One of Derek Jarman’s first short super-8 film was the haunting A Journey to Avebury. Early evidence that Jarman was interested in the genii loci of English landscapes, his walk through the Wiltshire landscape, after the intense stint of work on the sets for Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971), had a larger influence upon him than the singular short film belies.

The ancient landscape generated a whole range minimalist paintings by Jarman, very much in the abstract tradition of Paul Nash and others, as well as the more famed short film (arguably famed for its posthumously applied soundtrack by cult musicians Coil as well as for its social media friendly esoteric imagery, now very much in vogue). Jarman has always been a quiet landscapist as well as the gay pagan punk that the gallery likes to characterise him as.

Having painted landscapes since leaving school, it could be said that this silent creeping of landscape into Jarman’s work, later manifesting in the full blown garden at Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, stems from his earlier exploration of the landscapes of Avebury. He seems to have been possessed for a time by the fields and stones of the little village.

A Journey to Avebury is sometimes treated as the overall output of this dreamy summer period but Jarman produced roughly a painting a year of Avebury during the early years of the 1970s, recreating the same landscape while experimenting with the area’s natural and manmade landforms through colour and line.

Jarman had toyed with simplifying landscapes in painting in the years before he even picked up a super-8 camera.

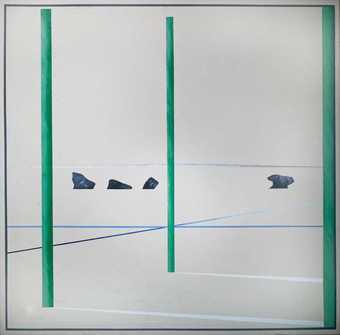

In paintings such as Landscape with a blue pool (1967), Landscape and Landscape II (years unknown, though undoubtedly between 1967 and 1970), Jarman reduced landscapes to a blank colour – either the colour of the canvas itself as in the latter two or painting it one flat colour as in the former – and filled it with abstract landforms; horizontal lines creating the perspective of distance and the gradient of the land.

These were then contrasted with occasional, more overt presences such as the blue pool and rocks in Landscape with a blue pool or a ritualised person seemingly sat under a totem in Landscape II. He referred to these as ‘eye-tricking imagery’. The latter is especially interesting in that the vertical lines feel like totemic objects rather than trees or other such natural features. They are paintings fluent in esoteric.

Jarman was clearly interested in re-mythologizing such landscapes, finding quiet power in the typical English vista. It is no wonder he felt such a connection to Avebury when he eventually visited.

In the Avebury series of paintings, Jarman uses the same technique to form landscapes but is reacting to a more overtly enchanted place. The natural obtrusion of Avebury’s many menhir fits Jarman’s minimal form, ironically mimicking their real relationship to the eye; their strangeness in the landscape renders the fields around them as blank in comparison. The grass is Avebury’s canvas and not its main feature.

In these paintings, totemic poles cast their shadows on the canvas grass, accompanied by a variety of stones sitting upon planes created by horizontal lines. In a sense, Jarman does not present the landscape as it is but in abstraction; bunching up West Kennet Avenue and the like into a neat projection.

With the stones placed at random in the paintings, it would not be surprising to find these stones taken as models from his super-8 footage. He certainly did not paint them in situ. In A Journey to Avebury, many shots consist solely of one stone, mostly taken around the main ring of the village. Avebury Series No. 2 and No. 4 (1973) have a sense of these objects being lifted from the landscape and realigned, collage-fashion, in a memory-scape of Jarman’s own making.

Like A Journey to Avebury, the series feels like a false memory of the place. It is a fragmented, imagined Avebury. These are the bare bones of the place stained on Jarman’s retina, retained in the mind and then reassembled. It is the equivalent of an incredibly neat and tidy scrap-book; something that Jarman would make more earnestly about his garden in Dungeness, later published variously as coffee-table-friendly books.

Interestingly, the painting Jarman put most of the Avebury menhir into is not officially part of the series but instead a 1973 painting called Sand Base. The fact that it is painted in the same style and in the same year as Avebury Series No.4 suggests that it is still part of the same general movement of work even if not officially. But there is something different about the stones in this work.

Whereas the stones in previous paintings generally have the same texture, the stones here are split into two forms. One lead stone is full of detail like the leader of a cult, while the other follower stones are painted an oily black. Some stones on the painting even feel observed with a bird’s eye view, the black rocks only defined by the shadows they cast upon the ground. But there is an undeniable sense of a community created through a hierarchy of stone, as if we are witness to some ceremony that human eyes were not meant to see as the sun dipped under the horizon.

Wow! Beautiful paintings. I haven’t seen this kind of painting before. Art is certainly about being creative. I love landscape painting too and I’ll start soon and share my progress here.

He was an incredible fine artist as well? Had no idea.