‘We were here, too, once and please take care of us for a while.’

‘With digital technology,’ wrote memoirist Annie Ernaux, ‘we drained reality dry.’

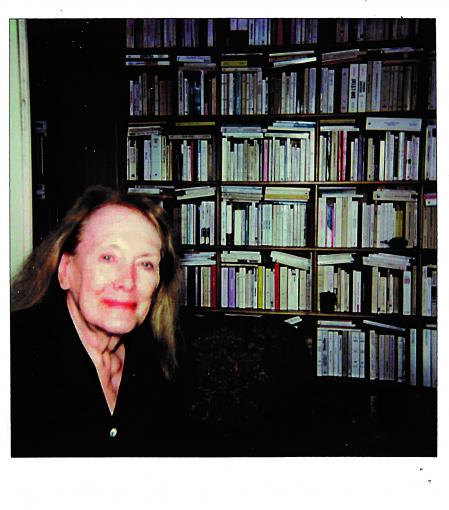

As digital creatures, we carry out an endless taxidermy upon our experiences in the ever frenzied pursuit of content. Ernaux’s poignant criticism echoes Susan Sontag’s earlier weariness at what cameras had done to our ability to simply live, and also reflects the constant deluge of digital images this side of the millennium, multiplied tenfold by social media and online culture. It, therefore, feels appropriate that Ernaux released some blurry Polaroids of herself after she received the Nobel Prize in 2022, a prize given to her for, among other things, ‘estrangements and collective restraints of memory.’

Today we carry vast archives of our passing experiences in our phones, no longer simply communication devices but cameras, portals to our second lives online and everything else in between.

Digital life is not merely accelerated by technology, but by instant access to that technology: the handheld revolution. We accept, through capitulation to this revolution, that our lives are firmly in the past tense, every moment no longer primarily experienced but distanced and mined for potential sharing. Our very actions have become preordained by their eventual future retelling. We are increasingly prisoners of a dead future.

Digital photography shares some aspects of the instantaneity of Polaroid photography but neither its mysteriousness nor it strangeness. The past tense is openly celebrated every second in the digital realm, seen as the natural state of all our lives. The Polaroid on some level shares in this, but has the ability to age and to gain new meanings along the way to balance things out.

Being both a millennial – a generation that has never really known anything different to the ephemeral digital world of today – and someone who prefers the finitude and limitations of analogue technology, my mind is constantly engaged in a tug-of-war between a natural leaning towards digital immediacy and a growing love for analogue artefacts.

Analogue is more human in its imperfection. The Polaroid is the epitome of unique mistakes. The focus is soft, fixed and easy to blur, the light is sometimes harsh, unforgiving and brutal, and the framing is stubborn and difficult to manoeuvre. Even its potential digital scanning is tricky and awkward to position.

It is as imperfect as we are.

Digitalism attempts to reverse all of this, ingraining ease and likenesses into all our expressions, from subject to aesthetic. Analogue media positively revels in difference, especially in its fetish existence within our current age of nostalgia and mourning for a more tactile sense of living. Even its mistakes and distortions are interesting today, to the point where great efforts are made to recreate them.

Digital filters mimicking analogue grain are the pre-ripped jeans of photography.

A Polaroid’s domesticity renders its subjects different to our own modern fascination with the everyday. Whereas life can be edited to a greater degree than ever before in our own curated projection of what we are doing, the same interest in the everyday I have found in old Polaroid photos is something else entirely. It is curious rather than performed, eerie rather than banal, alive rather than undead.

A viral photo of a cat, turned into a meme and seen on a screen millions of times, still lacks the presence of my found Polaroid of the kitten investigating the television. The Polaroid was there in that moment. The meme of a cat seen on a screen never existed at all, except as a real cat and later as pure information.

When considering why, even with its similar immediacy, digital photography ultimately fails to achieve the haunted presence of a Polaroid photo, I find myself returning to a quote from the writer W.G. Sebald.

Known for littering his novels with a range of images, including found photographs, Sebald’s ideas are naturally prescient. In an old interview he gave for television, he was quizzed about photographs, why he used them in his novels and what it was about them that interested him. His answer was succinct and important:

The photograph is meant to get lost somewhere in a box in an attic. It is a nomadic thing that has a small chance only to survive. And I think we all know that feeling when we come across, accidentally, a photographic document being of one of our lost relatives, being of a totally unknown person and we get this sense of appeal… All of a sudden they come stepping back over the threshold saying “We were here, too, once and please take care of us for a while.”

He is discussing the power of a physical photograph’s incalculable destinations, with the living subjects themselves calling back through time like phantoms.

The photograph is a nomadic thing. It wanders in and out of our lives with such startling ease that it is surprising to find any surviving at all. Sebald dramatises the human subjects of a photo as if they themselves are reaching out from within their sepia past towards us, asking to be remembered.

Sebald’s idea epitomises the feeling of company I have felt, the same haunting that washes over me, whenever finding the discarded Polaroids of strangers; washed up on the shoreline of my life like intriguing messages in a bottle. He even suggests wandering to be photography’s paradigm. Their point is to be lost and then found.

What happens to photography when becoming an object is no longer its primary destination? For me, this is what negates interest in digital photography’s immediacy: it never has anywhere to go in the real world before entering its afterlife (where its subject drives any interest in it).

The destination of a digital photograph is absent. It has no specific physical conclusion. Digital photographs are born into their own afterlife because, for the majority of the time, they only exist as echoes. If analogue photos enter a ghostly life once developed, used in all sorts of other media, even digitally, there is still at least the original print or perhaps the negative left behind.

When we first see a digital photo, it is usually on the screen of the camera that has taken it, whether a regular digital camera, a tablet or a phone. In the context of photography since its inception, digital photography has no primary destination as it rarely exists in the real world as a photographic object. It merely stays on the screen.

It can adorn the covers of magazines, album covers, film posters or whatever else in just the same way as analogue photos, but the photographs that are used for those things have never required existence in the physical world. It is data, matched from the rays of light reflected off a mirror and stored on a small SD card, hard-drive or Cloud. If it was lost like some of Sebald’s photographs, it would mean certain oblivion, a digital spirit exorcised. It can forget the possibility of an Orpheus-like journey back to us in years to come.

There is no return from the other side for digital photos. They are still-born.

Thinking back, I recall digital images being my first experience of photographic immediacy. Looking at the screen on my father’s first digital camera in the early 2000s was a strange experience, partly because it was exciting, partly because it was disappointing. He eventually printed off a variety of photos once uploaded to a computer in order to make up for this disappointment. They still ultimately lacked something.

Even if printed in the same size and format as an analogue photo, a digital photo is still missing any real solid source to draw back to, no corpse for the ghost to look upon mournfully in reflection of the life long since passed. Digital photos have never really been except at most as a blip of a vast carbon footprint caused by its storage on some anonymous mass cache system or personal equivalent. It exists solely in photographic purgatory.

Photographic discussion is ironically so often driven, not by the reality of the photo being an object (at least before the millennium), but by its subject; rather like focussing on the narrative of a film rather than the mise-en-scène used to tell it. This assumption arguably fed into the acceptability of digital photography. Photography today really means any form of information transmitted through some fixed visual rendering.

Images over objects.

Holding a Polaroid makes me feel briefly alive again in a world increasingly devoid of touch, and makes the subject it contains feel lived, building a stronger continuity between their then and my now.

We are a world increasingly reduced to a depressive catatonia through images and digital gluttony. The algorithmic force exerted upon digital photography removes any last essence of potential presence, no matter what other qualities such photography provides (of which, in spite of these criticisms, I find many when taken back to simply considering them through their subjects).

Teju Cole’s discussion of digital photography in the social media age possesses the most appropriate bite in this regard. ‘Behind this dispiriting stream of empty images’, he writes, ‘is what the Russians call poshlot: fake emotion, unearned nostalgia.’ With no defined destination, digital photography is susceptible to poshlot, craving it even, as photographs cry out for meaning and existence.

I imagine a psychic medium on a low-brow television programme communicating with these dead photos, their spirits asking for help to cross to the other side, away from the purgatory of hard-drives and Clouds. But their wish is never granted.

They remain absent, locked in silence.

Presence

With the destination of a Polaroid allowing for more experiences and events to befall it, it gains something from taking the short cut to existence: presence. This book is about the haunting effects of this, but what then is the presence of a Polaroid?

I believe presence is the charge of being in the moment, existing as close to it as is possible, something that provides Polaroids with an unusual sense of perpetual living.

Space and time appear augmented by the Polaroid in ways that other forms occult and mask. It drinks in memory and death like a thirsty wanderer in the desert. It threatens to release its older moment into the now, simply through a possible break in its frame. This potency and proximity to real life allows the Polaroid to retain something of the moment it memorialises.

Such power has been discussed in general since people first began to think about photography. Walter Benjamin called it an aura but, while this is a potent idea, there is something that does not quite fit when applied to a Polaroid. Benjamin describes aura as a ‘gossamer fabric woven of space and time: a unique manifestation of a remoteness, however close at hand.’ It is a poetic description, and vague enough to seem applicable, but not quite fitting the Polaroid. They are far from remote.

In this most mechanical and commercial of forms, I experience a certain aura. I call it presence due to its proximity to what charges all artwork to some degree: lived moments, and how Polaroids seem to carry these ghosts within. Something is there.

Aura is even more fascinating as an idea considering that Susan Sontag described Benjamin’s very idea as ‘presence’. ‘Another criterion which they can share is the quality of presence,’ she argued. This was not an idea applied to Polaroid photography, however.

To bring us back to the everyday, a television programme accidently highlights for me the overwhelming immediacy of the Polaroid, even if failing to express the deeper possibilities of presence. Ideas do crop up in the most surprising of places.

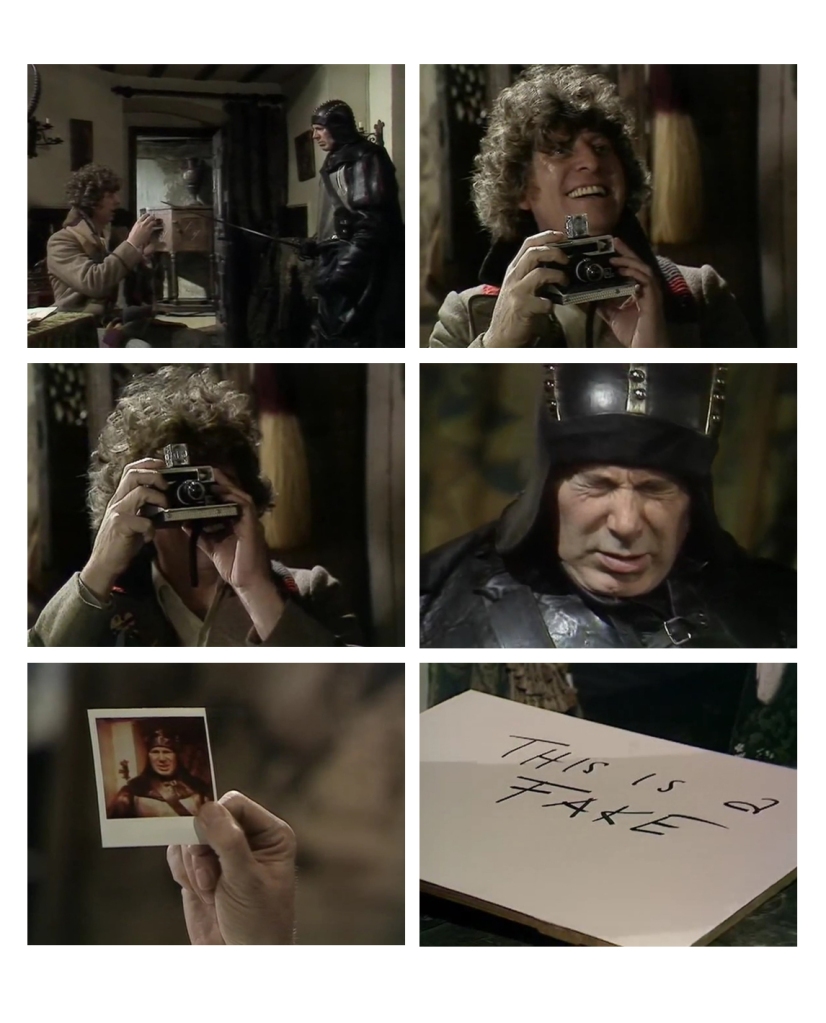

In 1979, the author of the celebrated The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy novels, Douglas Adams, was script editor on the BBC science-fiction series Doctor Who. Writing under a pseudonym with fellow writer David Fisher due to rules against script-editors penning their own scripts, Adams co-wrote one of the wittiest and most celebrated of stories City of Death.

Set in modern-day Paris, though travelling variously through time and space, the story revolves around an alien pushing forward human civilization and technology in order to build a time-travel device to go back and stop himself from destroying his own race. The modern day iteration of the alien covers the extravagant cost of his time-travel experiments by selling artefacts and works of art, enabled by his being fragmented throughout history. The objects central to the story are several copies of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, all of which are mysteriously and impossibly genuine.

One scene late in the story features a Polaroid camera, and it may have been my first instance of seeing one used. The Doctor (all scarf and Tom Baker curls) travels back to Renaissance Italy in order to discover just how the alien has managed to get Leonardo to rustle up several copies of his most famous painting. He is captured by another fragment of the alien working for The Borgias and is under guard awaiting torture by thumbscrew.

His method to escape, which admittedly fails, is to take a Polaroid of the guard. The Doctor whips out the camera, snaps the Polaroid and gives it to him. The guard is so taken aback by his own image that the distraction is enough for The Doctor to thump him unconscious, giving him enough time to write ‘This is a fake’ in felt-tip on the canvases that da Vinci will use for his other Mona Lisa paintings. The irony is that the one Mona Lisa to survive the later destruction of the alien’s Parisian mansion (and be subsequently returned to The Louvre) is one that has The Doctor’s inscription underneath the paintwork. Does it matter though if the image is real and Leonardo painted it?

The Polaroid in any realm, real or fictional, is a witness in the most genuine sense; and that sensation can be unnerving (even if more familiar with the possibilities of photography than a Renaissance Italian guard). The present ages as we look at a Polaroid. It is strange evidence of the world around us and our place within it.

No wonder the guard was so shocked by his image.

Instant Memories

Polaroids furnish us with what Geoff Dyer calls ‘instant memories’. ‘The present was turning to the past before his eyes’, he wrote of Walker Evans’ later Polaroid photography, ‘everything he saw was like a memory of itself.’ It is presence that creates instant memories, even when we are not as skilled as someone like Evans.

If photography generally offers instant romanticism of the present, then Polaroids do this quicker than any other form. I can take a photograph of a grave and the subject will still be distractingly romanticised, even if its subject is connected with death and loss.

Over the years, I have developed a habit of photographing graves. They ironically offer endless possibilities. I thought it appropriate, having earlier mentioned the writer W.G. Sebald, to conclude with a Polaroid of his own memorial, making an equally wandering object to be lost and found in some distant future. The Polaroid I took of that visit still carries the presence of that day.

Sebald, or “Max” to his friends, was born in Bavaria in 1944. In the mid 1960s, after studying in Germany and Switzerland, he travelled to England where he taught at the University of Manchester. He soon settled in Norfolk, working his way up the academic ladder at the University of East Anglia. Though publishing late in life, Sebald’s writing career took off quickly. His novels The Emigrants and The Rings of Saturn, translated into English in 1996 and 1998 respectively, secured him an astonishingly rapid literary success. Such a rise in the literary pantheon was unparalleled, so his unexpected death in December 2001 cut short a career that clearly still had much more to give.

With his novels explicitly connected to a sense of place and photography, I had already visited and photographed a number of Sebald-related sites. From the East Anglian locations walked in The Rings of Saturn to the East London haunts in his final novel Austerlitz, I had spent a great deal of time walking after Sebald, chiefly out of curiosity. There is little doubt that, with his mode of writing being fictional, following in the footsteps of his narrators is a pastime that generally reveals discrepancies rather than synchronicities between novels and places, illusions heightened further by the photographs he himself took.

Of all of the places seemingly marked by the writer, the one I had avoided up to then was his grave. There could be no misreading of this place, no characterisation or editing on the writer’s part. It was a depressingly early full stop to what should have been a much longer series of sentences. But, having searched for so many Sebaldian places, it felt the right place to end what had been almost a decade of obsession.

Sebald is buried in the Norfolk churchyard of St. Andrew’s in Framingham Earl, not far from where he lived in Poringland. The church is a typically East Anglian building, bustling with antiquity and wildlife in equal measure, and possessing a beautiful Norman round tower which must have loomed out across the fields as a beacon several hundred years ago.

The day of the visit was tarmac-warm and blindingly sunny. My birdwatcher father, who was with me for a weekend break, was keen to travel further north from where we were staying in Suffolk in search of a lost great grey shrike, blown haphazardly onto the Norfolk coastline. Before heading in search of the confused bird, he kindly drove me to Framingham Earl to see the grave.

I walked around the churchyard, my father accompanying me while looking at the butterflies, and Sebald’s grave quickly came into sight. Made of a jet-black stone, it stood out among its lichen-covered neighbours, and was littered with mementos; from a vase of flowers to a variety of pebbles carefully placed along the grave’s head. Blue damselflies seemed unusually drawn to the spot. The insects are fond of his grave.

I was armed with my more typical Polaroid camera then, and snapped two images, letting them develop between the pages of a Raymond Chandler thriller. If unfortunate enough to lose both of the photos, perhaps they could one day end up used in a novel like Sebald’s. I, too, was here once.

As the Polaroid developed between the pages of Philip Marlowe’s Los Angles exploits, it seemed the right time to stop following Sebald. Yet, in hindsight, it also felt as if all of that trip was mapped by those two images.

The photo sketched an emotional cartography of my own memory, the spaces traversed that day, even the thoughts I had then regarding death and the ability to live on through work. In hindsight, it feels like a journal entry that only I can fully read, such is the detail of the world that the Polaroid conjures each time I hold it.

Presence caught within a Polaroid does more than iron out the creases of our lived situation. It also does more than provide some nostalgic comfort for the coming future when we will cherish things which furnish us with evidence of what we all ultimately lose. It can question our perception of the world around us, our sense of self within the past, and foreshadow the eventual disappearance of us all.

In other words, presence gives Polaroid photography a unique perspective on space, time and death. They are rare witnesses to human experience: gone but, like ghosts, refusing to be forgotten.

2 thoughts on “Presence, or Polaroid Ghosts (Part 3)”