By the time I was growing up in the 1990s, the previous decades of the Post-War years had been heavily codified. The 1950s were very much the 1950s; the 1970s were very much the 1970s, and even the 1980s – the decade I was born in the last year of – were very much the 1980s. The BBC in particular milked this realisation for all it was worth with an endless slew of “I Heart the 1970s” and “Sounds of the…” style programmes, constant re-runs of classic shows and nostalgia tinged compilations like Top of the Pops 2.

The shared collective cultural experiences of those times, of whose keynotes usually make up a very generic vision of each period, is often the first step in experiencing previous eras when growing up. Their music, clothes, films and television all feed into it, and enjoyably so, even if overly simple as a way of understanding each era (I often think the first half of any given decade has more in common with the previous decade’s latter half than its own). So, when thinking about my own first experience of the 1960s as a cultural moment, even more specifically a British cultural moment, something odder happened; namely that half way into the Sixties (and really into the early half of the 1970s), more than any other period, a kaleidoscope of eras was evoked, from Georgian Regency to Victorian fairytale. The decade is most haunted by a colourful, handpicked enjoyment of much earlier British culture.

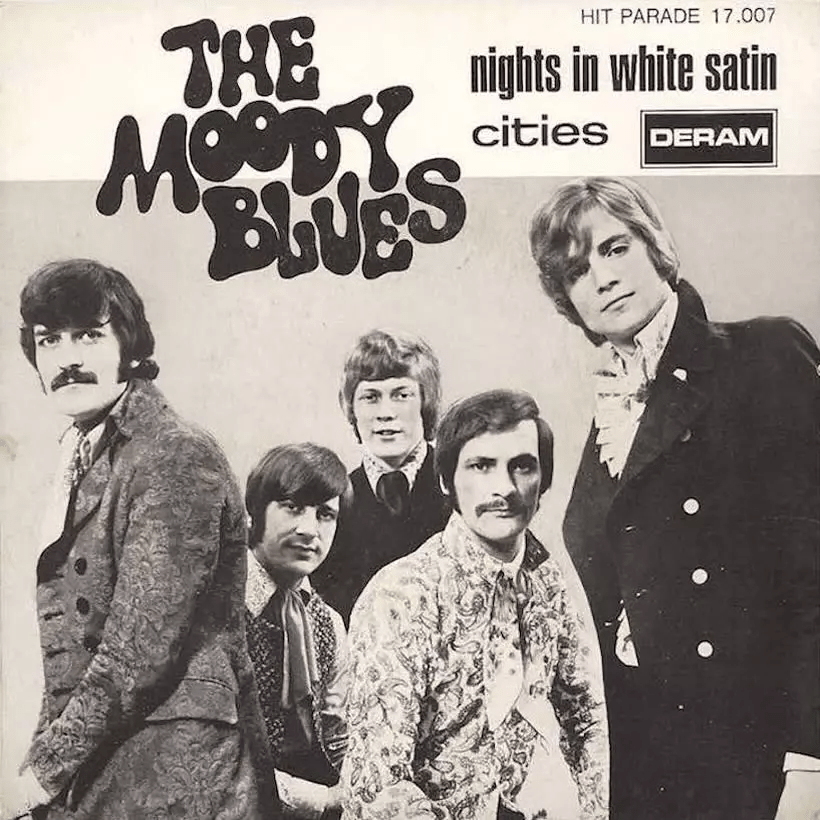

In spite of encountering a huge amount of Sixties culture virtually from birth (being from Merseyside, this is unsurprising), the first instance where my childhood mind actively recognised something as being from the decade also recognised it as being in touch with a kind of abstract past. Though the decade is itself split into different, smaller moments, its interest in the past bubbled away. My instance of first recognising the Sixties was, of all things, in a specially recorded video of Nights in White Satin by The Moody Blues. I’ve never been totally sure about the origins of this video but it seems like one of the high-end jobs that Top of the Pops would occasionally commission; shot on good quality 16mm and likely not enough reel to make something too extravagant, hence the repetition of shots. In that strange little courtyard, the Sixties were made manifest, or at least a certain iteration of the era.

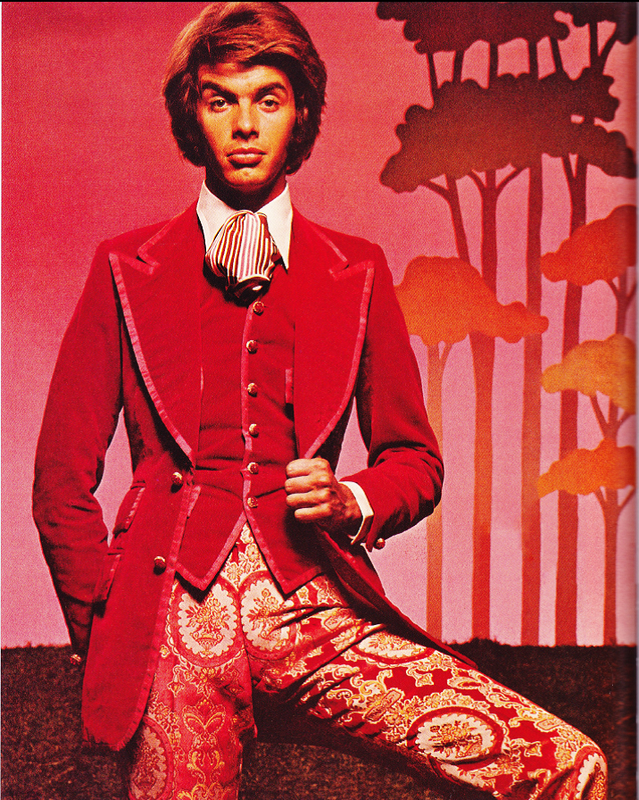

In the video, the band simply mimes along to the song. But it’s the styling that really stuck with me. All four members are dressed in the height of Regency Mod glamour. This is well past the earlier Peacock Revolution in which vast arrays of colour, patterns, frills and generally older forms of fashion had been adopted by a growing array of hip and happening young things, especially men for whom tradition and rigour had been pretty much a given until then. Justin Hayward is especially Beau Brummell-esque with his attire, while flute player Ray Thomas looks like he’s auditioning early for the role of Jon Pertwee’s Third Doctor; all frilly cuffs and a jacket straight out of Regency pomp.

More than the fashion, other aspects of the video hinted at the Sixties as a period interested in older eras. The building they’re stood in front of is notably old – almost like the building from a whimsical fairytale – while the director of the segment pays almost obsessive attention to the ornate metalwork of a nearby gate and the way its design seems to blend quite naturally in with the neighbouring leaves and foliage. All very Art Nouveau. Yet also very swinging.

Recognising this strain of cultural interest has provided a real pleasure of late; understanding that the middle of the Sixties in particular (post-kitchen-sink, pre-68 madness in particular) was a haven for artists and the general public to indulge their interests in the previous 250 years or so of lavish, foppish culture. The greater the excess, whimsy and absurdity, the greater the aplomb with which it was embraced. This, perhaps, is the key to understanding some of the culture about to be discussed; culture which opened very specific windows onto the past and created a kind of idiosyncratic foppery clearly expressing something tangible to Sixties British culture as well. The past had of purchase for Sixties Britain.

The Colourful Past

The smorgasbord of the counter-culture’s past is enjoyably apparent in its television. It’s certainly present in a variety of ways in the stranger end of pop and rock (as we’ll come back to later) but television is the most interesting for me. The first example that comes to mind is the whimsical oddity of Jonathan Miller’s Alice in Wonderland (1966). A BBC play of startling visuals and originality, the adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s story is ripe for cherry-picking the past. Miller’s adaptation is filled with the kind of nursery rhyme surrealism that took a hold of the decade as it morphed from hip and happening beatnik roll-necks to psychedelic colour explosions. Peter Cook’s casting as the Mad Hatter epitomises the kind of cultural moment here; the kind later exemplified by Syd Barrett.

There’s something of a stylish overlap between Miller’s film and the video for The Moody Blues. Both evoke that Victorian country mansion fantasy; this aspect is the most specific taken from the nineteenth century by the swinging Elizabethan. In fact, Carroll is a good model for what I’m talking about, too. Few would suggest that he represents any particular strain of his period beyond its very upper echelons. Reams of Dickens attest to the fantasy-world of Carroll and the harsher realities of the era. But it’s tellingly what artists of the Sixties were drawn to. Perhaps it’s the madcap nature of it, the total divorce from any kitchen-sink reality that chimes so well with them, as well as a total disregard for anything truly serious. It’s a kind of Victorian drop-out culture for the upper class. All of the culture referenced here seems to be the most off-kilter of its period, yet also revels in the frivolous.

Whimsy is, in itself a constant in this strange timelessness. Think of Oliver Postgate and his 1974 series Bagpuss. I’m cheating a little here as it was a show made during the following decade, though I think I’m justified in how much Postgate seems, like Syd Barrett, to never really leave the previous decade’s bohemian nursery behind. Tellingly, Pogle’s Wood (1965) also somewhat fits the bill if needing an actual example, and even The Clangers (1969) possesses a kind of Victorian child’s amusement, like a finger puppet theatre put on by children for parents.

Anyway, back to Emily and her saggy cloth cat. Emily’s shop is one of the ultimate expressions of this relationship to the past. Emily feels equally a Victorian child and a counter-culture Sixties child just like Alice; a lighter cousin, too, of those found in The Innocents (1961) or Village of the Damned (1960). The children of the latter, in spite of being in the modern day and alien, most resemble the stiff, out-of-time absurdity of Victoriana as well. Even the sense of the bric-a-brac shop for Emily to show lost things and find them a home feels distinctly of both periods. Her very name evokes a previous epoch and its quaint, fairies at the bottom of the garden atmosphere. There’s a reason why the name works for the child in the lyrics of Pink Floyd’s See Emily Play.

Not every aspect of this strange expression was so whimsical nor naively childish. The adventures of Sherlock Holmes found swinging purchase in the colourful Peter Cushing adaptations of 1968, while Douglas Wilmer (the most underrated of Holmes) is arguably the closest to a swinging Sherlock in the 1964-65 series. At times, his dandyish rendition feels as though he could step right out of the series and directly onto Carnaby Street or the King’s Road. His attire, his eccentric manner, his approach to the problems as a game; all expressions of the past being a fun and vivacious realm.

Period dramas of all kinds were far from stuffy or regimented either. The crimes solved by Sergeant Cork (1963-66), the weird encounters of Mystery and Imagination (1966-70), the endless slew of more energetic Dickens and Brontë adaptations; all seemed to see the past with just that bit more colour, more energy, more life.

Perhaps the greatest exponent of what I’m getting at is work by maverick director Ken Russell. For Russell, the past was anything but grey; as wild and swinging as his first full decade of creative filmmaking at the BBC. This manifested in various ways. His stylish dramatisations of the life of Isadora Duncan (Isadora, 1966) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Dante’s Inferno, 1967), seem to be firm arguments in the director’s mind that the past was just as free and loose as the (supposedly newly free) present.

When Russell moved on from mere biopics to actual period adaptations, this became even more obvious. His adaptation of Women in Love (1969) is arguably the strongest example, before the strangeness of the decade’s obsession tipped all of these ideals sideways. Putting aside the latent eroticism on display, the real evidence of the kaleidoscopic past comes from the film’s opening segment when Gudrun (Glenda Jackson) and Ursula (Jennie Linden) are walking through their mining town to a wedding. The town is industrial and bleak, almost a perfect rendition of the earlier penchant for cobbly social realism. But the characters? They stick out a mile in their surreal, colourful attire, and they know it. Their clothes draw scorn from several women, but it’s really an expression of Russell and his period rather than uniquely D.H. Lawrence’s. It encapsulates perfectly the decade’s increasingly swinging view of the past. But things were about to turn even stranger.

The Past Returning

There’s a moment towards the end of Magical Mystery Tour by The Beatles (the song, not the film or album) that has always struck me. After a confident, colourful few minutes of hypnotic, surreal pop, a haunting but short piano line comes in. The piano has some reverb applied so it already feels like it’s beaming in from some echoing past; but even with this, it feels out of time. I used to feel that you could walk through this piano motif and into the Sixties. Now, I feel that listeners then likely felt something akin to walking into this abstract past of Regency dandyism and whimsical Victoriana combined.

The connection between the abstract epoch past and the decade gradually became more literal in culture as time went on. The Beatles were only one of the exponents of this distinctly British connection, often acknowledging an older English culture in a variety of arrays. Think of their styling post-Revolver, their instrumentation that seemed a half-step in Victorian music rooms, musical halls and northern town brass band variety culture (Fixing a Hole, Penny Lane, Strawberry Fields Forever etc.), or even Peter Blake’s Sgt. Pepper cover which pretty much threw everything but the kitchen-sink of the past into the world-building of the band.

The Beatles had nothing on The Kinks in this regard; a band steeped in a kind of abstract nostalgia for some amalgamated past. The village green they were so keen on preserving was arguably one of the mind than an actual Thomas Hardy/Anthony Trollope-esque village green. But the ideals manifest in a huge variety of ways in their work. Consider the typography of the later album covers, a kind of cross between advertising for a steam-engine country fair and East End Victorian music hall act. Or the increasingly old world instrumentation of their music in songs such as Two Sisters and Village Green. Even Ray Davies’ lyrics are open about a harking back:

You keep all your smart modern writers

Give me William Shakespeare

You keep all your smart modern painters

I’ll take Rembrandt, Titian, Da Vinci and Gainsborough – 20th Century Man, 1971

Or:

Like the last of the good ol’ choo-choo trains

Huff and puff ’till I blow this world away

And I’m gonna keep on rollin’ till my dying day

I’m the last of the good old fashioned steam-powered trains – Last of the Steam-Powered Trains, 1968

Ray Davies is arguably the most overt musical addict of the abstract past, such is his dissatisfaction with the present. Yet they were simply reflecting a cultural moment that found purchase in a variety of other expressions beyond their own cultural turn. The aforementioned Russell is a great example of how this connection can work in a very literal way.

Russell went beyond making period dramas colourful and bohemian. In The Debussy Film (1965) made for the BBC’s Monitor slot, he literally brings two worlds together; the fin-de-siècle France of Claude Debussy (all affairs, parties and radical creativity) and the kind hip culture of the Sixties with its wild parties and The Party’s Over eccentricity (Russell cast beatnik for hire Oliver Reed after his similarly horny, hip role in Michael Winner’s 1964 film The System, again telling). Russell could have treated his subject in the same fashion as the many others whose lives he and Melvyn Bragg dramatised, but something clicked with making a more metaphysical film. In a similar fashion to Harold Pinter’s eventual rendering of John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman for Karel Reisz, Russell sees the era and life of Debussy as having some connection to the tastes, trends and behaviours of his time. In order to express this, he makes a film about making a film about Debussy to excuse this temporal back-and-forth. Unlike in his other films, he earnestly links the eras together rather than merely applying current trends to a past period.

Other culture took this to even greater literal heights. Patrick Troughton’s era of Doctor Who is full of superb examples. In the final story of his first season, The Evil of the Daleks (1967), swinging sixties London is eventually connected to a Victorian manor house invaded by Daleks. There are a number of aspects to discuss with this, though the story is sadly missing from the archives bar the second episode and the audio. The first is that Dudley Simpson’s score has a similarly Magical Mystery Tour piano; slightly out of tune, reverbed, old world. This musical form becomes a kind of motif in the era more generally for its rendition of the past (like Death of a Clown by The Kinks). The other aspect to mention is the antiques shop in the episode. A whole separate article (coming later) could be devoted to the era’s wonderful and entertaining relationship with antiques shops; forever realms of strangeness, camp crime and even horror. Here, a Victorian out of time is transporting items from his own era to sell for huge sums of money. However, it’s simply a ruse to trap the Doctor (Troughton) and Jamie (Frazer Hines) so they can be kidnapped and taken back to the Victorian era for the Daleks’ evil purposes.

In a wonderful moment of realisation, the Doctor points something out to Jamie about the shop. Here’s the script exchange:

JAMIE: Hey, Doctor, you know you told me outside it said Genuine Victorian Antiques? Well, all the stuff in here’s brand new.

DOCTOR: Hmm, you’ve noticed that.

JAMIE: Of course I did. The man’s a rogue.

DOCTOR: Yes, so it seems. Except…

JAMIE: Except what?

DOCTOR: Except that all these things are not reproductions. They’re all genuine.

JAMIE: Now, that’s ridiculous.

DOCTOR: Here, look at this. To one deed box, four guineas. This is a bill from William Dearing and Son, 1866.

JAMIE: Then it’s a forgery.

DOCTOR: Yes. If you were going to make a forgery, wouldn’t you try to dirty it up a bit? Yellow the edges, crinkle it up? This is brand new.

The characters essentially touch upon what I’m trying to get at here, albeit the character who’s importing the antiques through time (father of the soon-to-be-companion Victoria played by Deborah Watling, appropriately Victorian as it happens) has more pressing matters driving him to make the connection between eras. These items don’t need dirtying up to pass for the real deal as they fit perfectly well into 1960s Britain in this period anyway. They don’t need a patina applied because the ideals of the past are already reasserted throughout the era’s culture. It simply doesn’t matter.

Other Troughton stories come to mind as well, though none so overtly. There’s the creepy Victorian nursery imagery of The Mind Robber (1968) with its toy soldiers (though perhaps the William Hartnell story The Celestial Toymaker (1966) could also count in this regard); there’s Dudley Simpson’s strangely music hall honky tonk piano score in The Seeds of Death (1969); and there’s the character of Isobel (Sally Faulkner) in The Invasion (1968) showing off her old gramophone player and its Teddy Bear’s Picnic record to Zoe (Wendy Padbury).

While many similar series brought the same ideals of abstract pasts into Sixties culture, the dashing old civil servant-isms of John Steed (Patrick Macnee) in The Avengers (1961-69) and the Edwardian Boating nightmare chic of Number 6 (Patrick McGoohan) in The Prisoner (1967-68), one final series is worth discussing: “Adam Adamant Lives!” (1966-67). The series, starring Gerald Harper as the title character, was made initially as a response to the success of the aforementioned Avengers, especially when that series moved from more nuts and bolts espionage to the surreal, fun kitsch of the Steed and Peel years. However, rather than harking back to the ambiguous past through style alone as Brian Clements’ series did, Donald Cotton and Richard Harris’ show brought the past back literally.

Adamant is a swashbuckling Victorian hero, transported forward to, as his sidekick Georgina (Julia Harmer) informs him early on, the “Swinging city”. Though he finds the morality of the place somewhat off kilter to his gentlemanly world of late Victorian London, it seems that he generally does fit in. In spite of not changing his outfit of nineteenth-century dinner-party attire, he doesn’t seem to attract much attention among a London teeming with Regency Mod and Peacock fops. Several promo photos show the character with the trademark sixties mini (he manages to live atop of a brutalist car park), while even general photos of the period show Harper in real life donning a kind of (beautiful) costumish attire for being out and about in the city. Even the programme’s logo has an essence of the past and present’s collusion (similar to The Kinks’ various typographies and stylings); both era’s seem about stylish adventure and attention-grabby dandyism.

While many examples could be used to further extend the point (especially in music which has a seemingly endless avenue of potential, from obscure acid folk albums to Cream’s old cockney sing-a-longs ending Disraeli Gears), there’s enough here to show the point: the 1960s looked to the most eccentric, dandyish aspects of the past, and brought them forward with little anachronistic friction, and certainly without the cloying, clever-clever emptiness of later Post-Modernism. The past for the Sixties was a realm of careless frivolity, and, for a time, it was refreshing in its emphasis on the trivial and diverting rather than so-called urgent and necessary. It’s something that quickly evolved, changed and gradually disappeared as the counter-culture influence of the following decade died a death and it turned to more manic political posturing. But, for a time, the culture held sway and the past with all of its vibrancy and colour, really was the mode of the day.

Have to post a very quick comment here – this is just wonderful. It’s just one of those moments where you think ‘someone gets it’ and all the more heartening given I was the target child audience at the first broadcast of Bagpuss, already absorbing all the rest of this ‘culture’ that seeped deep into my consciousness leaving me with what, and I think it was Douglas Coupland that said something like this, an ache of nostalgia for a time I never knew – and yet you’ve come to all this growing up in the 90s. Heartening because it’s there to be found for anyone, forever: the something rich and strange from these few years in the 60s and early 70s. (Even though in my own blog I deny it’s anything to do with nostalgia, it’s a type of imagination.) So many threads and thoughts buzzing from this post I’ll have to blog again. But thank you. A brilliant post, once again expressed so beautifully without any sense of ownership or lecturing that so often taints attempts to put this kind of thing into words.

All got me thinking again of Michael Bracewell’s book ‘England is Mine: Pop Life in Albion from Wilde to Goldie’ which tried to unravel the spirit of all this.

It’s not just film and TV and music culture either – it’s in the mad pottery of Portmeirion (Victorian apothecary pottery in buzzing colours), the luxuriantly moustached hussars on David Whitehead’s fabric, the lurid William Morris designs that fed into the pattern explosions of the 60s and 70s… this over-excited take on the ‘other’ side of Victoriana that’s the very opposite of the popular idea of ‘Victorian’. Even Beatrix Potter came to the party. You’ll never hear Wendy Craig reading The Tale of Jeremy Fisher and be the same again.

Thank you for the lovely and thoughtful comment! I haven’t heard of Michael Bracewell’s book but I’ll track it down! A.