This interview was originally was published on the Small Cinema Liverpool website with thanks to Sam Meech and the BFI. However, since the closure and destruction of the cinema by Liverpool developers, the website has since been closed. This interview is saved here for posterity and in appreciation of a much underrated editor, filmmaker and artist

Celluloid Wicker Man: In terms of filmmaking, how did you first make the break into the industry and what links did this have with the Free Cinema movement?

David Gladwell: While at school, I had made a 9.5mm film using my father’s camera which he had used for home movies for recording the likes of the first days I walked and the occasion of my third birthday. This gave me the taste and then, by the time I was at Art School in Gloucester and with a photographer friend who owned a 16mm camera, I had made (the short films) A Summer Discord and Miss Thompson Goes Shopping.

After that, during a year in London, heading somewhat reluctantly towards a career in teaching art, I made contact with the British Film Institute. There, to my surprise, some interest was shown in the ‘Miss Thompson’ film – most significantly, by Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and others who were working in Soho basement cutting-rooms on their 35mm Free Cinema productions, Every Day Except Christmas, We Are The Lambeth Boys, etc. This was my first experience of the professional scene when I was able to watch the editing process.

I was even asked for my opinion on whether I agreed that this or that picture frame was a suitably ‘valid image’! Based on their viewing of my little 16mm film, I was recommended to Basil Wright, the famous director of the highly rated documentary, Song of Ceylon. Over a beer in a Soho pub, Basil Wright asked if I understood how lucky I was that he was taking enough interest in me to recommend me on to the head of production at British Transport Films, Edgar Anstey. I understood absolutely of course. This eventually resulted in my being taken on at BT as a Trainee Editing Assistant. One of the first productions I worked on there was John Schlesinger’s documentary about Waterloo station, Terminus, which was a great introduction.

CWM: The BFI Experimental Film Fund helped make your short Untitled film in 1964. How did this come about? What were the ideas behind it?

DG: My previous contact with the BFI and their appreciation of ‘Miss Thompson’ meant that I was in a good position to be in the running for a financial grant when their ‘Experimental Film Fund’ came into being. I had always, since an early Film Society viewing of Jean Vigo’s Zéro de Conduite, been fascinated by the visual possibilities of slow-motion filming; and my 10-minute An Untitled Film for the BFI was 100% slow-motion – as slow as it was possible to get a camera to go in those days (although the technique is so easily achieved these days). The depiction of a violent act seemed to me an obvious subject to explore in slow-motion and I was grateful for the opportunity to do so as an ‘experiment’ for the BFI.

By then, I had become a freelance, working as an Editor on an assortment of documentaries, increasingly for television; often arts documentaries and occasionally dramas. One could say that ‘the rest is history’ although, I suppose, history of a sort had already been happening. Along the way, directing had always featured intermittently in my career, though I have always found it difficult. As an Editor, one is presented with the already shot film material – and required to make something of it. In doing so, one is able continually to work and rework material until, eventually, a satisfactory final result can be achieved. When directing, you do not get that multiplicity of chances for trial and error – and I find it fraught with anxiety.

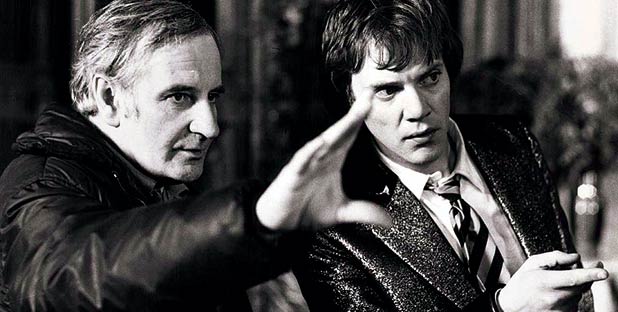

CWM: You began a very successful working relationship editing Lindsay Anderson’s films If…. (1968) and “O‘ Lucky Man!” (1973). How did this occur?

DG: Lindsay Anderson came back into my life when I heard that he was looking for an editor for what would be his second feature film, If…. An interview with him surprisingly resulted in my being offered the job.

CWM: Do you have any particular fond memories of working on these films?

DG: Working on If… for six months and then on ‘O Lucky Man!’ for a year were significant and, on the whole, enjoyable periods of my career, during which I learned much – not least about the pros and cons of the personal relationships which go on during the creative process. Lindsay, however, had warned me that he was thought to be a difficult task-master.

CWM: Requiem For A Village (1976) was made after working with Anderson. How did this film come about and what was the reception like for it?

DG: Requiem for a Village was also sponsored by the BFI; the Experimental Film Fund having evolved into their Production Board. Over a long period previously, which included two years of National Service, I had harboured the wish to try and incorporate some ideas of the English artist, Stanley Spencer, and his paintings of a churchyard resurrection in which previous generations of villagers are united with the present; and when I came across the documentary books of George Ewart Evans, The Pattern Under the Plough and Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay for example, I realised I had found a way of depicting the subjects which could represent those previous generations. Ewart Evans had interviewed and recorded rural testimonies, memories of the past: crafts people and people whose daily lives involved horses, the power source of the countryside.

CWM: Requiem For A Village is an unnerving evocation of certain forms of rural life. How does the rural environment and ways of life fit into your work?

DG: The film was made with the surprisingly enthusiastic help of amateur performers across a wide area of the county of Suffolk. It was here that I was able to find the required still-existing examples of old rural crafts such as smithing, wheelwrighting, horse-ploughing etc. My previous experience of editing proved to be invaluable in the completion of the film as it was this aspect which was instrumental in bringing together the many disparate elements which had been filmed across the county.

CWM: After Requiem For A Village, your next feature, Memoirs Of A Survivor (1981), was dramatically different in that it was distinctly urban and dystopian. Was this a deliberate move away from the rural in order to reflect the changes brought about in the 1980s or merely a necessity because of the narrative of Doris Lessing’s original story?

DG: Requiem For A Village was shown at the London Film Festival of 1975 and led eventually to the possibility of my making a feature film of Doris Lessing’s novel. It was probably the fragmentary quality of this story which attracted me – including, again, the bringing together of different worlds.

More on David Gladwell’s Work: