Easy Riders, Cops and Maniacs

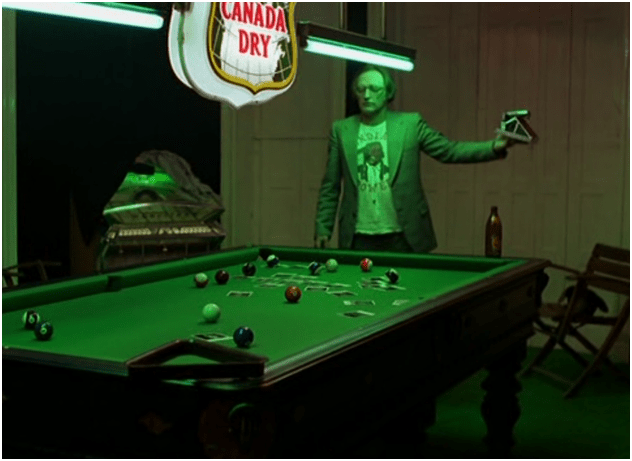

A man is stood in a pool hall. He’s surveying the green baize landscape as he drinks. Should he bother with the game anymore? The light has a medicinal quality, emanating with an annoying buzz from a long halogen strip above the table, proudly advertising Canada Dry ginger beer. It could be a lonely portrait by Walker Evans or William Eggleston, perhaps even an Edward Hopper painting.

The table is littered with pool balls but also Polaroid photos, discarded like passing thoughts.

This man is alone.

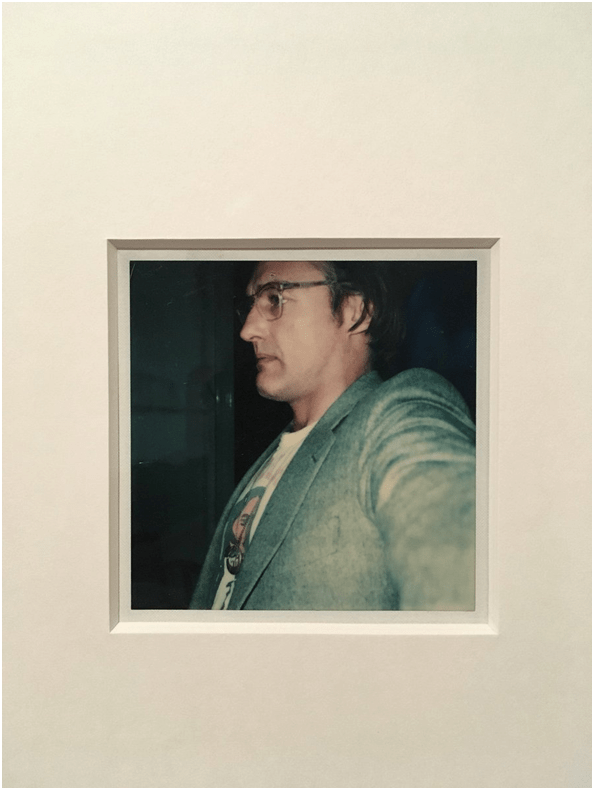

His hand reaches for a bottle and he takes a deep swig. I doubt it’s ginger beer he’s gulping down. He loads a Polaroid Land Camera, sat next to him on the green cloth, with another box of stock. Holding it away from his body while looking straight ahead, he refuses the camera’s gaze; almost as if he’s taking his own criminal profile for police records or documenting a crime scene in which his body is somehow involved.

The camera snaps and spits out his likeness. He doesn’t even look at it, merely throwing it onto the table among the shining pool balls. He begins to take more, gradually lowering himself as if to sleep, firing off Polaroids that document his descent. They fall onto him in a ritualistic manner. He’s trying to find himself but the photos fail to help. If anything, they add to his cynicism, capturing the white emptiness of his soul as he sinks away from reality, just for a moment; haunted only by the sound of the camera as it continues to empty itself of images.

The man in question is the actor Dennis Hopper, and the scenario taking place is from Wim Wenders’ 1977 film, The American Friend. The narrative is not of primary importance here, for the scene feels self-contained. Hopper’s character, the infamous Tom Ripley from Patricia Highsmith’s novels, is lost. No matter how many Polaroid selfies he takes, he won’t find what he’s looking for. His existence cannot be confirmed by them.

Ripley seems to be seeking confirmation of his own identity, his clearly dubious morals having hollowed him out over the years. He couldn’t have chosen a worse way to re-establish his sense of self. Like my deathly Polaroid – taken in pretty much the same fashion, even stretching into similar positions in order to find how best to capture my face on that awful afternoon – it reveals precisely what we don’t want to see.

It emphasises the deathly, the morbid, the dying and the dead.

Even the most alive of people sometimes look dead in Polaroid photos. Several years down the line, I imagine my Polaroid would have simply displayed my skull, the skin rendered translucent by the flash like an x-ray. Ripley’s Polaroids came out in a similar vein.

In light of Wenders’ work, it’s worth noting that this was the first film by the director to feature any sort of death onscreen. It’s a long way from the Polaroids of Alice in the Cities. But even with its occasional scenes of violence and murder, the film fails to attain the same morbid qualities as the scene in which Ripley takes Polaroid selfies in the bar. Hopper may as well be a ghost trying to return to Earth.

There’s something violent about the scene, too, though no specific violence occurs. He’s prodding and kicking his own body, trying to find life within some fleshy crevice. It’s a creative act of self harm. The scene confirms one thing in particular for me: that things – whether people, objects or places – attain the qualities of the dead when housed within the aesthetic of a Polaroid.

When visiting the exhibition of Wenders’ Polaroids in Soho a few years back, it wasn’t the Polaroids themselves that the viewer first became aware of when approaching the exhibition. On the echoing, thin stairwell of The Photographer’s Gallery, the exhibition actually drifted out of its main room. This was thanks to a video clip of the scene in question playing over and over on a loop, loud and continuous like torture. My thoughts went out to the volunteers who sat invigilating the space, tormented by the endless sound of Ripley’s futile soul-searching.

Played in endless repetition, even the sound of the Polaroid had something morbid about it, the mechanical repetition insinuating something painful. It felt akin to hearing Ripley self-flagellate with a cat-of-nine-tails. The blurring between the film and reality came full circle, however, thanks to one of Ripley’s Polaroids being housed next to the television screen replaying the scenario. The result was unsurprising.

Even compared to Robby Müller’s distinctly melancholy cinematography, so distinct that Müller and Wenders had to fight the developers in order to stop them trying to “fix” their images, Hopper in the Polaroid looks like someone about to face death. It’s a visual suicide note, not dissimilar to my own Polaroid, except I was looking directly into camera.

That white light is of the same quality found in a mortuary, shining off marble flesh with blood no longer rumbling beneath. Of course, photography on some level always expresses this relationship, for the likelihood is that the image, whether rendered a physical photograph or just sat on a hard-drive somewhere, will outlive the person it captures. Teju Cole understood that this often provided photography with its memorial qualities. ‘But when the photograph outlives the body’, he suggested, ‘when people die, scenes change, trees grow or are chopped down – it becomes a memorial.’

The Polaroid allows this process of memorialisation to begin before the person potentially photographed has actually left, starting the instant it exists; after those few moments of development. It becomes a weird future rendition of the past, where the impression of how our deathly bodies may look, even if smiling or happy, becomes apparent.

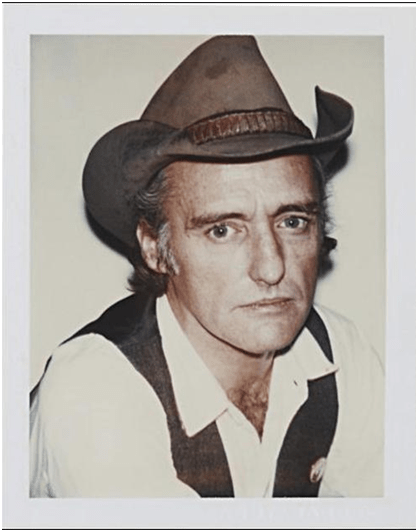

Hopper himself had a longstanding relationship with Polaroids, an actor who was drawn in front of and behind their bright stare. Alongside his own selfies in The American Friend, Wenders took a number of Polaroids of the actor, all capturing that same lonely distance.

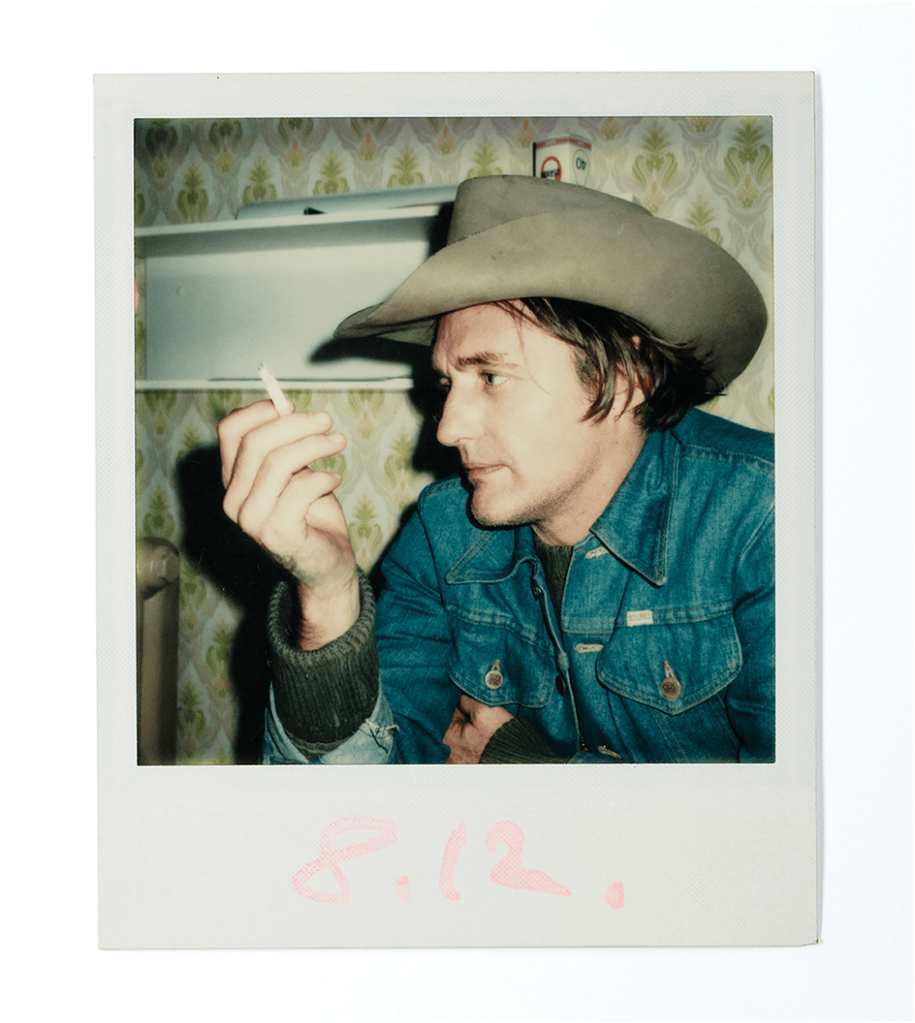

In one photo, he is dressed in an outfit more fitting for a cowboy. Along with the typical Stetson hat, he’s wrapped in denim, smoking in a down-and-out room like something out of a Sam Shepherd play. He looks taken out of time, a man from the past brought to a future where he’s just stepped over his own grave. It’s just that the grave happened to be a Polaroid; his eyes forced to witness his own memorialising in the present. As a man who was surrounded by death and calamity, as well as possessing one of the severest addiction problems Hollywood ever witnessed, it’s not hard to understand why this aesthetic chimed with the actor.

Hopper was clearly someone who spent time considering his own mortality.

The image is littered with post-war décor. The intricate, garish designs lose their obvious vibrancy and become something more ironic. It’s a décor of the dead. For all its popularity and strangely alluring nostalgia, the aesthetic of earlier Polaroid stock, forever faked today, does nothing less than shine a true light on the bland reality of even the most romanticised of eras and places, especially when it comes to showbiz and Hollywood.

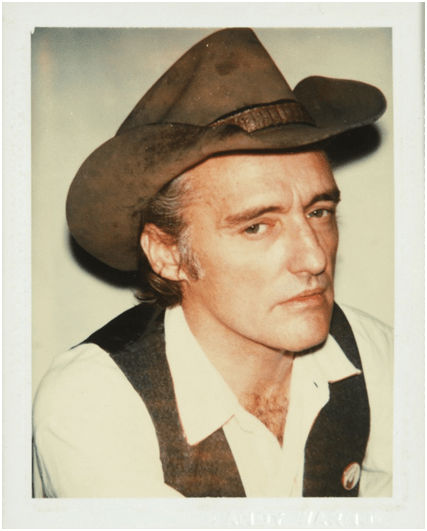

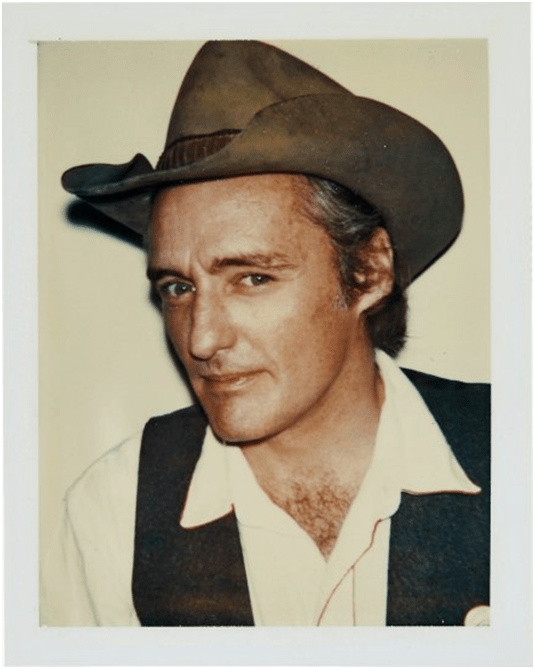

Hopper was also a regular subject of another noted Polaroid photographer: Andy Warhol. Warhol’s Polaroids are the most discussed by any artist, but his Polaroids of Hopper are especially worth investigating.

Taken a few years after Wenders’ photographs, Hopper has clearly aged, though it’s difficult to gauge just how much, simply due to the hedonism that his body had to cope with. It may have only been a couple of years. The actor is wearing similar clothing, again resembling a cowboy taken out of time, and the atmosphere is of a similar quality. He’s looking straight to camera this time. The room he’s in has the threatening white of a rehab clinic, and the photo is rendered blinding by his bright shirt that amplifies the flash. Even his skin seems translucent and thin. He looks like a demented angel lost in the Midwest.

Whenever Roland Barthes saw a photograph of himself, he said that he experienced a ‘micro-version of death,’ and it’s easy to understand why when looking at Polaroids of Dennis Hopper. Each one feels like evidence from a crime file. I wonder if Hopper’s character in The American Friend was thinking along similar lines, rendering the act of taking selfies appropriately suicidal. Or perhaps Hopper himself was feeling similarly lethargic at the time, explaining why he agreed to have so many taken of him. This was a man who really was becoming a spectre, destroying his body through drugs, and haunted from the very start of his career by the death of his friend James Dean.

Not all of Hopper’s portraits told such tales. Some of the series taken by Warhol show the actor laughing, suggesting that the moodiness may have just been a character expressed to the lens. It must be said, however, taking into account Warhol’s own relationship with celebrity and death, that Hopper looks like nothing less than laughing in the face of the reaper.

It’s difficult to gauge whether Hopper was projecting in any or all of these photographs. After all this was a man who famously hated recognition from his cinematic career, his face on screen as easily commercial as a Coco-Cola logo. ‘I don’t enjoy being recognised,’ he once said, ‘it’s unpleasant.’ Why so many Polaroids then? Is there a difference in likenesses here, something that means he doesn’t quite recognise his own image in the same way as when playing a character in a film?

Hopper died of severe prostate cancer in his Venice Beach home in 2010. Yet, if I’d seen these images before then, Hopper’s death would have been equally on my mind. Analogue photographs automatically imply the passing of the time: digital technology has rendered their everyday use historical and their specialist use (like mine) fetishistic. But Polaroids of this format especially feel like mementos of something lost, whether that something is a place or a person.

These Polaroids could have been handed out at Hopper’s funeral and no one would have thought it unusual. The gap on the bottom of the photo could easily have RIP scrawled upon it.

In his later years, having angered, annoyed and attacked most of the people in Hollywood that could have continued to give him regular work, in a strikingly similar guise to Walker Evans, Hopper picked up a Polaroid camera and began to wander. This wasn’t the first time the actor resorted to photography in order to make up for his streak of self-destruction.

In the 1960s, he’d taken to photography with great success. Followed by the notoriety of being difficult to work with (and not particularly unfounded), Hopper had become a successful photographer in a range of formats and publishing. His complex, fluctuating political leanings had favoured the radical in the 1960s, famously photographing several pivotal moments in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. Like Warhol, he also had a penchant for documenting the celebrities in his social circles, resulting in several published photo-books including 1712 North Crescent Heights (2001) and Dennis Hopper: Photographs 1961-1967 (2011). Hopper even photographed and designed the unusual cover for Ike and Tina Turner’s hit “River Deep – Mountain High”, showcasing a strange collage of musical information and cut-up, mountainous landscapes.

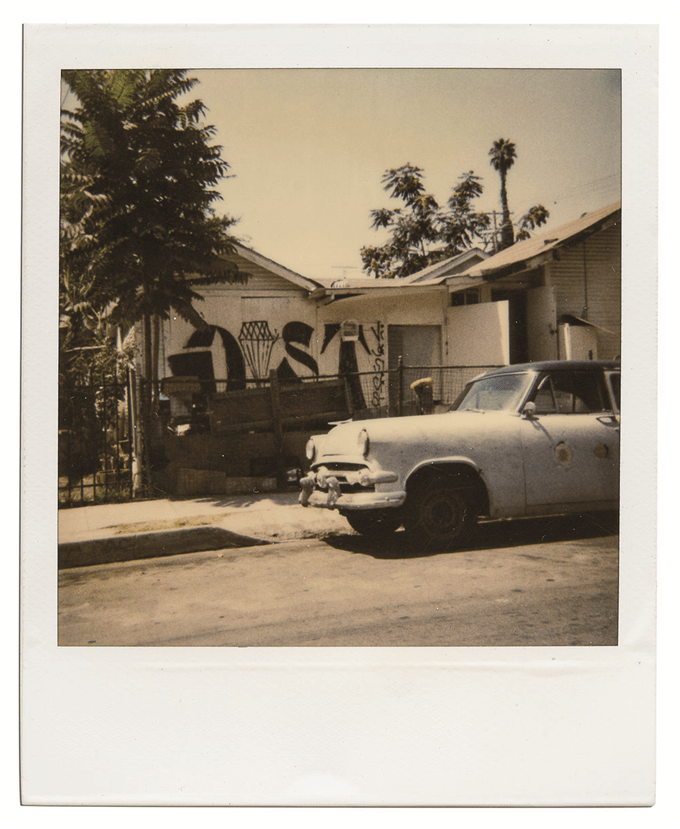

Yet Hopper’s most interesting photos were undoubtedly his Polaroids. In the late 1980s, Hopper picked up a Polaroid camera and decided he was going to document gangland graffiti that marked various territory and affiliations. It was simply research for a film. Yet, in doing so, Hopper actually ended up documenting Los Angeles and unconsciously captured it pre-gentrification.

The images are almost uniquely devoid of people, focussing on architecture and space, usually framed around a specific piece of graffiti or general evidence that the area is used by gangs. They seem appropriately taken out of time, sometimes looking much older than their 1987 reality. They are also quietly unnerving.

Either way, Hopper had an eye for what makes a good Polaroid, understanding what colours and busy textures worked best with his stock of choice. Even so, it’s unusual to find his images looking so deathly and strangely morbid.

Hopper famously suggested that ‘Art is everywhere, in every corner that you choose to frame and not just ignore and walk by.’ It’s a telling statement in regards to his Polaroids. These images acted as research for Hopper’s Colors (1988); his penultimate feature film as director following two cops as they attempt to deal with gangland violence in LA. The fact that the series of photographs was also eventually titled Colors, further attests to the connection between what he was capturing and the narrative he saw them being a part of.

These were places where seemingly innocuous shapes and squiggles quickly rendered with spray paint could spell potential violence, warnings and death. The hot atmosphere and colours are subtly subversive in their vibrant masking of this dangerous reality; a typical Hopper-esque ploy used in most of his directorial films, especially Easy Rider (1969) which sees a similar violence masked beneath equally colourful counter-culture imagery.

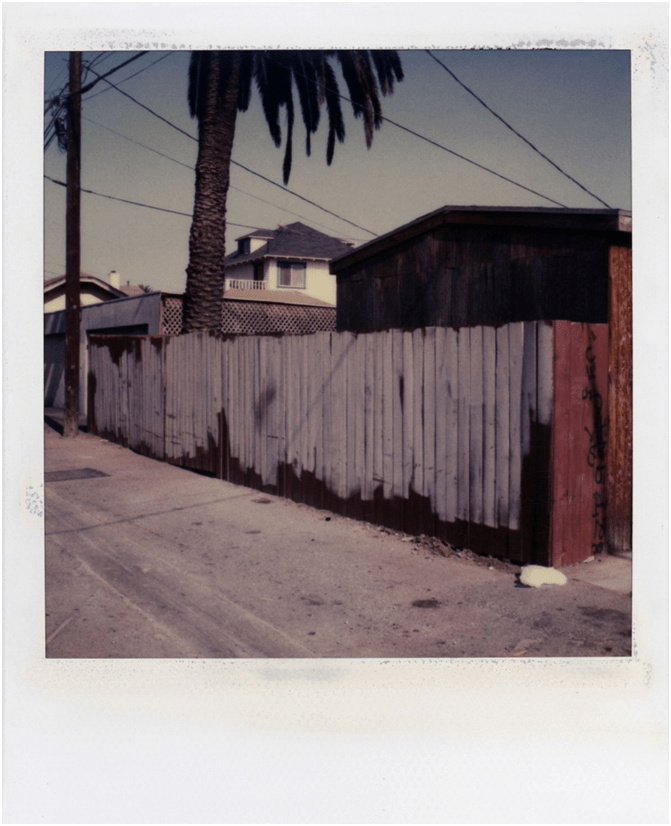

In the most unusual photos of series, even the graffiti is absent. One photo in particular stands out, if only for its suspiciously innocuous character. The Polaroid is of a back-alley between some ramshackle East Los Angeles housing. There’s no graffiti or sign of anything vaguely communal – it looks abandoned – which begs the question of what Hopper saw.

We as the viewer can see a few details; a piece of rubbish blowing in the warm air, a lonely palm tree drooping like a tired old man, a sky of buzzing wires and some fence posts painted half-heartedly in white. The latter point is especially interesting. Did someone paint over some graffiti? The paint doesn’t reach the floor of these wood panels so it certainly suggests that the primary goal was to cover something already on the wood rather than the wood itself. Did the area change hands violently between gangs? Was the neighbour annoyed at having their garden fence become a territorial marking and rebelled against it one bored weekend?

It’s not difficult to surmise that Hopper generally saw this place as one of violence and death. On first glance, it appears banal, perhaps even picturesque and not dissimilar to an Instagram photograph, but ultimately it’s the perfect setting for both real and fictional felonies. Jittery nervousness pervades, raised by unanswered questions surrounding what occurred in this place.

What did happen here in this forgotten Los Angeles backstreet? The act of photographing it alone aids the creation of this sensation.

Could it be one of the streets on the cops’ list to check out as in the film? Did it eventually make it into the film, the backdrop for a scene with Robert Duvall and Sean Penn to argue in? It takes little imagination to see the echoes of violence in these images once the context of the series is clear. If Hopper’s Polaroids truly resemble anything, it isn’t documentation of forgotten urban landscapes or sub-cultures, nor is it the simple results of a street photographer with an eye for places taken for granted.

It’s a crime scene.

One thought on “Presence, or Polaroid Ghosts (Part 14)”