the Museum of Modern Art’s photographic department.

For someone whose role was so essential in the shift in pubic respect for all photographic media, it is refreshing to find such an influential figure not forgetting the humble Polaroid. There is a practical reason for this in that Adams was personal friends with the Polaroid’s creator Edward Land and actually worked on the very development of the format. Wandering out into his most beloved landscape, the Yosemite Valley, he was the perfect photographer to conduct field tests in the format.

For Adams, the Polaroid was another tool that allowed photography to be a more social affair, in spite of his many tests and noted Polaroid photographs being solitary; not taken for hindsight in the far future but for the moment. In spite of this, the use of the Polaroid in Adams’ photography does have a melancholy tinge today, arguably for parallel reasons to that found in the anonymous Polaroids.

In the image taken in 1979 of the Yosemite Falls, littered with exploding blossom drowning in blue time, the likeness between such a successful photographer like Adams and an unknown one is found in the fading of the image. The landscape may be dramatically different and probably more typically beautiful if we are being honest. Yet, time has rendered them closer together because the sunlight they shared was the same.

The past turns Polaroids blue in colour and mood. Places witness a slow azure fog arriving, filling the air and turning even sunny vistas into frosty memories. One photo may be of a lowly holiday resort while the other portrays one of the great natural wonders of the Californian landscape, but the Polaroid renders them equally finite and subject to change, as if their worlds are made of disappearing ice.

Landscapes and architecture are given a wash of delphinium, yet that colour is not a filter applied for some hollow reason; this is the photographic equivalent of wrinkles on skin.

Polaroids from the past containing people, famous or unknown, possess a different flavour; a gaze which is sometimes difficult to meet. Part of this comes from knowing that people in older photos are likely dead; ghosts staring from their frozen moment. The photographs become ghostly as they look out from their epoch into ours.

Any number of Polaroids could be used to discuss the effects of the medium on people as subjects, but I find that it takes a hold most firmly in Polaroids of happy occasions, in particular birthdays and weddings. In reality, such events often set my teeth on edge with trepidation at the likely forced socialites and my own particularly bad memories of such occasions.

Photos of occasions never really look happy. I find this pleasing as I hate that sort of thing. Before the days of endless digital retakes of happy moments – cake-cutting, vows, blowing out candles, all of the usual horrors – the element of analogue chance brought a refreshing truth to events so often mythologised. For every celebratory digital photograph of a gushing bride and nervous birthday boy, there are likely dozens of takes left on the hard-drive detailing a mixed range of emotions that naturally bubble up during such events; edited out and hidden shamefully away.

When looking at analogue photos, the chances are that the moment captured is more likely one of these unfortunate slips into the truth of the scene, captured for posterity like an admission of stony guilt. In analogue photos, especially those as finite as an 8-shot pack of Polaroid images, realisation of the change being celebrated in all of these events is more often seen. Change is horrifying, even if we are glad in hindsight. In the moment, however, I think our bodies tell the truth.

I came across a post online not long ago that had gathered an array of Polaroids from various weddings, most of which were taken in the 1970s and 1980s. The photos are filled with gaudy meringue dresses, dangerously sentient facial hair and eyes that suggest awaiting the gallows rather than the aisle. The effect of seeing these Polaroids is strange because the occasion of their taking is, on the face of it, important. Therefore, their existence on the site suggests we are dealing with a collection of moments that the original owners either are no longer around to remember or, more likely, best want to forget.

Ignoring the enjoyable period trappings for a moment, these Polaroids have gained a patina of pessimism, the colours fading like Adams’ landscapes and my anonymous holiday snaps. The relationships likely faded with as much, perhaps more, temerity as the Polaroids themselves.

A Polaroid of a wedding is daring the marriage to outlast it. The odds are against it.

I love how the misty, purplish colours render everything sickly yet bland. They possess a mixture of the garish and the empty. Every action looks conscious. I wonder what the couples in these photos thought when they saw or held them. Did the photographer laugh at the image when sat at one of the tables merry between proud relatives? Did the photographer show the couple his omen or hide it out of fear that it made them look totally agonised? Did the couple, or perhaps just one of them, look at the photo again after it had ceased to have any meaning and wonder what the point of it all was? And did the image bring back the memories of the sounds, sights and smells of that moment? I imagine it being akin to cursed Madeleine, the senses it rekindles being distasteful.

‘What was I thinking?’ they cry.

Every single person in the Polaroid above is watching the father and the bride. They appear more like a congregation of mourners or spectators watching someone being escorted to the chair. One man almost has his head bent in respect for the soon-to-be departed. It is a reading enhanced by the faces of the bride and father. The lack of opportunity to take other photos quickly, as we have in the digital today, means that the photo of this happy moment resembles nothing less than a ritualistic execution.

Photographic subjects such as these were designed to be looked at in remembrance. We are aware of this potential hindsight more than ever today. It manifests in our obsessive need to document everything, as if every instant is either worth preserving or may slip from us if we are not careful. With Polaroid photography today, more kitsch expressions of this need are fulfilled.

I recall the very last wedding I subjected myself. I survived thanks only to an open bar and the thievery of several large blocks of expensive brie that I sat eating alone in a toilet cubicle as the groom was loudly sick into nearby a sink. The family had arranged for a full team of pricy digital photographers, each with at least two cameras hanging from their necks, to be deployed at great expense; moving around the day and capturing every instant. No stone was left unturned by these photographers, who displayed a war-photographer dedication to making sure even the wedding’s most awful, shameful moments (such as my stealing of the brie) were captured for the future enjoyment of the happy couple. But there was one other officialphotographer there for the event: the attending crowd.

Of course, this being the mid-2010s, when camera phones were normalised but still quite awful, this would have been the case anyway as a whole variety of adoring relatives and friends made sure we would have excess documentation of the costly event from all angles, even those obscured by the wood-beam design of the chapel and blurred by the clumsy movements of drunken family members after an hour or two of abusing the open bar. But the happy couple wanted something more than this: they wanted Polaroids.

Sat on a table rather ominously was a large book, similar to a book of condolences. It was filled with Polaroid-sized spaces, a small square for written messages, and an awful cover that looked like wallpaper from the turn of the millennium. Next to this was a vintage Polaroid camera, the model of which I cannot recall as I was drunk off Johnny Walker Black and brie, alongside several piles of stock. Attendees were encouraged to use the Polaroid to take photos of each other and place them in the book so that memories could be preserved. Quite why the photographs taken by the expensive army of digital photographers were not adequate enough was puzzling, that is until the reality hits home that photos that are physically there carry more charge, especially when taken by friends and relatives.

I recall very little about the photos that gradually filled this booklet over the course of the day, though the messages left were largely nonsensical and filtered through hours of drinking and celebrating. I do recall my contribution, taken much later on and influenced strongly by spirits. It was an image of my new shoes which I remember being particularly taken with. Dizzily slotting the photo into the booklet, I scrawled underneath, ‘My excellent shoes’ and meandered off in search of more brie, satisfied that even this innocuous inclusion would somehow play into future reminiscences.

‘Do you remember the Polaroid of the shoes next to your mother?’ I can hear older versions of the married couple saying in the years to come, debating which idiot took it. I can imagine, equally, the images that really did accompany the Polaroid of my shoes; overly lit faces trying to look happy but likely looking tired and blurred by booze.

Search online and an array of similar photo-books appear on offer, some for absurd amounts of money, replacing the traditional books for such events. They are in abundance and are almost uniquely diabolical in design. But more importantly, they are sold as being a potential for any number of different events. Anything that you want to remember in extra emotional detail? Deploy a Polaroid camera, some stock and one of these books for authentic links between then and now.

I sometimes wonder what we are really asking of ourselves when we take a Polaroid. It feels both a post-it note reminding us to pick something up from the shops and a time-capsule buried and designed with the excitement and happiness of a future self in mind; the sort that used to litter the Blue Peter garden.

Assumed hindsight embodies the act of taking such photographs.

The writer Annie Ernaux came upon this presence when looking at photographs of her younger self, noting how physical time grows between the body’s changes and the earlier photos documenting it. ‘I am a ghost,’ she writes, ‘I inhabit her vanished being.’ She, too, was looking at physical photographs of herself, trying to understand the person she was, and attempting to bridge the differences, physically and mentally.

Interestingly she does not consider this an act of remembering but one of embodiment. ‘I am not trying to remember:’ she argues, ‘I am trying to be inside this cubicle in the girl’s dorm, taking a photo. To be there at that very instant, without spilling over into the before or after.’ She exemplifies the opposite to what so many theorists claims happen when we take photographs and look at them. But she also captures what physical photos often casually achieve; placing the viewers into those earlier scenarios and mindsets, hence why memorable events such as weddings are prime candidates for Polaroid subjects, brie or no brie.

Part 10 coming soon.

So interesting and thought-provoking! Thank you.

Thank you!