Welcome to this year’s End of Year review; my usual, long-winded run-down of my excessive viewing and reading habits. It’s been an exhausting but rewarding year of films, television and books, and the sheer length of this post should evidence that.

One interesting thing to note is how much happier I feel having virtually ignored the majority of post-2010s culture. Such a decision was not taken lightly, perhaps even not really a decision at all but merely a trend in my general tastes that I’ve decided to fully embrace. It was during yet another visit to the house of Dennis Severs in East London this autumn, however, that the reality behind this possible decision became apparent.

American eccentric Severs lived and curated his own Georgian town house into a kind of fantasy museum of the past. While forgoing period accuracy, he achieved the kind of atmosphere that most historic properties would murder for. He got closer to the truth of eras past through a somewhat artificial image of their reality; it’s a deeply ironic scenario, but one I can now completely attest to. No one in the periods of culture I tend to focus on could watch these things in the same way I do (the ability to do so is mostly down to modern digital technology), but in doing so, I now feel much greater kinship with (and understanding of) said analogue age.

On looking out of the dusty windows of Severs’s house, as the wood creaked and the smell of wine and orange peel drifted in the air, the horrifying edifices of glass and steel surrounding Liverpool Street loomed into view. This feeling is essentially one I increasingly share on a cultural level. I’m lucky to live in a period which allows access to all of this older material, much of which feels of a more real and tangible world. Sometimes, more modern works do creep in through the net; a television show glimpsed while walking through the flat, reviews of the latest crap literary fiction, trailers for the newest digital nonsense in cinemas, the odd comission taken for cash. Little of it means much to me anymore and it’s a strange but wonderful kind of freedom to have.

I make no apology for any of this, and hope all of the work mentioned arouses curiosity: there’s a great deal here I would recommend.

Anyway, to the matter in hand.

Film

This year, according to the ever-forgetful IMDb (forgetful in the sense that it has a habit of removing ratings of mine on a whim), I’ve watched 223 films. Though the realities of living in my mid-thirties are starting to curtail the “one-film-per-day” dictum that I’ve tried to live by for the last fifteen years or so, there still appears to be plenty of decent films to watch, even if my eyes are starting to get a bit sore.

As with last year, this year has been dominated by classic Italian cinema. What’s more impressive is that few of the films that have hit home have been by the bigger name Italian directors (in a British context at least). In fact, some of weakest films watched this year have been by said bigger name directors; I’m still trying to forget my first, and only, viewing of Satyricon (1969), for example. Instead, it has been the Italian cinema that looked to the drama of crime and political corruption that really caught my eye.

My favourite was undoubtedly Francesco Rosi’s Hands Over the City (1963); an astonishing and gripping tale of dangerous, cheap redevelopments and corruption in Naples. Rod Steiger dominates as much as Rosi’s imposing way of shooting architecture (the majority of buildings appear as if they’re about to collapse upon the camera crew).

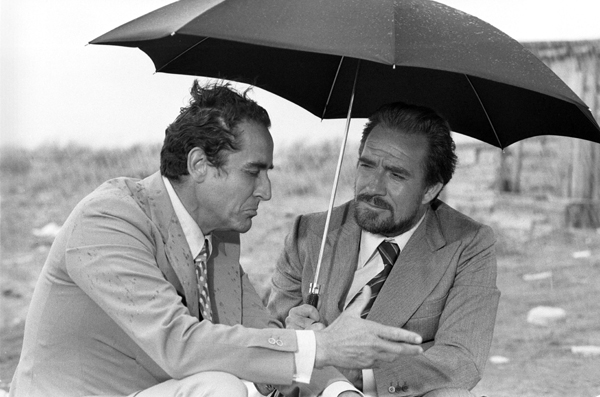

Rosi has actually been my favourite Italian discovery of the year, exploring his work after enjoying his The Mattei Affair (1972) last year. Alongside Hands Over the City, I also loved Salvatore Giuliano (1962) and The Swindlers (1961). Rosi’s ability to combine high artistry with (non-preachy) politics speaks volumes in an era when such similar dramatic abilities seem increasingly sparse.

Out of the remaining great Italian cinema I also enjoyed Dino Risi’s A Difficult Life (1961) and In the Name of the Italian People (1971), Pietro Germi’s The Facts of Murder (1959) and The Railroad Man (1956) and Ermanno Olmi’s The Fiances (1963).

This year’s gap-filling for classic British cinema has also been a joy with plenty of wonderful films finally ticked off the list. This is represented in my final ten in two very different films. The first is Basil Dearden’s emotional The Captive Heart (1946). Michael Redgrave’s performance may be my favourite of the year and, alongside watching Dearden’s Frieda (1947), it confirmed the director to be one of our best.

There was plenty of other British cinema from this general period that hit the mark, too. Henry Cass’s Last Holiday (1950) came close to vying for a position in my final ten, while I also enjoyed Carol Reed’s Laburnum Grove (1936), Clive Brook’s On Approval (1944), Harold Huth’s Nightbeat (1947), Daniel Birt’s The Interrupted Journey (1949) and Guy Green’s Tears for Simon (1956).

In terms of later British cinema, the most obvious stand-out was Bryan Forbes’s The Whisperers (1967). Its photography was beautiful, its location work breathtaking and its atmosphere chilling and lonely. I adored it, especially for Eric Portman’s caddish rogue appearing in the film’s third act. Equally, and in a similar vein it must be said, I also loved Jack Clayton’s Our Mother’s House (1967). With a likeness of atmosphere, almost Robert Aickman-esque even, and another caddish arrival in the third act (in the form of an Arthur Daley-ish Dirk Bogarde this time), it was a beautiful and haunting film. Just don’t research the modern reality of its ornate, Gothic Croydon locations; the developments sprouted in the intervening years are enough to chill the blood.

Finally, on a less serious note for British cinema, I did want to mention two other films. The first is Sidney Hayers’s musical Three Hats for Pamela (1965). While no doubt weak in parts, it brought a strange joy to see such a distinctly London-ish film, right down to Sid James jovially singing about knife fights in Lambeth. The other was the frankly brilliant North Sea Highjack (1980) by Andrew V. McLaglen. I accepted of late that I’ll watch anything with Roger Moore in (and I’ve enjoyed both The Sea Wolves (1980) and The Wild Geese (1978) by the same director in previous years as well), but this was a pleasure beyond expectation. I’d happily watch an endless film series of Moore as Ffolkes; the cat-loving, whiskey drinking, embroidery practising action man in tweed, firing snappy quips at James Mason’s dismayed naval commander. Utter bliss.

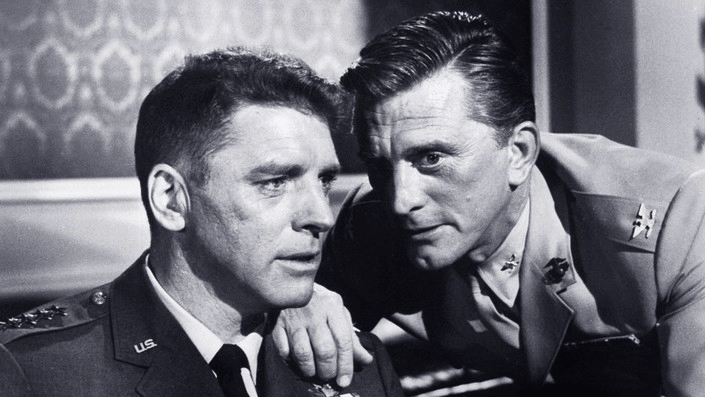

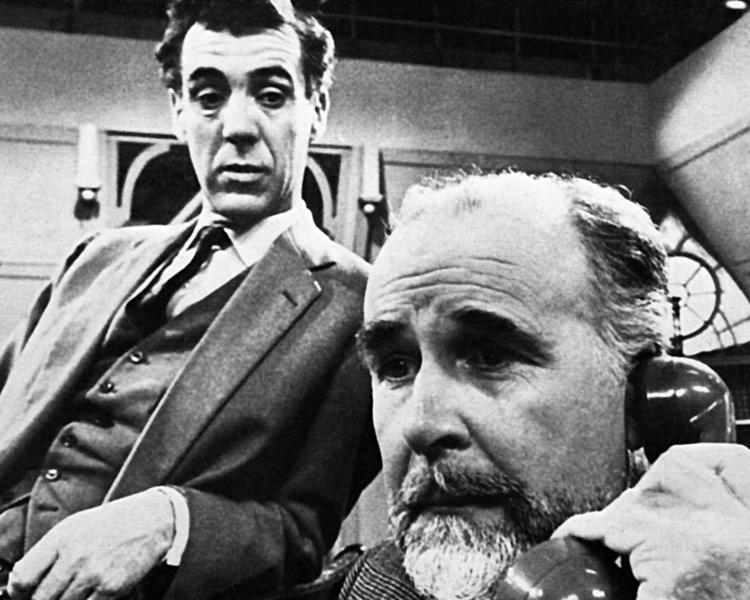

While I generally don’t order my final ten best films of the year, this year there was one undeniable stand-out: John Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May (1964). Its level of drama, batted between some of the best leads of American cinema (Lancaster, Douglas, March, Gardner), left me thrilled in a way no other film equalled. Even Frankenheimer’s other accomplished films watched this year – The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seconds (1966) – didn’t hit the spot in the way that this stunning political drama did.

Though few of the American films of this ilk reached the same heights, many were certainly very successful, enjoyable and worthy of further consideration. In fact, watching so many from the 1980s and 1990s, it reminded of how recent the relative demise of actual, no-compromise adult cinema in Hollywood has been (with a few exceptions still determinedly battling on, naturally). Films such Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict (1982), Peter Weir’s Witness (1985) and Wolfgang Petersen’s In the Line of Fire (1993) all reminded of a much stronger era of thrilling and nuanced popular cinema.

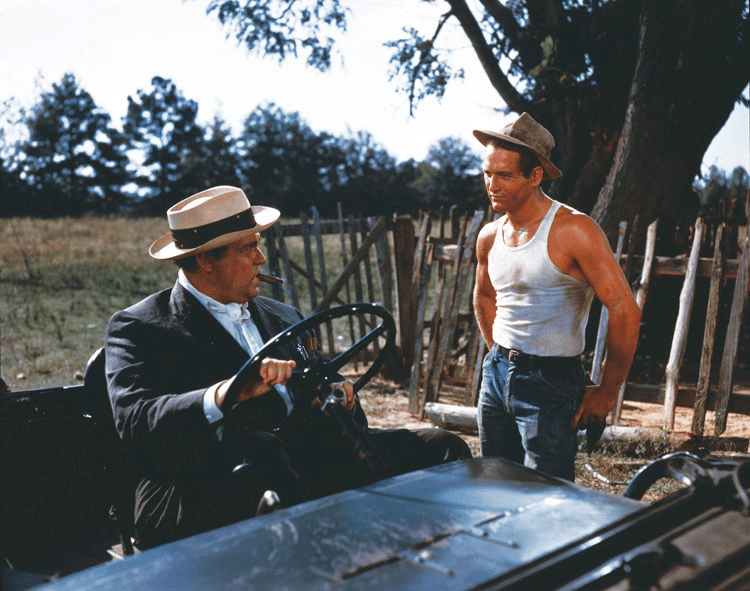

Adoring Paul Newman in Lumet’s film also meant I began diving into work of his that I hadn’t yet seen. The best of the viewing so far, aside from The Verdict, has been Martin Ritt’s The Long, Hot Summer (1958) and Richard Brooks’s Sweet Bird of Youth (1962). I look forward to watching more of Newman’s back catalogue in the New Year (though I’ve seen a fair bit of it already).

American genre cinema also provided some pleasure this year. It’s been a bit sparse for Westerns, though I really loved Henry King’s The Bravados (1958) and Robert Wise’s Tribute to a Bad Man (1956). The same can also be said for War, with the only film to really consider mentioning in hindsight being Don Siegel’s underrated Hell is for Heroes (1962). The best documentary watched this year was also American: Sheldon Renan’s The Killing of America (1981). I’m not sure I could sit through its shocking mixture of alarming footage and depressive thesis again (it made Adam Curtis’s films look jolly by comparison), though most of the era’s current problems (especially in cities) are basically diagnosed effectively here forty years earlier. This one is, as an aside, not for the squeamish.

If the true crime of Renan’s film was too much to bear at times, the same cannot be said for fictional crime. American noir was, as ever, sublime. One made it into my final ten in the form of Lewis Allen’s tense and brilliant Suddenly (1954). Featuring what must surely be Frank Sinatra’s best screen role, its quiet set-up and strangely claustrophobic drama of political assassination made for compelling viewing.

Some other noirs almost scraped into my final ten as well, this year being stronger than the last few. Films such as Alfred L. Werker’s Repeat Performance (1947), Anthony Mann’s T-Men (1947) and Side Street (1949), Joseph Pevney’s Undercover Girl (1950), Harold Daniels’s Roadblock (1951), Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper (1952), Arnold Laven’s Vice Squad (1953), Nunnally Johnson’s Black Widow (1954) and Robert Mulligan’s The Nickel Ride (1974) are all deserving of high praise.

Moving on from America, I was surprised by how much decent French cinema I managed to view this year. Having hyper-focussed on it for quite a while, I was under the impression that most of the great stuff had been watched. How wrong I was. Costa-Gavras continued his one-man mission to please me with Special Section (1975); a powerful drama about Vichy Government machinations. I can’t quite remember the last time a film of his didn’t make my end of year rounds, so I’d better start savouring what I’ve got left of his to watch.

The other French inclusion in my final ten was an Italian co-production: Valerio Zurlini’s The Desert of the Tartars (1976). It’s a genuinely difficult film to describe; such is its strange, shifting atmosphere, almost feeling supernatural at times in its display of paranoia in a Bastiani fortress soon to be attacked. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Phillipe Noiret show off their usual, dependable brilliance.

Other great French films watched included François Reichenbach’s America as Seen by a Frenchman (1960), Henri Colpi and Jasmine Chasney’s The Long Absence (1961), Christian-Jaque’s Don’t Tempt the Devil (1963) – Bourvil’s serious roles are always fantastic – Robert Hossein’s The Secret Killer (1965), Édouard Molinaro’s Oscar (1967) – easily the (intentionally) funniest film watched this year – Michelle Porte’s Les Lieux de Marguerite Duras (1976) and Yves Boisset’s The Woman Cop (1980).

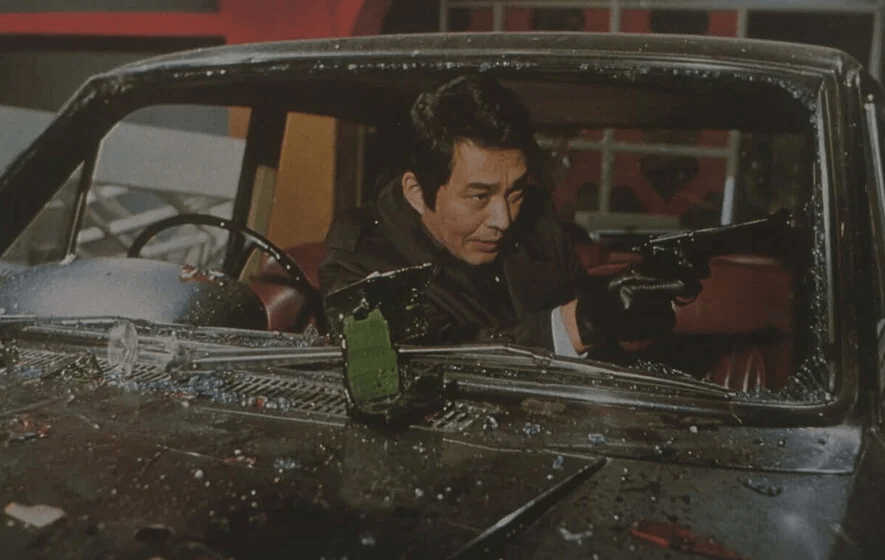

The other great national cinema I’ve dived into this year is that of Japan. This, however, didn’t manifest in quite the way I expected. I imagined I’d be listing an array of excellent samurai films ticked off at the end of the year but the only one worth mentioning is Hideo Gosha’s relentless Hunter in the Dark (1979). Equally, aside from ticking off a few remaining Ozu’s, there was little that was really classically canonical in my viewing. Instead Japan’s cinema soared for me in its genre and Yakuza films. Gosha actually began my viewing in this vein with the excellent Violent Streets (1974), but this was only the tip of the iceberg.

This trend is represented in my final ten with the enjoyably overblown Sympathy for the Underdog (1971) by Kinji Fukasaku. Really, I could have chosen any number of other Japanese films to slot in. I haven’t, for example, stopped thinking about Shôhei Imamura’s Vengeance is Mine (1979); one of the grimmest crime films I’ve ever watched. However, I was less impressed with Imamura’s highly respected A Man Vanishes (1967) or Pigs and Battleships (1961); again suggesting an ambivalence to more canonical works. It was the pulpier equivalents that I found more rewarding. A film such as Yasuzô Masumura’s Black Statement Book (1963) ticked more of my boxes.

However, this was the year I properly dived into the work of Seijin Suzuki. Having only watched Branded to Kill (1967) before (and finding it OK at best), I was unsure what to expect. What I got was a wealth of hyperactive, complex crime cinema of the best kind. So much style, so much double-dealing; they became addictive. Films like The Sleeping Beast Within (1960), Everything Goes Wrong (1960), Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards! (1963), Youth of the Beast (1963) and, of course, Tokyo Drifter (1966), marked a high-watermark of the year’s viewing and I’d have likely chucked a few of them into my final ten if not restraining myself.

Finally, the year’s viewing wouldn’t be complete without a collection of hilariously bad films to space out the more serious viewings. My favourite of these was undoubtedly the ridiculous Megaforce (1982) by Hal Needham; a film so camp it should come with a health warning. However, Needham was far from alone in providing the year’s enjoyable awfulness. I had great fun with Luigi Cozzi’s Starcrash (1978) and Hercules (1983) – a director I incidentally met on a trip to Rome earlier in the year and, it must be said, is lovely – Larry Buchanan’s The Loch Ness Horror (1982), Woo-sang Pak and Y.K. Kim’s Miami Connection (1987), Rick Sloane’s Hobgoblins (1988) and Amir Shervan’s Samurai Cop (1991). I don’t think I’ll ever forget the image of Robert Z’Dar’s ever-changing head of thick, bizarre hair. Ever.

Literature

As with my film viewing, this year I began by ticking off some of Italian crime’s best known (and available in translation) novels. Unlike their film equivalents, however, they paled in comparison. The main bulk of reading in this regard was taken up by Carlo Lucarelli’s De Luca trilogy, namely Via delle Oche (1996), The Damned Season (1991) and Carte Blanche (1990). The whole set-up, with De Luca being a detective working through the difficult period of the fall of Mussolini’s fascism, should have made for some incredibly complex crime novels but only The Damned Season really found its mark. Unlike in my other reading, these were books that I felt needed to be much, much longer.

Uncertain about Lucarelli, I decided to go back to the work of Leonardo Sciascia. However, this didn’t quite go according to plan. I began with his write-up of the assassination of the Italian prime minister Aldo Moro by hard left terrorists, The Moro Affair (1978). Having watched a huge number of films inspired by similar events during the Years of Lead, I thought this would be a great place to start. It ended up being one of the most confused and baffling books I read this year; resulting in putting Sciascia away again to ponder until the New Year. I hope some of his fiction will correct the average streak I’ve unfortunately ran into with his work thus far.

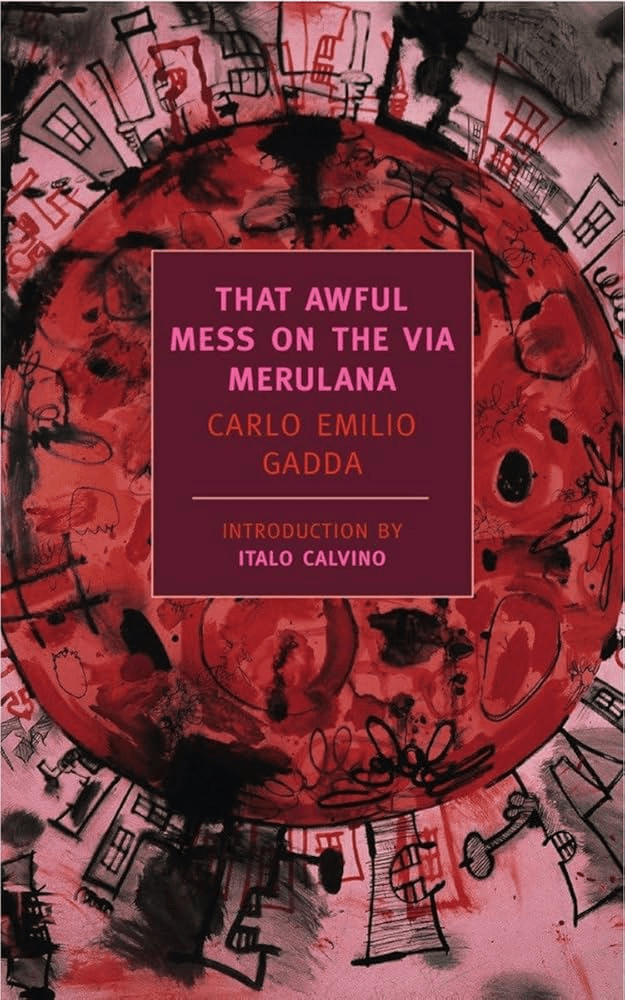

Finally, I thought I’d try the big guns: Carlo Emilio Gadda’s That Awful Mess on the Via Merulana (1957). The book has praise from just about every Italian intellectual going, some describing it as Italy’s equivalent to Ulysses, others suggesting it to be the height of Italian crime literature. It seemed to be neither, and again was a sprawling mess with a good novel struggling to escape the intellectual excesses of its period and politics. Ironically, its previously mentioned film adaptation The Facts of Murder (1959) was utterly superior in every way.

Not deterred by this rather unfortunate streak of reading, I went much further back in Italian literature and was, naturally, not disappointed. This was finally the year that I read Dante’s The Divine Comedy (1320) and it was really beyond words. Trying to summarise it here is obviously difficult but the level of language, idea, form and sheer beauty defies further description. A truly towering work of human achievement. I haven’t included it in my final ten simply because it feels inadequate to assess it in such a way. Equally, I loved Vasari’s chatty The Lives of the Artists (1550) a detailed account of essentially the greatest artists who’ve ever lived; its descriptions of the paintings alone verging on heady experiences of the transcendent.

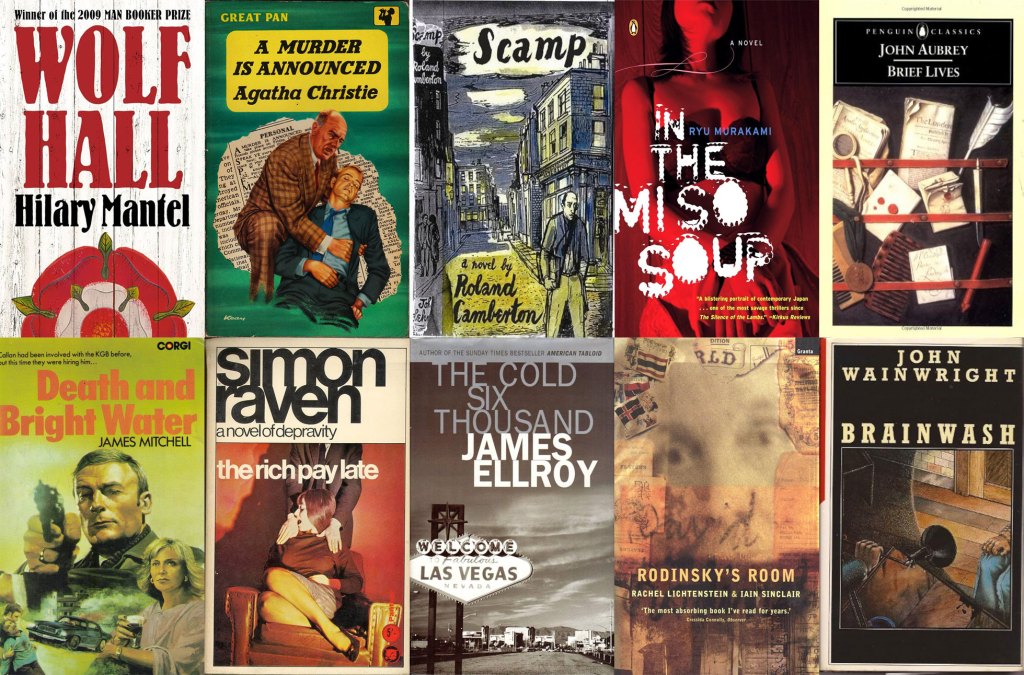

The national cinemas that I explored didn’t quite deliver the same volume of great literature as their screen cousins. In my top ten, Japan is represented once with Ryū Murakami’s disturbing and brilliant In the Miso Soup (1997); a kind of neo-noir meets American Psycho fable filled with horrifyingly lingering images as well as a biting critique of tourism and the effects it has on a city. I also largely stayed away from French literature this year, too, with only a single Maigret (and the lazy Burglar, 1961) by Georges Simenon being read.

American crime was relatively strong, if not too deeply explored. James Ellroy continued to astound with the follow-up to American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand (2001). It was as relentless and grim as its predecessor and I drank down its nastiness quickly and enjoyably. I also started my follow-up of the work of Elmore Leonard in the form of Rum Punch (1992). Another twisting moral tale of a decayed America, it’s surprising how much stronger it works on the page than on screen (in the form of Jackie Brown).

Where the standard was really high in this year’s reading was British literature. In fact, all sorts of British writers of various kinds have surprised, astounded and entertained me. I should really begin with my favourite discovery of the year: Simon Raven.

I began his famed Alms for Oblivion series with the deliciously back-stabbing The Rich Pay Late (1964). The prose flowed by while the corruption on show was as good as any I’ve seen by fully fledged crime writers. I actually started my Raven reading with his stand-alone novel Close of Play (1969) which again had disreputable characters using each other in a wonderfully 1960s fashion. At the time of writing, I’m actually reading Raven’s non-fiction about English gentlemen, but you’ll have to wait until next year to hear my thoughts on that and no doubt many other books I plan to read by this brilliant author.

Most of my year’s best books have been concerned with this kind of atmosphere: down and out, post-war grit of various kinds. James Mitchell, a regular of my best of year round-ups, was again present in the form of Callan’s adventure in Death and Bright Water (1974); a more jet-setting tale for the usually London-bound killer. It took a while to find it but Roland Camberton’s Scamp (1950) – a desperate story of seedy dealings in bohemian Soho – was well worth the wait, and I finally started reading the work of underrated Yorkshire crime author John Wainwright as well. His novel Brainwash (1979) is just as good as the later French film adaptation (Claude Miller’s The Grilling (1981)). I should also mention Derek Raymond/Robin Cook’s The Tenants of Dirt Street (1971) which started off a little patchy but grew magnificently as it went on.

Classic crime and adventure certainly ticked a good few boxes this year. The snobbery around Agatha Christie never ceases to surprise me and, reading A Murder is Announced (1950) – one of my highlights of the year – reinforced that sentiment yet again. The intricacy of her narratives, the interrelations between her characters and the sheer readability of it all is nothing short of miraculous. It should be considered one of the great mysteries as to how she did it so regularly and in such volume. It just doesn’t seem humanly possible. What a genius she was.

Another classic I began to get to greater grips with was Conan Doyle’s Holmes. I’ve read a fair bit of Holmes over the years but this year I finally began to concentrate on it, just to make sure that I’ll be, at some point, totally up-to-date with his adventures. This year I read two contrasting volumes of shorts: The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893) and The Case-book of Sherlock Holmes (1927). Both were filled with gems and make for perfect autumn reading in particular.

Not everything in the adventure vein hit the mark, however. I mildly enjoyed John Buchan’s slim The 39 Steps (1915) but a few aspects dated it in a way that its screen adaptations happily avoided (namely a latent anti-Semitism); Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda (1894) should have been a swift read but its narrative was fogged by a strangely haphazard prose; and C.S. Forester’s The African Queen (1935) was perfectly fine but nothing more.

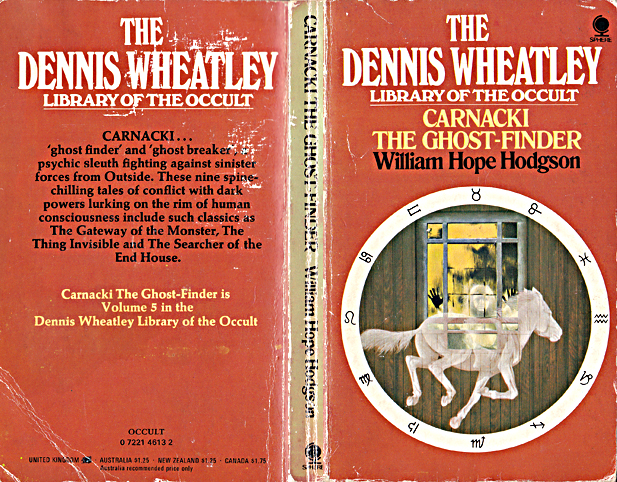

Strangely, my other dive into general genre fiction has been incredibly hit-and-miss this year. I started 2024 by reading W.H. Hodgson’s Carnacki, the Ghost Finder (1913) which was fantastic, and ended the year with his novel The House on the Borderland (1908) which, frankly, was not. Equally, I enjoyed Susan Cooper’s Greenwitch (1974) but less so the opening novel of Cooper’s Dark is Rising sequence, Over Sea, Under Stone (1965). Even the ghost stories of Edith Wharton (in the NYRB volume Ghosts (1937)) and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Threshold (1980) felt rather lacklustre compared to previous works read by both authors.

It was at this point in my reading that I took a leftfield turn and dived into non-fiction.

My year’s best book was undoubtedly John Aubrey’s Brief Lives. These short portraits of historical persona, famous and not-so-famous, were addictive from beginning to end, written in a beautifully collapsing Early Modern English and filled with gossipy detail. Some of the information brought me to tears of laughter, such was its bizarre and blunt delivery, and the book has certainly influenced a future book project of my own.

These kinds of historic, ethnographic portraits became a growing reading pleasure throughout the year. I finally read Ronald Blythe’s wonderful (yet surprisingly grim) Akenfield (1969) after (appropriately) picking it up from a book box in Suffolk, while I devoured Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (1136) which filled a range of gaps in my knowledge of the sort of figures often cropping up in more modern works that have interested me over the years (King Penda etc.).

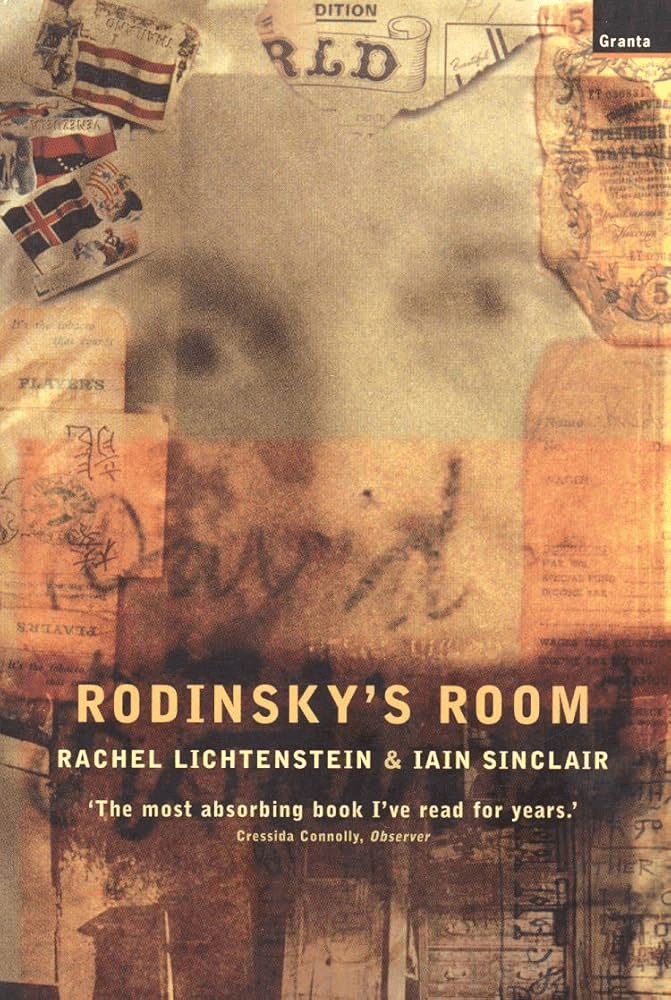

The other great non-fiction to make my final ten was Rachel Lichtenstein and Iain Sinclair’s Rodinsky’s Room (1999). Litchenstein’s story of Rodinsky and its inevitable strands of Jewish history was haunting, while Sinclair’s usual framing of his favoured cultural figures was like returning to an old friend still chattering away at the back of the pub; Emanuel Litvinof, Hawksmoor, Jolly Jack, Krays et al.

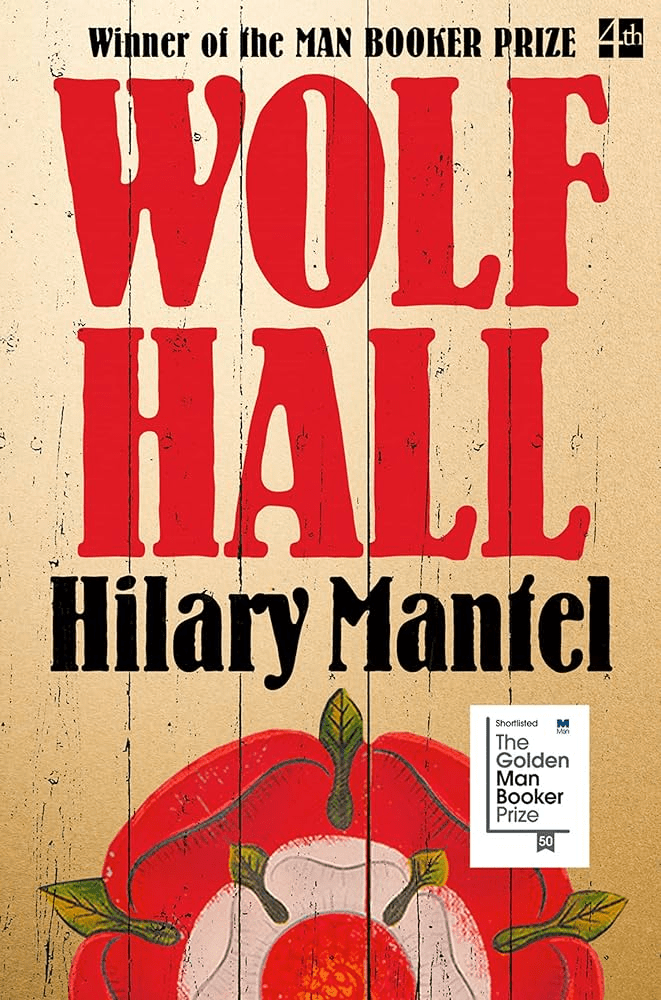

Finally, two wonderful British novels are worth mentioning, though one just missed out on my final ten. The first, which did make it in, was Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (2009). While deeply suspicious of the kind of books that get the sort of wall-to-wall PR treatment from the British publishing industry, Mantel feels one of the few that fully deserved the big wall spread in Foyles and the window displays in Waterstones. I can add little that hasn’t already been said of her, except that, when she died, British fiction lost one of the few voices generally worthy of the excitable hype machine the industry desperately deploys to keep business afloat in an age of increasing, celebrated mediocrity.

The other novel to mention is Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945). I had great fun with Scoop (1938), but Brideshead was a distinctly different, more patient affair. Every element was so measured and precise, so adept in its array of melancholia even, that it haunted me for weeks after reading; not simply in its sad tale of times between the wars, but in the sense that I wondered if I was going to read anything that could match it. Luckily for me, I read precisely ten books that did, but it was a wonderful work all the same.

Television

Unlike my film viewing this year, older television has been maintained at a high rate. In fact, I think I’ve watched more series and drama than in any other year, and certainly all of the shows mentioned here have been watched in their entirety.

My viewing year started with exploring the work of scriptwriter Francis Durbridge. One of his many serialised dramas for the BBC made it into my final ten in the form of A Game of Murder (1966). The drama gave Gerald Harper (a personal favourite) a chance to shine in an early leading role. Essentially, the set-up of suburban epsionage/crime machinations was Durbridge’s metier, with virtually every other drama I watched by him doing similar things, albeit always with superb casts. Whether a very young John Thaw leading Bat out of Hell (1967), Peter Barkworth in Melissa (1964) or John Fraser in The Doll (1976), the drama was always fun and twisting, even if it did seem to amusingly paint the country lanes of the Home Counties as being a thriving hotbed of spies. My real favourite in hindsight was probably A Man Called Harry Brent (1965) which featured Harper again, this time having a silky-voice showdown with the wonderful Edward Brayshaw.

Getting a taste once again for the criminal elements briefly present in Dubridge’s dramas, I began trying to find straighter crime series to satisfy my needs. The strongest was undeniably a little-discussed London Weekend Television series called The Gold Robbers (1969). Featuring a huge cast, Peter Vaughan’s detective is charged with tracking down a brutal, crack team of criminals responsible for a surprisingly violent gold robbery from an airport. The way the drama manages to anthologise its story into many different types of episode (from vast chases to intricate psychodramas) was spellbinding (similar in a way to the later Villains).

Another London Weekend Television show I spent a good deal of time working my way through was New Scotland Yard (1972-74). Though it occasionally dipped in quality (in a way that the two series of Softly, Softly: Task Force watched so far admittedly hasn’t), I came to enjoy my daily rounds with John Woodvine as Detective Kingdom and the slimy but watchable John Carlisle as Ward. The final of the four series lost these leads, and it certainly lost something with them, though the quality of the stories was largely maintained to its conclusion.

On the other side of the law, I finally watched Budgie (1971-72), another LWT show. How on earth did they do it? I wasn’t sure what to expect from this series, showing the grubbing around of cockneys making a dishonest living in 1970s Soho, but it certainly bucked expectations. Adam Faith deserves an Oscar for his utter commitment to the role of Budgie, the villainous mixer and fixer, and, of course, Iain Cuthbertson as the terrifying gangster Mr Endell. Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall’s creation fizzed off the screen, though its role as a comedy is moot; in fact, the unintentional period nastiness (including the alarming storyline of Budgie selling his newborn child to a stripper for ready cash) actually added to the drama rather than detracted from it. This one has been especially surprising to talk to people of a certain age about, such was its cultural impact (even my mother’s partner from Bury said “Leave it aaout” in Faith’s cockney accent and “Budgieee…” in Cutherberton’s alarming Scottish tones at its mere mention).

Thankfully, the criminal element was kept well in check in my viewing thanks to an array of excellent private detectives. In fact, private eyes make up a fair chunk of my best viewing of the year. At one end of the spectrum, there was Granada’s Mr Rose (1967-68). The third and final series featuring William Mervyn’s wonderful Chief Inspector Rose (here simply “Mr” and retired to Eastbourne), the series was the strongest for the character (of what survives…) and made for warm and witty viewing.

At the other end of the detective spectrum, I watched two great 1980s investigators. The first was Trevor Eve’s Eddie Shoestring in Shoestring (1979-80). An enjoyably ramshackle, alternative detective, Shoestring’s West Country investigations ventured into some surprising and refreshing territory, whilst also managing to cover the issue of mental health in a non-simplistic and shoehorned manner. The second was the ever reliable Don Henderson as Bulman in Bulman (1985-87). Having loved him in The XYY Man (1976-77) but being uncertain of him throughout the run of Strangers (1978-82), the series could have gone either way. Like Mr Rose, third time was definitely the charm and the series had that lovely old, run-down London feel that some 1980s British series manage to take advantage of when it’s on tap.

My favourite series of the year didn’t concern any crime whatsoever, but simply high-end business negotiations (which may constitute the same thing depending on your point of view). This may be a hang-up from loving the short series The Organization (1972) last year but this year’s best viewing was undoubtedly The Power Game (1965-69). Featuring a battle of organisational power between Patrick Wymark’s bullish Wilder, Clifford Evans’s Caswell Bligh, Peter Barkworth’s Bligh Jnr, and Jack Watling’s Henderson, the series was essentially what a soap opera by Harold Pinter would have looked like; all jet-setting power-grabs, back-stabbing deals and manipulative affairs. I look forward to watching its predecessor The Plane Makers (1963-65) in the New Year.

In a similar vein, I very much enjoyed The Main Chance (1969-75). Rather like Wymark’s Wilder, John Stride’s high-flying lawyer David Main was a force to be reckoned with on screen. Lines of legal jargon are fired out with machine-gun speed and brutality, and the general pace of the series was exhilarating. If you like your period style and general street furniture of the early 1970s in particular, this series will be doubly pleasurable.

One of the more hit-and-miss elements of my viewing has been filling in some of the gaps in my genre anthology series. My favourite was undeniably Orson Welles Great Mysteries (1973-74) which managed to be pretty consistent and enjoyable. However, the same could not be said for others. I watched the entirety of Tales of the Unexpected (1979-88) and found there to be roughly one good episode per ten (which, for a series of 112 episodes, isn’t very good). Its adaptation of Elizabeth Taylor’s The Flypaper is still its undeniable gem. Equally, I found Tales of Unease (1970), Chiller (1995) and The Mind Beyond (1976) strand of BBC 2 Playhouse to all be pretty lacklustre, with only one or two stories from each hitting the mark (especially The Mind Beyond episode, The Stones).

Literary adaptations seemed far more stable and reliable. I was very close to putting the BBC adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1979) in my final ten, such was power of Joanna David and Jeremy Brett’s performances. Brett also astounded as D’Artagnan in the BBC’s The Three Musketeers (1966), more than holding his own against, among others, Brian Blessed. However, the series lost something when he was replaced by Joss Akland for the follow-up, The Further Adventures of the Four Musketeers (1967), though that series compensated by having the excellent Michael Gothard as one of its villains.

In terms of other literary and literary-adjacent adaptations, I also enjoyed the BBC’s Barnaby Rudge (1958) and Bleak House (1959) – though Colin Jeavons’s decent performance shows what a wet fish the character of Richard Carstone is in the latter – The Hound of the Baskervilles (1983) – both of Ian Richardson’s turns as Holmes show him to be perfectly suited to the role, unlike Tom Baker whose 1982 Hound I also watched, with much enjoyment at its ridiculousness – and the strange but fun drama Dr Watson and the Dark Water Hall Mystery (1974) following Edward Fox’s Doctor Watson on an unusual side-quest.

Not everything in archive television is guaranteed to be great, and having watched a lot this year, plenty fell short of the mark. I finished The Man in Room 17 (1965-66) and moved on to The Fellows (1967) which was indulgent nonsense (interesting only in it tying in to the same universe as Robin Chapman’s other, superior series Spindoe); The Mind of J.G. Reeder (1969-71) had potential but was made unbearable by poor pacing, dodgy George Formby-ish music and period trappings; Spyder’s Web (1972) didn’t know what sort of series it wanted to be (though it was nice to see a young Anthony Ainley relishing an evil role); Hannay (1988) started off well but quickly lost its way among the nostalgia; and Artemis 81 (1981) was an incomprehensible mess (though David Rudkin’s Gawain and the Green Knight (1991) was fun).

I also accepted that the high-end ITC style series, while being something I do enjoy, can’t be binged in quite the same way as multi-camera television. Gideon’s Way (1964-66) was a good example in that I craved a few wobbly sets and video work as it was just too pristine and stilted. Shorter series like Strange Report (1969-71) and The Zoo Gang (1974) were more fun. The former is frothy, Swinging Sixties nonsense but Chester’s finest Anthony Quayle became one of my go-to style inspirations. The latter has great theme music by Wings and some nice, actual location filming in a proper jet-setting locale (something usually faked in such series). I also finally finished The Saint (1962-69). Having another go-to style inspiration in Roger Moore, I got into a routine of watching an episode as I got ready for various dates (something I thankfully don’t have to do anymore, though I’ll always look to Roger for inspiration for a future night out with my partner). The weakest of these high-end series was the short-lived Pathfinders (1972) but its failure brings me to my final TV highlight of the year.

Looking to fill a gap left by last year’s Secret Army (1977-79), I searched for another long-running war drama to watch throughout November. The series eventually chosen was Rex Firkin’s Manhunt (1970). While having some flaws in comparison to Secret Army (Cyd Hayman’s character bearing the brunt of such flaws, including being brought out of a mental collapse by a good seeing to from a Frenchman), the series was still brilliant. Each episode dealt with an entirely different aspect of the three leads (Hayman, Peter Barkworth and Alfred Lynch) on the run through occupied France; from an entirely dialogue-less sabotage episode to hard-hitting interrogation two-handers. Philip Madoc and Robert Hardy made for great, complex villains as well. Its episode featuring Julian Glover as a British fascist may be one of the strongest dramas I’ve watched this year, and television as a whole has kept me sane more than anything else in 2024.

My Work

Having had a quiet 2023, I promised myself I’d say yes to everything and anything offered work-wise this year. This has meant quite a bizarre and rewarding array of work. I’ve chatted on Radio 3 about The Conversation, I’ve appeared on camera for documentaries about Doctor Who (for the upcoming Season 7 blu-ray set as it happens), I’ve chatted about witch-hunts and Westerns for other Blu-ray extras, about ghosts and cathedrals on stage at cinemas, Sir Gawain in an art gallery and Hauntology to viewers in America. Most importantly, I’ve travelled to more film locations for the British Film Institute than I’ve ever done in my life (in fact, so many that it was almost a weekly thing, seeing everywhere from Berlin to Brixton, via Rome, Vienna and Oxford).

Five articles I’m happy with are below.

Sight & Sound: Lost & Found – The Grilling

BBC: The Leopold & Lobe Case with Patrick Hamilton and Hitchcock

BFI: Dario Argento’s Museum of Horrors

BBC: The Surveillance of The Conversation

BFI: Five Locations from The Third Man

In regards to longer term projects, I’ve been drafting a number of things, most of which I can’t actually talk about yet. I’ve had my first audio drama commissioned, drafted and recorded in studio, though it won’t be released until 2028 so more on that in – checks notes – three years. I’ve also been serialising a book project for my own website called Presence, the ongoing chapters of which can be read in the link.

Lastly, and most importantly, I have a new book coming out. In fact, there may be several but we’ll see how it goes. Local Haunts (2025) is going to be published by Influx Press. The volume collects (and edits…) a huge body of my non-fiction work over the last decade dealing with film, literature and TV that explores place and landscape as a theme. I’ll no doubt be talking more about that in 2025, but it was a lovely way to end the year.

Many thanks to my readers and wishing everyone a lovely 2025.

Onwards.