My second memory concerning a Polaroid photo appearing in pop culture was one taken by a maniac. This maniac had hitched a ride from some naïve teenagers in the sweltering outback of Texas and was freaking them out with his variety of macabre hobbies. He’d just visited the local slaughterhouse before they picked him up.

He didn’t work there. He just liked it.

His Polaroid camera dangled around his neck as he jumped into the van along with an assortment of other strange objects. As the travellers talked to the hitchhiker, he pulled out a purse made from roughly cut animal skin and fur, inside of which he kept his precious Polaroids folded up and well pawed. He clearly spent his time admiring them.

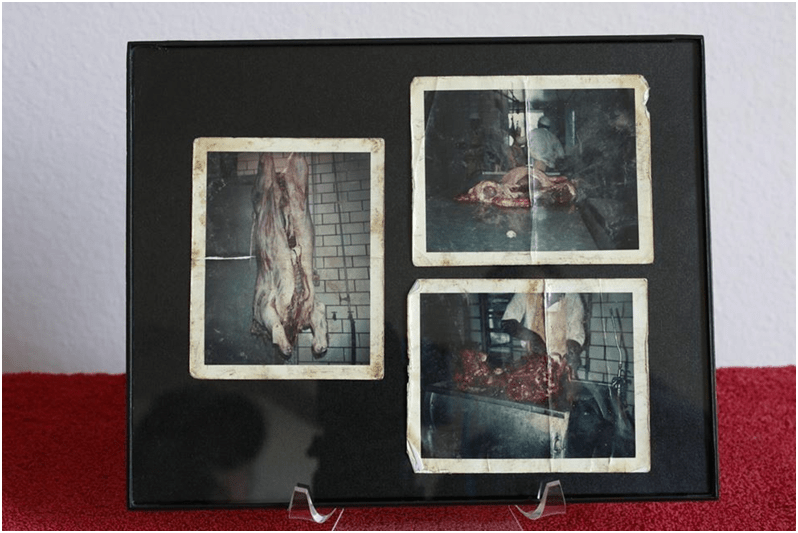

He shows the images excitedly to the travellers and they are unnerved by what they see. The photos are greasy, grimy shots of inside the slaughterhouse: flesh and bone hanging in front of tiled, wipe-clean walls. They fail to recognise this as a grim omen of things to come for their own road trip.

The scene is from Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and, alongside the noted chainsaw that gave the film its evocative title, the Polaroid camera plays an important role in the film’s grim exploration of technology and industry.

I love this strange scene for several reasons, most of which connect to the ominous qualities of the Polaroid. The character of the hitchhiker, played with committed oddness by Edwin Neal, is entranced by both his camera and the decaying bodies of the dead (animals and humans) he’s caught with it. The camera seems magical to him though this is hardly surprising considering he’s a man who enjoys spending time in slaughterhouses and making bizarre sculptures in local graveyards using the bodies, bones and skin he unearths from the arid Texan ground.

His perception of the camera as something profound is not, however, positive. Soon he is performing a bizarre ritual with it. He slices his own hand with the knife of one of the travellers to test its quality and, as the blood runs thickly between his fingers, he sets up his camera and waves it around, looking threateningly through the lens as he decides who to point it towards. He takes a picture of Franklin (Paul A. Partain), the wheelchair bound grump of the group who will soon have a chainsaw ploughed through him. Even if not knowing that the film is one of the archetype “final girl” narratives – horror films where one female character is left standing out of a group – the viewer will be aware that Franklin in particular is in trouble from this moment on.

The hitchhiker peels the Polaroid from its disposable cover and looks excited to the point of orgasm. The pleasure of seeing the image and reality side-by-side is spread all over his face. Its strangeness takes over momentarily and he hands it over with bloodied astonishment to Franklin so that he can admire his own image, as if this was something special and not a common occurrence. The man is wary. He now slots in nicely with the hitchhiker’s motley collection of deathly, grotesque Polaroids. Is his body soon to be just another piece of hanging meat in some anonymous Texan slaughterhouse?

The short answer is yes, and he seems unconsciously aware of it. He tries to disassociate from the Polaroid: it’s not a good likeness. ‘It hasn’t come out well,’ he argues. He may as well have had his fortune cast, attempting half-heartedly to deny its predictions. He gives the Polaroid back before the hitchhiker begins to argue. It’s a good photo and Franklin owes him money for the privilege of the image. He won’t get his few dollars.

In an even more unusual move the hitchhiker takes some tinfoil from his animal bag and meticulously unwraps it. The others watch with apprehension, sweat dripping in the backwater heat. It looks like he’s preparing a well managed drug habit and, as this is the era of the counter-culture’s souring, it wouldn’t be too fantastical if he had such inclinations.

He drops the Polaroid onto the shining material before proceeding to light some sort of combustible, sacrificing the image. The photograph sparks and burns loudly, causing chaos as the van’s other occupants panic. The madman enjoys the moment, before taking a knife to Franklin’s arm and jumping out. He runs after the group, wiping the blood from his own wound on the window.

The ritual is complete. He has cursed the van’s occupants with his Polaroid liturgy.

They don’t stand a chance.

In the trailer for the film, the sound of the Polaroid takes precedence over the growling of the chainsaw wielded by Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen), the monstrous henchman of the film. It’s not the typical sound of a Polaroid admittedly but still recognisably the click of its flash before an unbearably scratching squeal, one of the film’s genuinely horrifying and effective elements (its violence, in spite of its reputation, is surprisingly tame compared to later horror cinema).

The Polaroid and the chainsaw represent the duality of the film’s horror: two different, deeply human endeavours – working and creating – demented and twisted into the most depraved of cul-de-sacs. On the one hand, the chainsaw is a tool for work, the family at the film’s heart simply recreating the slaughterhouse that the hitchhiker enjoyed spending time in, only preparing the meat of travellers’ bodies to sell at the local highway pit-stop instead.

The Polaroid on the other hand represents a creative endeavour, one of documenting. We see quite a few of the devilish but undeniably creative objects made by the family – dead-skin lampshades, bony chairs, bizarre corpse sculptures – in the film’s trailer lit up by the Polaroid’s flash. The horror within the Polaroid’s presence here is one of pure, grimy aversion. Even in bizarre toys available in line with the film, the hitchhiker character comes with a tiny version of the camera as well as his trusty flick-knife.

Fittingly, I came across versions of the Polaroids from the film online when searching for general Polaroids from 1970s America. They weren’t the originals – this wouldn’t be possible for the one of Franklin as it was burned in the hitchhiker’s ritual – but instead reproduction props available to buy from a company on eBay.

To see the images taken in the film by the hitchhiker come up quite naturally alongside images from noted (and real) photographers spoke of the strange qualities that Polaroids obtain. Even the fake ones are interesting.

The seller had two lots for sale. The first was of three that were meant to be from the slaughterhouse. The other was of Franklin, allowing for a potential continuity error to slip into reality itself. The reproduction of Franklin interestingly has its boarder marked and grimy as if it had been to the slaughterhouse with the other photos; ominous stains covering its casing and frame.

The point in telling of the hitchhiker’s Polaroids is to highlight their unusual presence in the world of crime, real and fictional. This particular criminal scenario is a far cry from those unnervingly quiet urban dwellings that Dennis Hopper insinuated in his Polaroids. The irony is worth noting, however, that Hopper himself would eventually play the detective in Hooper’s sequel The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), searching for the murderers of the teens from the original film as he plays Franklin’s uncle, the man in the hitchhiker’s Polaroid.

Either way, Polaroids seem associated with crime scenes and criminality in general, even if in this film they seem to foreshadow what is to come rather than act as evidence of what has already happened. Crime scenes themselves, in reality and in fiction, seem lit within the imagination by a flash firing upon unspeakable atrocities. Crime scene photography is itself a complex expression of the medium, both in what is captured and how they are viewed – strictly purposeful and with a specific set of limitations yet undeniably captivating and interesting to look at.

The Polaroid, when used in this context, becomes tainted by death’s presence.

If we consider crime photography as a creative rather than perfunctory form, the first name that comes to mind is the noted American photographer Weegee. Weegee himself seemed like a character straight out of a hardboiled novel. If he was a book with a cover, it would be black & yellow with well thumbed pages. He was an artist preoccupied with the darker side of New York City, relentless in his search for its brutal rather than picturesque reality. Death was undeniably fascinating to him.

‘People are so wonderful that a photographer has only to wait for that breathless moment to capture what he wants on film,’ he once said and he was right on more than one front. The moments he caught were more often than not breathless because the subjects were dead; whether stabbed, shot or already on the slab downtown.

It may be unusual to consider Weegee in the context of Polaroids, simply because he never took any. He worked explicitly on grainy black & white images and even admitted that his work occurred as much in the developing room as on the street. Today, Weegee’s crime scene photographs still have the ability to shock, as if actually taken by a murderer, so fresh are the corpses, so unyielding is his stare. But the point in raising Weegee’s work is to simply be thankful that he didn’t use a Polaroid camera. Images of worlds such as his would have been utterly unbearable to consider with that camera’s unsparing gaze.

Polaroids of similar subjects do, of course, exist, made in the era when Polaroids took over the role of other forms of photography, held in crime files held by the police. It’s a cliché of crime fiction after the era of instant photography to have a Polaroid capturing a crime scene. In film and television, the sound and sight of its flash is often the first thing we see and hear of drama surrounding crime scenes, regularly used as a grammatical device to segue into the scenario in question.

Like the hitchhiker’s Polaroids and Dennis Hopper’s, there’s something unnerving about the object in question being in such close proximity to death and its grisly entrails. While Weegee’s photos were effective because of the atmosphere and underworld they undoubtedly exude, they do not possess the same presence as a crime scene Polaroid because Weegee’s came into proper, meticulous existence in his workshop. In any case, Weegee regularly characterised himself as a hustler, and the fact of him being there was enough to ensure his brilliant photographs lasted in the decades since he took them. He was the one who wandered into scenarios still foggy with death’s residue. Like the ominous, faked stains on the recreation of the hitchhiker’s Polaroids, they tell just as much of a story as an object.

That story is usually horrific.

Sometimes the Polaroid in such scenarios can actually provide a clarifying quality to the debris and chaos of a crime scene, especially one of murder. Take this example from P.D. James’ Shroud for a Nightingale (1971), one of her celebrated detective novels following the precise and intrepid Adam Dalgleish: ‘Twice more the distorted image leapt at him and lay petrified in the air as the photographer took two pictures with the Polaroid Land camera to give Dalgliesh, the immediate prints for which he always asked.’

There’s a great deal to explore in this one fragment of James’ slow-burn tale of murder in a nurse’s teaching ward. Firstly, James describes beautifully the essential essence of what taking a Polaroid actually feels like: the freezing of time in mid-air, peeling away reality to form a likeness. They earnestly jump out of the moment, even a sordid one.

The second aspect is more interesting, namely the question of why Dalgleish insisted on keeping the immediate prints, something he apparently always did. Dalgliesh looks at these prints of the dead student’s room while he’s actually still in there. What does the Polaroid reveal about a murder scene that standing in said room does not?

Similarly to Phil from Alice in the Cities, there’s a practical element to Dalgleish’s gazing. They foreshadow the constant criticism aimed at the screen-addicted youth of today who seem to live with their eyes glued to pixelated fantasies, even when the real world is all around them. Perhaps it removes the detective from the emotional charge of the death, allowing for calmer analysis, but this contradicts my thoughts on Polaroids: they really bring you closer to reality.

A Polaroid can make even the most banal of rooms and spaces look like a crime scene. They do not require the gangland scrawl of Hopper’s photos or the underworld grime of its subject to imply a death. A banal space captured in a Polaroid automatically raises a quiet suspicion, asking the question ‘Why was this taken?’

Or perhaps even more specifically: ‘Who died here?’

Polaroids go hand-in-hand generally with crime, and not just crime featuring death and murder. It’s still only recently thanks to digital technology that there is relative privacy in the creation of pornographic images, for example. Instant photography was a cheap and easy way to make them, industrially, personally or criminally, unless you had a developing studio of some form. Under-the-counter markets flourished briefly.

Our idea of blackmail, too, is so dominated by older crime novels (and older photographic forms) that it’s easy to forget how much Polaroids cornered that particular criminal narrative in the Post-War age. Images of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1939), with a hidden camera in the statue capturing Carmen Rutledge in a compromised position in some smoky, out-of-town pad come to mind (and rendered even more respectable in Howard Hawks’ film version). But it’s all so elaborate compared to the post-Polaroid age.

In Jackie Collins’ Hollywood Kids (1994), on the other hand, Polaroids are the more fitting tool of blackmail. Naked bodies writhing under their white light become a sleazy currency. When trying to get to the bottom of a particular Polaroid image of a compromised individual one character quips ‘Ooh baby, you could get arrested for carrying this around.’ Even Ian Rankin’s John Rebus interrogates a peeping tom suspect who likes ‘Amateurs.’ ‘That’s your style. All those blurry Polaroid shots, heads cut off. That’s what you like, eh, John?’ The cold autopsy-esque atmosphere turns on the more derranged of crime literature’s suspects.

There’s some connection in all of this to where the darkness of Polaroids ultimately tends: to the realm of maniacs and murder. The personal, private world of image-making opened up a Pandora’s Box of horror.

The Polaroid camera attains a distinctly weapon-like aura, even when not wielded for blackmail purposes. The murderer in Jean-Patrick Manchette’s thriller Fatale (1977) carries a Polaroid camera with her as if it’s an essential weapon in her arsenal, housed in her handbag alongside ‘doubles of every key to [her] lockers, and six 12-gauge shotgun cartridges.’

Old tales of peoples of the world fearing their soul to be stolen by photographic recreation comes to mind, like holding a bloodied dagger out in front of the person just stabbed. As an idea, this has been realised quite literally in Lars Kevberg’s schlocky 2019 horror film, Polaroid. In a distinctly digital world, the analogue immediacy of the Polaroid combined with being a physical object, is threatening. In the film, it spells doom to those who have their photographs taken, borrowing the idea from Richard Donner’s The Omen (1977); though in that film the discovery of ominous shadows hinting at future demise is tenser due to the omens being slowed by 35mm development. Polaroid is a weak film, not bothering with real Polaroids, opting instead for questionable digital recreations, but the essence of its idea remains.

Polaroids render faces as corpses.

The smiling faces of people enjoying themselves attain a morbid, sickly quality. When we hold a random Polaroid of someone, it’s increasingly likely as the years go by that it’s not only showing someone dead but was taken and held by someone dead too. The writer Gordon Burn understood this. His characterisation of the singer Alma Cogan suggested as much in his 1991 novel Alma Cogan. ‘If I think of the children as being – how shall I put this? – dead, of having retreated from, rather than moved forward into their lives, that is partly the effect of the Polaroids,’ he writes knowingly, ‘which have become sun-bleached (the light here most of the time is hallucinogenic and bright), giving the young flesh a green, loose-on-the-bone, sickeningly disinterred look.’

The ageing process renders these photos unique in the way that bodies are unique. Time passing distorts and ages the people within them. The grain becomes bleached like bones in sunlight, the skin greening and peeling under the relentless white flash of time.

We all have some basic understanding of the deathliness of Polaroids. Characters in M. John Harrison’s novel Climbers (1989), for example, show how unspeakably unnerving they can be when death takes precedence. The narrator of the book is always taking Polaroids. ‘The picture deteriorated in some way – perhaps because of the cold – soon after it was taken, chemical changes giving the light a dead green cast,’ he writes. Even the brightest colours have a deathly pallor.

In one scene in the book, the sister of a climber who has died from a fall is shown a Polaroid by the book’s narrator. ‘It was an eerie looking shot,’ the narrator suggests. He hands it over to her but she doesn’t recognise the man in the photo. As Harrison writes, ‘she pushed the Polaroid roughly back into my hand, incapable of comprehending how or where it had been taken; or why. For a moment, I couldn’t understand either …’

It cannot be looked at, this Polaroid. It is more deathly than a normal photo.

It was there, in that lived moment.

The moment and its subject have since decayed.

Her beloved brother has been outlived by a rubbish photograph.

…

The presence of a Polaroid in these darker contexts is sometimes unbearable. They transport the viewer so directly into the scenario that they seem cursed or tainted. Handling them becomes almost unimaginable.

The quality of a Polaroid is owned by the moment it was taken in, and the feeling is especially heightened when that present was particularly horrific. This sensation of being taken to unimaginable places came to a head when, by chance, I came across Polaroids taken by the notorious serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. But first, a minor diversion.

Serial killers have had a noted relationship with Polaroids, real and fictional. We know that Clarice (Jodie Foster) has finally tracked down the house of the serial killer Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991), not because of anything specifically morbid (at least at first as his true habits are kept deep in the basement) but because she finds Polaroids of a woman he has already murdered. Salacious images set off alarm bells for the FBI agent and rightly so. The Polaroids also suggest, as Demme mentions in a commentary track to the film, that the killer is confused about his own being, clearly seen with strippers but believing himself to be suffering from gender dysphoria. They have a disturbing, medicinal quality, almost as if they are morbid objects of scientific study.

British murderer Fred West was also a keen Polaroid taker. According to Gordon Burn in his book Happy Like Murderers, his Polaroids were a grimy erotic expression. ‘Polaroid cameras were the perfect kind of camera for the kind of pictures Fred West liked taking’, Burn argued. ‘They were fast –virtually instant; and, more important, the film didn’t need to be taken for processing by somebody else.’ Along with showing people the ‘rusty-looking tube and rods’ that he used for abortions, West also proudly showed off a growing collection of black-and-white Polaroids of vaginas, taken on his stolen Polaroid camera. It was often a gateway into an initial sexual relationship before quizzing women as to whether he could convince them to join in with his and Rose’s horrific pastimes.

In an even more unnerving scenario recounted in Burns’ book, West shows a pair of women a room where a camera is set-up at the edge of a bed next to a trunk filled with photos. It’s only when the two women look to the walls that the penny drops. Plastered all over the wallpaper is a layer of Polaroid images ‘of naked men and women in various poses. She could see from the satin-finish wallpaper in the background that the photographs had been taken in that room.’ It must have felt like walking around inside his skull.

The Polaroids reflect the room back upon itself, the homemade pornography ironically showing how a Polaroid’s presence works. Like Clarice hunting Buffalo Bill, Polaroids were an obvious clue as to potential danger. The pair quickly and thankfully fled from West’s room.

Neither West’s nor Buffalo Bill’s Polaroids reach the sheer horror of Dahmer’s, however. Verging on becoming a piece of urban folklore and known sometimes as the Milwaukee Cannibal, Dahmer is known to have murdered 17 young men between 1978 and 1991. His infamy comes not simply from the sheer number he killed but the practices he indulged in surrounding his victims after death, from storing their body parts to necrophilia and cannibalism.

Having initially searched generally for crime scene photography, his photos came up first in the search engine and they were undeniably the most disturbing Polaroids I’ve seen. They realise fully that same, terrifying aesthetic I had first seen in Hooper’s film. I had no inkling that such an absurdly overblown piece of horror fiction could find itself paling in comparison to our own murderous reality.

In the few I could stomach to look at, they begin as a sort of grungy rendition of Robert Mapplethorpe’s erotic photography. A naked man, who looks disturbingly like the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, is bound with rope and contortioned into suggestive poses while lying in what seems a blandly normal flat. The space is unusually empty, suspiciously so even. It’s only when seeing the final photo in the set that there is finally recognition that this isn’t mere pornography or erotica as the man’s head, hands and penis are severed and displayed neatly like ornaments.

Mere scans of these Polaroids are powerful enough, in fact too powerful to consider sharing here. But then, I imagined what holding one of these objects would feel like. It would be akin to holding a knife or some other weapon used to kill someone. The Polaroid camera and images were part of the crime in this case, a disturbingly creative aspect to it even. The presence of the Polaroid in these moments, infamous in the annals of American crime history, renders them virtually cursed. It’s impossible to imagine touching them.

I think it would even be impossible to be in the company of them for any length of time, more so than any of Weegee’s grisly images which, while effective, seem distanced in comparison. These Polaroids are from that hopeless, depraved world, rather than simply a reflection of it, from that last unbearable and humiliating moment of someone’s life, captured for prosperity by a dangerously broken mind.

These aren’t props from a horror film. These are real.

The feeling they give rise to finds a fitting metaphor in the Polaroid work of an artist called James Nitsch. Though rarely celebrated, the recent Polaroid Project shone a light on his work. His images broke the mould by having their subject breaking through the photographs, especially when that subject was a simple object.

In 1976, Nitsch created a fantastic image of a razor blade, the blade outside of the Polaroid ageing with time but remaining in its original vibrant form within the frame. The point in citing Nitsch’s picture is two-fold: it captures the feeling, quite literally, of when a subject, even a dull one, seems so fresh as to escape the frame. But the razor blade is especially effective as a subject as it insinuates violence.

Like Dahmer’s Polaroids, the subject remains fresh, stored in vinegar, pickling. The disturbance is because these are things that desperately want to be forgotten, especially in the public consciousness of America. But Dahmer’s bodies, alive or dead, seem to spill out of his Polaroids; their subject so beyond the pale as to linger, like Nitsch’s blade poking out of the frame, long after viewing.

A Polaroid brings out the deathliness in a situation. Diane Arbus famously described photography as like a stain and I like this description in regards to these darker Polaroids. Photographs ‘are the proof that something was there and no longer is… And the stillness is boggling. You can turn away but when you come back they’ll still be there looking at you.’ This quote came to mind after having seen those crime scene images, people staring back with the eyes of the dead. They truly were, to my mind, the closest photography had come to being such a stain, morally and aesthetically.

Dahmer’s Polaroids in particular are the ultimate human stain. ‘We leave a stain,’ wrote Phillip Roth in his novel, The Human Stain (2000), ‘we leave a trail, we leave our imprint. Impurity, cruelty, abuse, error, excrement, semen – there’s no other way to be here.’

If humanity’s stain was an image, the most effective form to document it would be a Polaroid.

…

If a moment of capture was not as charged as in these terrifying instances of psychopathic photography, I believe the Polaroid still has the power to summon morbid qualities; of death and violence. Sometimes it seems to do this when the subject is inane, and I wanted to find some half-way point to experiment with this idea. It was clear that a location was needed with some sort connection to death for such an experiment, and yet one which would on the surface seem banal. Perhaps like those who propose Stone Tape Theory – where a place retains events that have happened there, in a supernatural as well as physical sense – I wanted to see if a Polaroid could, so to speak, replay the tape.

I wanted it to be like the park from Blowup, except that, unlike Stephen, I would be certain of a murder having taken place, even if I was not going to photograph a corpse. My theory was that, taking into account and considering the auto-suggestion of knowing a place to be touched by death and murder, a Polaroid would still likely exude morbid, unnerving qualities.

Initially leaning towards a location where Jack the Ripper had taken the life of one of his victims in East London, it became clear that development and more than a century of changes since his killing spree in 1888 would have made the work of the Polaroid almost impossible; even if the atmosphere held within is still tangibly grim. The locations that did exist were also reified by the veritable cottage industry surrounding the murders, several surviving sites where the killer brutally murdered his victims now possessing plaques commemorating the tragedy and haunted by guided tours.

I visited the locations from the “five” canonical ripper murders one Boxing Day (in a period still haunted by the emptying effects of the Covid-19 lockdowns) and found the Polaroids looking more like the sort of photo taken by the suits and high-vis wearing developers largely responsible for the Ballardification of the East End. The site of Mary Ann Nicholas’ murder, for example, is now entirely subsumed by developments for the Crossrail project. No amount of Polaroid photos will make Crossrail interesting, eerie or morbid.

The rest of the locations seemed equally dull. I felt, on the walk, that this was down to the sheer changes East London has seen rather than proof that Polaroids can only take you so far. At times, the clash of architecture gave a hint of the old, dark London trying to emerge. It wasn’t an outright failure, though I felt the spirits stayed subdued in these photos.

Those deaths passed comfortably (or perhaps uncomfortably) into legend and was a subject too surrounded, analysed and known for my purposes. The deaths created an endless ghoulish industry, half conspiracy theory, half misplaced armchair activism, always a hypocritical bestseller. It was during initial research for such locations that I came across the actions of Jack’s more modern namesake, Jack the Stripper, and it was here where I found my ideal subject matter to test the Polaroid.

Sometimes known as the Hammersmith Nude Murders, the reign of Jack the Stripper over swinging London in the 1960s was short but terrifying. Over the course of several months, this still anonymous figure murdered six young women. Several nightmarish factors captured the imagination of the general public, and he still holds a grip of interest on a number of writers, in particular David Seabrook who explored the killings in his book, Jack of Jumps (2006)

The murderer, whoever he was, strangled his victims with stockings and also took several teeth for keepsakes. Most importantly, he got away with it; spawning a veritable but low-key range of books and cranks suggesting various possible identities, from a famous but troubled film star boxer, to an unidentified police detective (and, most recently, an infamous Welsh child murderer).

Interest in this morbid subject plays similarly to the likely interest in Jack the Ripper in the same period. Roughly the same number of years has passed between now and then as between the 1960s and Jack the Ripper’s killing spree. The shabby, ramshackle character of London then is deeply interesting and incredibly alien to me, especially as the area of West London, where the killings took place, has evolved from down-and-out industrial waste ground filled with villains and filming locations from The Sweeney, to an upmarket hideout of middle-class Zone 3 suburbia. Just as the East End of the original Ripper locations has changed, those of Jack the Stripper have too.

Or so I thought.

Being interested in this seedier side of London, manifesting in a curiosity about everything from the Kray Twins to the novels of Derek Raymond, the killings had an undeniable cultural impact that I found fascinating. Arthur La Bern used the killings as a model for his 1966 novel, Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square, later adapted for the screen in 1972 by Alfred Hitchcock under the title of Frenzy, while Cathi Unsworth novelised the killings in Bad Penny Blues (2009). Even pulp horror films such as Robert Hartford-Davis’ The Fiend (1972) directly lifted the killings (and even the locations) for pulp horror effect, and the likelihood is that virtually every reference in British film and television to “sex murder” at the time was likely an echo of the Hammersmith Nude Murders.

Today, they possess a continuity to a very particular nightmarish London, one found equally in the films of the early 1960s, the novels of Muriel Spark and Simon Raven, as well as the plays of Harold Pinter. It’s a London of quiet despair, villains and sleazy happenings yet is equally the same London that Ringo Starr briefly wanders through in A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and the city that Leon Kossof, Christopher Chamberlain and Frank Auerbach took pains to capture in oil paintings. It’s a London of cobbles, alleyways and stray cats; the stench of lacquer on beehives, backstreet aborton clinics, and Richardson Brothers crucifying men to the floors of South London warehouses for unpaid gambling debts.

I wanted to visit one of the locations used by this murderer. It wasn’t difficult to research the locations where the bodies were found as they were broadcast like an old crime drama with big white X’s dramatically marking each spot for a film made when the police reached a dead end and they put out a public plea on the BBC. I had been intrigued by a series of press photos, too, in particular of the discovering of one body in an alleyway in Brentford. The images contain more drama than most television serials today, filled with weeds growing through the pavement, disintegrating mesh fences, run-down garages filled with secrets and detectives in coats as long as their faces.

You can see two Londons in the photograph: the older, fading London in the houses with the busy chimneystacks (still spitting out thick smoke), and the modern London sprouting further towards the river in shadowy high-rise blocks. It’s like a still from an episode of Special Branch or New Scotland Yard but more visceral and more terrible than any teatime procedural. It’s an image of deep melancholy, the true darkness of a decade so often characterised as being colourful. It’s the Eleanor Rigby reality of an era desperately seen with Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds optimism. This was where I wanted to photograph, simply to see what the Polaroid would bring out, if anything at all.

Polaroids can give voice to the history of a single place, good and bad. I wandered to this same location on a stiflingly hot day, taking the tube way out west, hoping to catch a glimpse of this ghostly history. In many ways, the streets felt like a time-warp. The first building directly outside the tube station was a 1960s-built modern block, so pristine that it could have been built this year. It’s the sort of suburban area that still has the same residents of decades past, many doors and house frontages exactly as they were; frosted glass and all. Behind the rows of streets, a labyrinth of almost forgotten alleyways winds, buzzing with insects on the ragwort and buddleia outside empty garages.

I found the alley in question, nestled between the beginning of a beautiful suburban road and a playing field. A few of the tin roofs had been replaced by bigger, more formidable work spaces for the neighbouring houses but not much else seemed to have changed. It reminded of a promotional video I’d watched in awe for The Kinks singing You Really Got Me in a make-shift alley; the band sat on crates and bins in between fake brick walls and ironwork with a few stray cats lounging about.

I snapped my Polaroid without thinking too much about what the location meant, quietly worried that it would show nothing of interest. The area seemed so banal that I actually thought twice about taking it, such was the potential waste of going there and using an expensive image on what seemed to be nothing. But looking at the Polaroid on the tube back after it had spent time developing between the pages of an equally cheery volume of Sylvia Plath’s poetry, it became clear that it had been a worthwhile trip.

The Polaroid didn’t seem to show the location as visited on my day but one far in the past, closer to the time of the murder certainly (though it’s worth noting that the killer likely murdered the victim somewhere else and merely deposited the body there). More than this, I felt that the deathliness of the location was keener, like one of Dennis Hopper’s Polaroids of gangland territory or evidence used by Inspector Dalgliesh taken by a lowly forensic officer. Like Stephen’s photos in Blowup, it begged for a body to be glimpsed, slumped against the wooden fences or intertwined with the weeds. I zoomed in later after it scanning it just to make sure.

Of course, there was nothing.

Its green haze brought the history closer to reality and out of the clutches of urban legend. This was a tragic place, a place where virulent violence towards women was shrugged off by the media once they’d wrung every inch of salacious copy out of it.

“Giant hunt for sex maniac killer!”

“Prostitutes called easy prey for serial killers”

“Yard warn women”

“Big hunt for killer of Nude No 6”

The alleyway looked like a crime scene under the Polaroid’s flash. It was an utterly unavoidable deducation.

The Polaroid was evidence.

Roland Barthes wrote that all young photographers grapple with this feeing to a degree. ‘All those young photographers who are at work in the world,’ he wrote in Camera Lucida, ‘determined upon the capture of actuality, do not know that they are agents of Death.’ I felt like I had become one of these agents, summoning crimes from the past for my own morbid curiosity. I didn’t want to consider any of this anymore.

When finally home and scanning the image, my flatmate arrived from work to find me pouring over the photo and several other more innocuous Polaroids I’d taken that day for work. She picked the photo of the alleyway out of the pile immediately and looked at it for a short time.

“What happened there then?” she asked.

2 thoughts on “Presence, or Polaroid Ghosts (Part 15)”