Journeying

Maps

A Polaroid is a map of sorts. It covers such a small personal realm within its cartography that the only area it helps to locate is arguably beyond the physical world and within the memory.

It shows the way back to the spaces of our past.

The image of a Polaroid may fade in comparison to our experiences but it is still a part of them. The author M. John Harrisons explored this idea in his 1989 novel Climbers. The narrator of the novel spends his time climbing rocky plains, while also quietly indulging his habit of taking Polaroids. Polaroids acted as ‘if pigments could learn about what they represent, events understand themselves more accurately towards the end than the beginning’. Harrison’s description is apt considering that a Polaroid’s life arguably begins at the point most other photograph’s rarely reach today.

Considering a Polaroid as a miniature world brings to mind the surreal potential of a 1:1 map, a dizzying idea that I first stumbled across in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story On Exactitude in Science (1946). In the paragraph-length short, Borges interrogates the strange drive we have towards perfecting likenesses; so much so that they slot back into the reality they depict (rendering them useless as a mere likeness ironically).

Perhaps this desire belies our general predilection towards control: we can remake the world if we wish and in our own design. ‘In that Empire,’ Borges wrote, ‘the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province.’

The insinuation is that under the world sits its own great map. Walking in a desert, the sand could blow away to reveal the tattered remains of the 1:1 map underneath, smothering the world like a membrane. In my mind’s eye, it possesses an aesthetic akin to a damp cloth draped over a choking face. Appropriately, we are a society drowning under a mass of smaller likenesses though, thankfully, they mostly remain on screens.

The Polaroid highlights two things in relation to Borges’ beautiful story, though obviously a Polaroid cannot contain the whole world literally (yet it can contain, for a brief instant, your whole world). The first is that, like Borges’ map, the Polaroid can achieve a similar effect of likeness while maintaining its role as a miniature.

I envision my hand scrunched up into a fist, trying to fit through the small portal of a Polaroid, feeling the cold outdoors of the world on the other side, as if the photo was an open window. What would greet me from this realm? Unlike a mirror, all would be as it was, except faded into the colours of memory.

The second thing to consider in relation to Borges’ map is that, unlike those maps of the make-believe empire, we look to Polaroid photos because they are imperfect; their colours are not quite of our reality, their focus is idiosyncratic, their framing forcibly restricted. They do not cover the world with perfect measurements nor give us an exact likeness.

Their ability to insinuate the spatial qualities of a 1:1 map instead comes from perspective and other, ghostly qualities. A Polaroid’s mapping comes from what it ignites in the viewer, becoming a weird fragment of actual, remembered space.

A perfect Polaroid is thankfully impossible, at least on a technical level. The results of those who try to use them as perfectly as possible produce something decidedly odd. Any number of Polaroids appearing on Instagram attest to this absurdity; one which most of the photographers (usually celebrities) lack any awareness of.

The polished Polaroid is a contradiction as it seeks to void what my mind puts back into its expression: the rougher elements of lived experience, imperfection wiped away with the same ease as a photographic filter hiding the shadow of a wrinkle. The more startling photographs draw my gaze with their imperfections as much as overly polished, pristine photos turn it away.

I want to see wrinkles, shadows, horrors and everything else.

These are not simply the imperfections and quirks that Roland Barthes spoke of when he discussed the idea of the punctum; a detail that happened in a photograph’s subject quite by chance. A Polaroid’s punctum, if anything, comes from the subject colliding with its restricted formal qualities, in particular affecting its relationship to space; contained within a bordered context but insinuating something beyond it all the same.

Perfection is death to interesting photography and objects more generally. Borges knew this, hence why such impossibly perfect objects obsessed him. Ironically, the falseness of a Polaroid and its suggestion of a wider space around it is far more effective in bringing us, eventually, back to reality. Treading an imperfect, more human path, it tells of the space inside and outside of the photograph, as well as the space the Polaroid journeyed through after coming into existence.

Let me walk this path, I plead with photographers. Stop cutting the grass, stylising reality out of all meaning.

I want the imperfection of your eyes and your desires.

I want the strange personalities of these analogue machines.

I want your perspective shared with human fallibility.

Do not hide it.

I want you.

On the Road

It would be some years after my initial photographic experiments in Liverpool before I could finally use a proper Polaroid camera. I still remember the day that one eventually came my way. This is because in my mind it was a silver day; shining in my memory because of the place I was in when first looking at the camera.

I had arranged to meet with my friend Ellen that day; an accomplished analogue photographer whose self-developed, hand-coloured photos haunted many a wall in London and still arouse my astonishment whenever I see them.

On a rare occasion when we were both free, we had agreed to meet on the metallic peninsula of Canary Wharf. I had often stared out at its array of monolithic buildings from afar with trepidation, as if it was a landscape akin to Mordor. My visit to see Ellen was actually my first walk around these empty spaces of metal, glass and escalators.

We were meeting because she had brought me a gift. Knowing my love for the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, she had considered it the right time to lend me an old Polaroid camera of hers, one she had used in her days as a fashion photographer.

We sat in the unreal space of Costa Coffee where the attempt to create a sense of the real fell amusingly flat. Ellen put the camera on the cheap wooden table and it sat in even starker contrast to the faux-bistro surroundings. The machine was an alien oblong that folded into itself when not being used. It was an artefact of failed futurism.

The camera was a Polaroid One, a model often advertised as ‘retro’ when sold online, being a popular first camera with Instagram users in particular. However, its retrospective qualities are moot for millennials such as myself, being a camera that is barely older than me.

Its design is rounded like cars from the early 2000s, and it has a handy chord to loop your hand through as a precaution against dropping the thing.

I had bought a box of film for it, already astonished that the rate for taking Polaroids was now roughly £2.50 a photo. It rendered the images doubly precious and requiring consideration; something I was not sure would fit with my own vision of what gave the Polaroids I liked their qualities. The feeling of a photographer snapping away without a care, chancing on the beautiful and eerie, was potentially lost. With each snap, I would not hear the camera’s exciting mechanism growling away but instead the sound of jangling change roughly to the sum of £2.50 falling out of my pocket.

Ellen showed me how to load the camera, opening the film stock which was sealed like perishable food. The mechanism chewed and whirred before spitting out the plastic cover of the stock, designed to protect it from any light exposure. The man on the next table looked at the device with the annoyance more typically reserved for a naughty child so we opted to wander. Even all of these banal things were thrilling to me then, simply due to the exoticness of the camera. I even kept that first plastic cover as a memento.

With the strange looks following us, we walked around the wharf, talking and getting lost while I tried to find things I could use the camera on. All of the buildings reflected each other like a range of cold mirrors and it seemed pointless to photograph them.

First and foremost, I wanted space; in both the context of its subject and in actually travelling with the photo itself, as if the finished Polaroid could be a silent companion taking notes. In other words, taking that first, proper Polaroid required a pilgrimage, at least to my mind, in order to be effective.

Taking a photo of those buildings on Canary Wharf would have been like layering images and ideas pointlessly over each other, the past’s vision of modernity capturing the present’s awful realisation of it. And then I remembered a line of a novel, or at least some its opening gambit which aided my own argument for waiting.

The true light of the high-rise was the metallic flash of the Polaroid camera, that intermittent radiation which recorded a moment of hoped-for violence for some later voyeuristic pleasure.

The quote came from High-Rise (1975), a novel by the British science-fiction writer J.G. Ballard. I then had an idea: my first Polaroid would be a Ballardian pilgrimage, and not simply one in spirit (as Canary Wharf would have undoubtedly sufficed).

I wanted space and journey rather than metallic voyeurism.

I wanted the banality of everyday life rather than vivid commercial depravity.

Like many, I held a deep admiration for Ballard’s writing, his books being an unusual factor in my initial move to London. His novels represent so many different things that interest me that they seem tailor-made for my needs: brutalist architecture, science-fiction, transgressive narratives, detective-pulp styling, forgotten landscapes. Ballard’s work has it all.

The novels I really responded to had been his explicitly London narratives, in particular Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974). In these novels I found a great deal of recognised landscapes, mimicking those I had grown up around (albeit on Merseyside rather than London) and had come to feel affection for. Ballard knew the overlooked edgelands of England more than most writers, and had been one of the few from his period to acknowledge such spaces creatively.

Ballard was a writer with an analogue vision. In fact, I would go further: I see his writing as a kind of Polaroid. His novels have a strict frame through which we observe human subjects evolving under specific conditions, like a clinical social experiment. There is a more specific reason for seeing Ballard’s vision as analogue, however, and it is arguably thanks to the filmmaker Chris Petit as much as Ballard’s work itself.

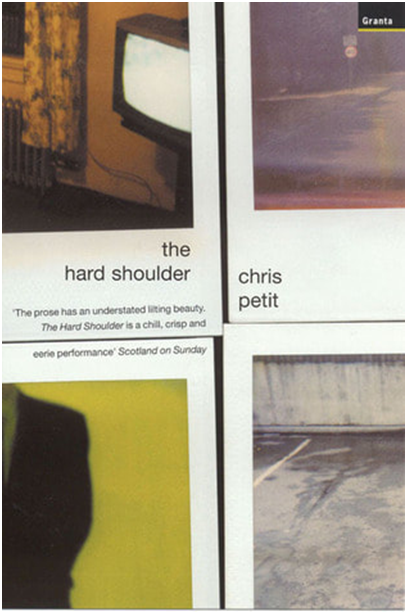

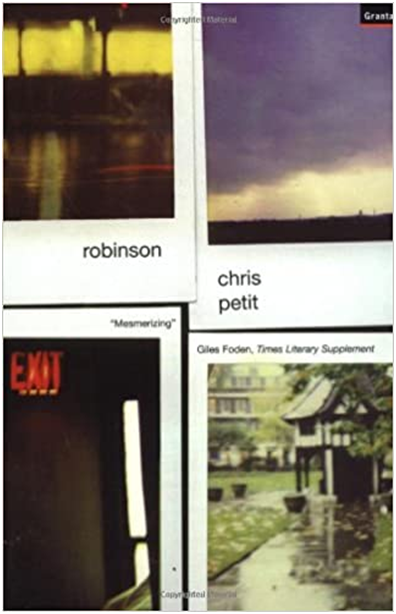

As another Polaroid user, Petit caught Ballard and his world permanently within an analogue frame, marking that typically Ballardian intersection between human lives and everyday technology. Whether adorning the covers of early prints of Petit’s novels Robinson (1993) and The Hard Shoulder (2001), or featuring in any number of his journeying, essayistic films, Polaroids often crop up in his work as well. Both artists embody a Polaroid vision.

In 1990, Petit collaborated with Ballard on a short film for the series Moving Pictures. Throughout the film, many of Ballard’s typical landscapes appear in a series of Polaroid photographs, mostly taken off camera in the film but with the sound of the machine’s mechanism heard several times. Most telling is a segment in the film when Ballard himself is facing the screen, armed with a Polaroid Supercolour 635CL. He clicks the mechanism and then the film cuts.

I often wondered what that Polaroid Ballard took actually looked like, so much so that I actually asked Petit. ‘Ah yes,’ he told me over email, ‘I remember him taking the Polaroid but have no memory of what exactly the subject was. There was a film crew so probably of them, but it seems not to have survived.’ Who knows what journey Ballard’s Polaroid took or where it is now.

Later, Ballard’s vision of the world is illustrated on screen with Polaroids of the landscapes already seen; an airplane in the sky taking off from Heathrow, high-rise blocks similar to Canary Wharf’s towers taunting a dangerously blue sky, and car parks with their bossy language of direction and instruction scrawled upon the tarmac.

Ballard suits a Polaroid camera because its immediacy is violent, and its output is regularly dripping in presence. You can smell the blood and petrol on them. As Petit appropriately suggests of Ballard in his short film, ‘His writing has a quality least associated with our national cinema: vision.’

If we consider the world which Ballard regularly conjured, it is easy to see Polaroids as reliable representatives of them. They gain a similarly grimy presence, recalling stories of under-the-counter pornographers utilising the Polaroid for swift and easy sale of illicit images to the stained raincoat brigade.

Polaroids also conjure Ballard’s world in other ways. The writer’s work was rarely adapted successfully for the big screen. When attempted, such films usually became interesting in just how far removed they were from the writer’s original vision, even when he approved of them; like a control for a failed experiment that no one ever really learns from.

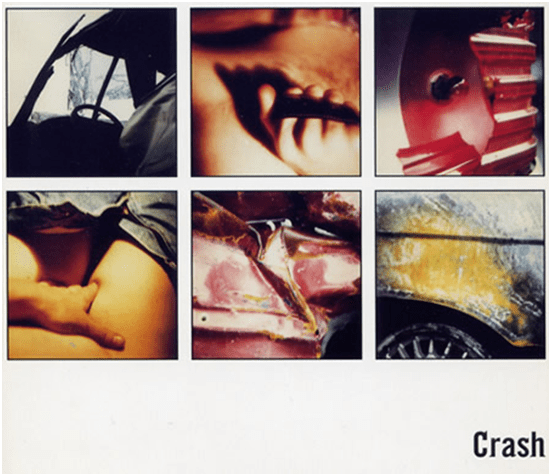

In 1994, David Cronenberg adapted Crash with Ballard’s initial blessing. When I think of Crash, I do not necessarily think of the images from the film itself. Instead, I recall several Polaroids connected to it. I do not see James Spader having sex on the hard shoulder. Instead, I see Vaughan’s Polaroids littering his messy flat.

I see Polaroids of the cast taken behind the scenes.

And I see the cover for the American version of the novel from around the time of the film’s release, designed by Michael Eden Kaye and Melissa Hayden, clearly influenced by Cronenberg’s vision.

To me, all of these images understand Ballard’s world more succinctly than the actual film because they capture space and implied journey with greater ease; no dolly camera or montage necessary. They simply express a dirty voyage into the everyday world and what writhes beneath it.

When the artists of the cover were interviewed about their work for Ballardian, a website dedicated to exploring the writer’s work, they highlighted why the Polaroid is so fitting for expressing the same themes of the writer’s novels. ‘They all represent little blips of the experience,’ Kaye suggested, ‘using the grid speaks a little more to the futuristic quality without being so literal. It was about lots of little ideas making up the whole.’

This is a spatial idea.

They may feel like small blips but, whether looking at one single photo or many, space outside of the image is insinuated. They instantly suggest a world around them, as well as that which has been traversed after their initial photographing. I can envision those journeys easily when gazing at them, whether in terms of the narrative of the work or the reality of their real world production.

With all of this in mind, Ballard seemed a suitable subject for my first proper Polaroid on the camera gifted by Ellen. I had already visited Ballard’s grave in Kensal Green Cemetery soon after moving to London, noticing its strange proximity to that of another writer I admired, Harold Pinter. Perhaps they debate the world and writing after dark.

I had photographed the grave on my lomography box, and had been disappointed by the strange contradictions of the final image. The grain was as soft as the Japanese copy of Ballard’s Super-Cannes (2000) which lay sodden with rainwater next to the grave on that visit. The Polaroid needed a new venture, if only so that a greater space could be mapped.

I decided on another pilgrimage: to Ballard’s infamously suburban house in Shepperton, the unlikely Thames Valley base where his dark vision of post-war Britain first sprouted. I had seen many photos of the writer stood outside this unlikely building, his persona of suburban post-war gentility matching the building more readily than the dark flavour of his work.

The building is now a prized property in the commuter belt and, since my visit, the current owners have gleefully shared their decimation of its beautiful Art Deco design on Instagram; replacing the original surrealist paintings, surviving period features, and reams of books with “His & Hers” mugs, garish double-glazed windows and framed inspirational quotes.

The images I had already seen of the house, on the other hand, had uniquely been taken on analogue formats, so even Ballard’s home seemed built from grainy bricks and imperfect window frames in my mind. It was a place full of contrasts so made for the perfect Polaroid subject.

Armed with my camera, I took the train to Shepperton from a bustling Waterloo and watched the buildings out of the window evolve from endless high-rises into green fields, golf clubs and inviting terraces. Any knowledge of Ballard’s novels renders such a change unnerving rather than comforting; these are the unlikely places of violence in his universe, and my journey was not helped by having taken the writer’s last novel, Kingdom Come (2006), to read on the way. The book’s characters find menace, not in the inner city, but in the outer suburbs of my exact destination. As Ballard himself once suggested, the future is ‘going to be a vast, conforming suburb of the soul.’

Shepperton was the model for this future.

The writer’s house was not far from Shepperton train station, and I noticed a retirement home cheekily named after him at the start of his road. With the town being most famous for its film studios, decades of this association rendered it a quietly unreal place, as if its utterly mundane appearance was hiding something else entirely, rather aptly like a film set.

Ballard’s Art Deco semi-detached was exactly as imagined. Even by the standards of the other prim houses around it, the house was of another time. I snapped my Polaroid and it caught the space; not just the walls of the house but the journey of the day, as if a stopwatch had been started from the point of pressing the camera’s button, endlessly ticking on in my own memory and beyond. I was not sure how long the picture would take to develop and, not wanting to take any chances, I paced the hot, hazy streets waiting for the image to appear.

The Polaroid forced a greater engagement with the space of Ballard’s road simply out of technical necessity. If I had left early and began my walk elsewhere, only to find the Polaroid had come out badly or not at all, then I would have felt the journey to be in some way nullified. I was forced to experience the space on a more detailed level, simply to make sure that I had recorded it properly. Perhaps if the image did come out blank, the space I traversed and the journey undertaken would have still been retained in some way for me in the blackness of the failed Polaroid.

Even a failed Polaroid was there.

Thankfully, my image did not come out blank. As I walked to the end of his street – a road which appropriately ends next to a motorway – I pulled the photo out and saw that it had developed. My damp London bedroom had prematurely aged the stock so already the Polaroid looked like it was from what I perceived to be Ballard’s era. It had that 1970s yellowness now regularly faked with digital filters.

The effectiveness of this aesthetic was confirmed to me some years later when working in the capacity of an advisor on an exhibition of counter-culture material at Somerset House called The Horror Show. In my first meeting with the curators, they used a digital scan of this same Polaroid they had found online in a slide to represent Ballard’s eerie 1970s spaces, totally unaware when showing me the slideshow that it was my photograph, and that it was taken during the previous summer rather than several decades ago as they had believed.

In fact, the level of deception was so strong that they believed the photograph to have been taken by Ballard himself, something I was quietly rather proud of. Only I, with my muddled array of admirations, could take pride in having a photograph of mine pass for being taken by a great writer rather than a great photographer.

The photo conveys condensed space, rather like those images ever popular online of every frame from a film layered into one single image. A Polaroid is rather like this on a personal level; and more aesthetically interesting as the rest of the film’s frames, the frames of your life, are contained within you, memorialised. I can see the sweltering pavements from that day in the photo, buckling and crumbling under the excessive amount of cars, the pub that sat cosily between the houses and, generally, the whole journey undertaken to see Ballard’s house.

Even if unaware of the minutia of my day and its journey, some space or distance should be perceivable in the photo.

Because the Polaroid exists there and then, it travels in a way that imbues the object with other qualities outside of visual recreation. Undoubtedly its subject will affect interpretation like any other photo, but the Polaroid’s existence alone speaks of some insinuated journey, no matter how short. The photographer must have travelled from somewhere, and the finished photo must have gone with them.

Ballard understood the Polaroid, and saw fit to put the object in his novels, alongside the other technological developments that came to define his era of writing. The Polaroid camera feels just as apt for stories like High-Rise or Crash as blocks of flats, a motorway or daytime television. Perhaps this is why the images produced by a Polaroid camera have a certain edge to them; their aesthetic does everything in its power to convey ordinariness, suburban ordinariness even, to the point where Polaroids seem to say ‘Please ignore.’

It is a suspicious object, more likely to be stopped and questioned due to its own attempts at avoidance. They are the missing witness to the moments they convey, the purloined letter hiding in plain sight framed on the wall. In being so utterly ordinary, they become endlessly interesting. And in capturing the spaces they journey through, they, too, become something as fantastical as imagination itself.

This is terrific, Adam. I love the Polaroid of Ballard’s house with its ghostly glistening tracks left from the camera’s rollers.

Thank you Terry!