The French philosopher René Descartes believed that his recollections were evidence he was not dreaming. He knew he was not asleep and merely creating the world in his mind’s eye because he was surrounded by things possessing a context that he was aware of personally.

‘But when I perceive things of which I clearly know both the place they come from and that in which they are, and the time at which they appear to me,’ he wrote in his catchy titled Discourse on Method, ‘and when, without any interruption, I can link the perception I have of them with the whole of the rest of my life, I am fully assured that it is not in sleep that I am perceiving them but while I am awake.’

I like to imagine the sort of objects that Descartes had in mind when making this argument, calling forth images of objects akin to a work in the Vanitas painting tradition; a still life containing various debris deliberately rendered meaningless by the presence of a skull and the inevitability of death that it insinuates. Everything tangible is eventually inconsequential due to death, life being merely a vanity of possessions.

If Polaroids had been around in Descartes’ era, I imagine they would have made for a perfect example in his discourse; faded shards of life that proved he was beyond his own dreaming. Perhaps a Polaroid could even sit comfortably among the bric-a-brac of a Vanitas painting from his era, though the inclusion of it would make the usual skull unnecessary.

All photography is on some level deathly.

Polaroids possess Descartian qualities because they capture more than just what is shown within their frame. They are proof that all of this is not some unsatisfactory dream because they fill in so many blanks outside of their image.

This cannot be a dream because when I look at my Polaroid of J.G. Ballard’s house, I recall other things besides the basics of the bricks and mortar shown in the image. I remember reading Kingdom Come on the train, plagued with the endless delays of South Western Rail. I remember the previous attempt to make that journey the week before, waiting around a stifling Wimbledon due to the cancellation of most trains out of Waterloo. I remember the cheap lunch I ate on the patch of land at the end of Ballard’s road, and the sign that reminded the rich residents of the area that riding their horses on the grass was prohibited. If I am dreaming up the world, then I am dreaming it in Ballard’s vision.

Polaroid photos animate our memories and are excellent at mapping journeys. This will always be more effective on a personal level but that is not to say the drama of such readings is impossible regarding photos that are not our own. On the contrary, this powerful character has been used in narrative art, drawing on themes of loneliness and disenfranchisement.

I was not the first to come upon this potential. Instead I am building on a semi-fictional device used in the films of Wim Wenders, a German film director who understood this power within Polaroids and used it to heighten the key characteristics of his meandering dramas.

Before his successful move into documentary cinema, Wenders’ films were initially dramatic travelogues; inverting the optimistic traditions of the American road movie and providing some much needed European pessimism to their journeys, whether they were across Germany, America or elsewhere. Many of his films are built on these lonely odysseys; Paris, Texas (1984), Kings of the Road (1976) and The Wrong Move (1975) being some of his most popular in this vein.

His characters are almost always on the road, but are perhaps unique in cinema in also having complex and detailed relationships to the Polaroid camera and its subsequent photos. The relationship is one that is also autobiographical, the director being a prolific Polaroid photographer himself. Even his regular cinematographer Robby Müller had a penchant for Polaroids. Both have had their photos published in lavish compendiums in recent years. The photographic work of both men is now considered as essential as any of the more celebrated Polaroid photographers, and rightly so.

Their work gets to the heart of how Polaroids travel and what they accrue in the hours between their adventures to nowhere. Wenders is keen to emphasise distance in his work so the Polaroid provides a fitting measure of certain points on the journeys of his characters, rather like pins between lines used to animate routes on maps in old Hollywood films.

Wenders’ films are cartographic, with their structure appearing initially linear as characters often try to travel from one place to another. Rarely do they follow a straight route, however, leading to the drama of chance meetings on highways filled with lost souls. Of course, the Polaroid is fitting for these narratives. It is a form drenched in loss; the loss of people, the loss of time, the loss of space.

Sometimes in Wenders’ films the Polaroid itself is actually the reason for the deviation. What better excuse to stop for a moment’s reflection than to snap a Polaroid of a road sign or beach? More often than not, these minor interludes are dictated by the forces of chance. The Polaroid turns these moments into something tangible.

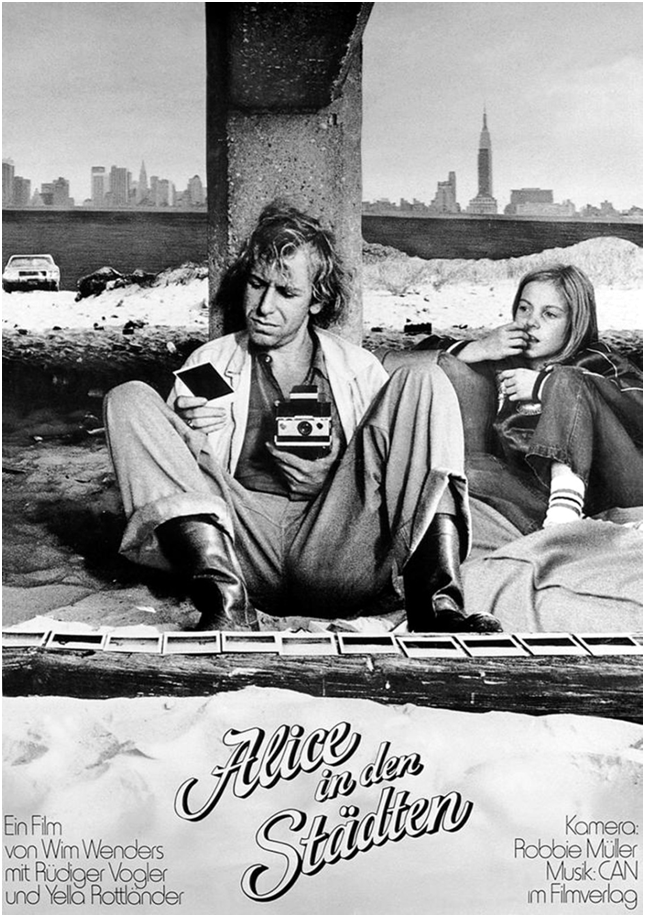

The first and most explicit use of a Polaroid camera for Wenders comes in his 1974 film Alice in the Cities. The journey of its narrative is caught in great detail by the lead character using Polaroids to map the haphazard route he is forced to go on via endless German roads and autobahns.

Following a chance meeting in America with Lisa (Lisa Kreuzer), journalist Philip (Rüdiger Vogler) ends up taking care of Lisa’s daughter Alice (Yella Rottländer) after being left with her at an airport. Travelling back to Germany, Philip decides to make the most of the journalistic opportunity in driving Alice back across the country to her grandmother’s. There is, however, one problem: Lisa did not say where that was, and Alice (who is only nine) cannot remember either.

At times, it seems that Alice wants to get lost with Philip, as if the prospect of the open road is more comforting than a static home with all of its problems. The film charts their journey on the road as the disillusioned Philip, who is suffering from a creative block, gradually comes to terms with his meaningless travel. It is a film that revels in meandering towards an ever-changing destination, sometimes infuriatingly so. But, most importantly, it is a film where the distance travelled is mapped, not simply by the endless roads driven along, but within the incessant Polaroids taken by Philip.

By the end of the film, it is the collection of Polaroids taken that mark out the various chapters and points on the journey as much as what the viewers themselves have seen. Most movies of this form – that of a haphazard journey rendered linear by the natural form of a film with a beginning, middle and end – have their narratives signposted by events.

If we were to rewatch a particular film of this general genre, we would know as a viewer roughly where we were in terms of the film’s journey by events that stood out (especially deaths). For Wenders, new characters entering and leaving often fulfil this role because technically very little else happens. And when there is only the road, the empty highway café or the derelict industrial landscape, then finally the Polaroid marks a point in the film rather like a cigarette stub suggesting the changing of reels.

Polaroids in Wenders’ cinema feel like the bending of a book’s page corners, yet are obviously far more significant as they capture that moment through detailed representation rather than simply a blank signifier of position.

The Polaroid camera is an essential part of the narrative, so much so that many of the posters advertising the film show Philip holding the device. There is a reason for this in that many scenarios in the film use the Polaroid to question the perception of the character and his detachment from reality. The poster in question sees the character sat under a boardwalk by a beach. In the scene it references, he takes out his camera and we see the landscape that he intends to photograph first. It is a fragment of beach furniture sticking out from the shoreline. He takes a photo and waits a little while for it to develop before staring at it.

His switch from looking at the real space to the space he has photographically captured is essentially his personality and predicament in a nutshell: why face the vastness of the real world when you can simply frame it in manageable reproductions and miniatures? The irony comes from the fact that we as the viewer only see such a landscape through a similarly analogue recreation; on Wenders’ 16mm black & white film stock.

It is only the predicament that he finds himself in with Alice that forces Philip, his camera and his photos to eventually travel. They accrue the whole of his journey, even the parts we do not see. They map the spaces in between each image as well as those within the white frame.

I recognise the look on Philip’s face in that poster. It is a strange stare, one that seems to ask ‘What is really real?’ Descartes would be satisfied. Philip is not.

The Polaroid destabilises reality around us as it reduces space to a flat image, all the while still witnessing what it has recreated in miniature. If you have ever watched the blue dot registered on a Google Map on your phone move as you walked in search of somewhere, you will have undoubtedly met with this feeling on some level before.

Perhaps it is the acknowledgment of your own physical presence, that realisation that our outer movements carry a weight outside of internal recognition, that creates the haunting friction. It is the closest an adult can come to reliving Jacques Lacan’s supposed ‘mirror moment’; that realisation of the self when first seen in a mirror as a child, the mind slowly aware of being and becoming.

The recreation of a Polaroid rubs up against reality and creates an uncanny effect because, like Philip, we switch ever more regularly between reality and mediation of reality. This is likely to be a less powerful feeling if younger and totally immersed in the digital world. Digital life turns the mediation of reality into an addiction of screens and blue light, normalising our slow transformation into apparitions. We know, too, that the space in a Polaroid will become historic, switching from mediation to sole survivor. The image will likely outlive us and, especially in the age of the Anthropocene, may even outlive the landscape itself, especially a coastal one like the location Philip captures.

There is another reason why the camera features so heavily in Alice in the Cities. The model in question was the soon-to-be celebrated Polaroid SX-70 Land camera, a new foldaway that was designed with travel very much in mind. Its easy set-up desperately asks its owner to wander, to store it with ease in a bag and leave the house. It was then just an early model so the whole film and what it produced (on screen and off) was one long experiment in the momentary capture of space, journey and memory on a new Polaroid device.

Wenders makes sure that the character is seen regularly using the camera, almost to the point of product placement; all the while genuinely capturing moments on screen that would be preserved in real life many years later. The process of taking the photographs becomes cathartic; partly for Philip to trick himself into believing there is any meaning to this distinctly random journey, partly to convince himself that this can act as journalistic work.

His editor at the film’s conclusion is sadly in stark disagreement with him as to the worth of his final box of Polaroids. Philip seems consigned to dismiss his photos, even if they do ultimately allow him to break through the block that was stopping him from working. Both characters are wrong as to the merit of those Polaroids. I know this because Wenders exhibited some of the surviving photos from the film alongside his own as part of his ‘Instant Light: Polaroid’ exhibition at The Photographer’s Gallery in Soho, 2019.

The photos blended together in the exhibition, the line between fiction and reality disappearing due to the character sharing much in common with the director’s compositional eye. They were, after all, on the same journey.

Later in the film, among the many scenes involving the camera, one in particular stands out. Alice wants to photograph Philip and takes the camera out of his bag. She quickly snaps a photo of him which we instantly see the result of, even without any time to develop. Such is the nature of filmic time that this does not really matter, though it feels like a final (fictional) nail in John Berger’s conceptual abyss between a photograph being taken and being seen.

‘I want to take a picture of you,’ Alice says, ‘so you can see what you look like.’ She does so and hands the photo to Philip who looks at it mournfully. He can see himself clearly, the space around him and everything else. The reflection of the shiny material also melds Alice’s face to his own, as if he is seeing a composition of the two; the situation is inescapable from the image as life continues on.

This is less of a point about space and more about action. Philip sees himself in a dead moment, the space reflecting back upon him just like my image of the tree in South London creating the effect of layering reality over reality.

In the Instant Light exhibition, this scene was actually mimicked, suggesting that it perhaps came from some improvised moment during the filming. A highlight came in two photographs taken during the filming of Alice in the Cities. One was taken by Wenders himself and the other by the young star playing Alice. First is the Polaroid of Wenders. It is an unusual photo in that it is taken from an unnaturally low angle, so low that Wenders has to crouch into the photograph. It feels, if nothing, like he is really there, looking in from the other side of a tiny window.

The explanation for this angle comes in the next photo as it shows Rottländer holding the previous Polaroid. She was clearly the first photographer, not only because the angle has now reversed to Wenders’ taller view looking down, but because she is actually holding the previous Polaroid. It is a witty, enjoyable play on the scene from the film. We get both sides of the view, a space marked by two distinctly different gazes, and all achieved without the slightest hint of pretension.

Gaston Bachelard wrote that space contains time. ‘That is what space is for,’ he confirmed with the authoritative voice of a school teacher. When looking at this pair of photos, I feel the relationship is somewhat reversed, as if these two singular fragments of time – time expressed through the presence unique to the Polaroid format – mark out the space of that moment.

This depth is surprising considering Wenders’ view of the Polaroid itself. ‘If ever I had wanted to really take a picture of something,’ he told The Guardian around the time of the exhibition, ‘I would not have done it with a Polaroid. I never thought of it as giving the real picture.’ In some ways I know what he means. The Polaroid is a memorial space rather than an image; it is beyond pure imagery because it has such an attached relationship to reality as a physical object. This is why 35mm is much more dominant: it is the photographic form because it is pure imagery. A Polaroid’s presence marks it as beyond an image.

When looking at Wenders’ Polaroids a number of things come to mind. Most play on the slippery reality between the production and the narratives of his films. In real life, he goes on pilgrimages much like his characters. His first Polaroids of America show the sort of excitement of someone finally visiting a dream realm; one concocted from years of having the vision of the country dictated by cinema. I get a similar feeling when seeing old Polaroids of holidaymakers in America from the same era, especially of Las Vegas whose desert extravagances and colours of excess were simply made to be photographed on Polaroid cameras.

Other images by Wenders show things such as behind-the-scenes production glimpses, the journeys in between filmmaking and visits to important sites such as the grave of Wenders’ great cinematic hero, Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu. His Polaroids bring another photographer to mind, perhaps because a vast amount of Wenders’ own photographs and films basked in the same imagery of heady Americana.

That photographer is Walker Evans.

Evans was mentioned earlier for his pronouncement of the Polaroid camera being akin to a toy. For the older photographer looking for an easier machine to use later in life, this was actually meant as a compliment. Yet, looking at the photos of Wenders, it is hard to disagree that a sense of play is not, on some level, a huge factor in taking Polaroids.

Evans’ own Polaroid photos, perhaps the most celebrated by a high-end artist outside of Andy Warhol’s work, attest to a greater complexity. His images explore travel and the melancholy fernweh of a wanderer searching for the unknown. It is likely that the highly saturated colours that define the Polaroid on the public consciousness – dripping with highway sweat and blinding blue skies – have largely come from widely shared images by Evans, taken on his favourite toy.

Evans first became notable in the Golden Age of photography, working for the Farm Security Administration during The Great Depression. Born in Missouri, Evans began his creative life by studying French literature. He soon moved to New York and worked as a clerk on Wall Street. It was not until the late 1920s that he moved into photographic work full time, appropriately publishing his photos alongside the work of poets. His work has always suggested the potential for footnotes and creative responses.

He was one of a number of photographers who pioneered street photography, almost always outside and rarely even supervising the development of his photos. Being indoors was not for him. This should give some indication as to why he eventually found much potential in the Polaroid: he could stay out for as long as he wanted, feel the subjects properly travelled and even see the results of his work there and then.

Evans worked for some of the biggest outlets in America, eventually writing for Time Magazine and teaching photography at Yale. The photographer died in 1975 at the age of 71, only four years after the first major retrospective of his work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1971. Before he died, his last two years were spent in the company of a Polaroid camera rather than his trusty Contax 35mm. The results are still truly extraordinary.

Polaroid provided Evans with an SX-70, the same camera from Alice in the Cities, and unlimited amounts of stock. It lead to a late career high in a portfolio already brimming with brilliance and important historical documentation. ‘I took it as a kind of challenge,’ Evans once suggested. ‘It was this gadget, and I decided I might be able to do something serious with it. So I got to work to try to prove that. I think I’ve done something with it.’

He was right. The photos he produced were startling, and still arguably the creative peak of the medium. It is impossible to see the images he captured without a wealth of other imagery coming to mind, due to how influential they were on the collective vision of twentieth-century America.

As with Evans’ 35mm work, his predominant subject is the country he wandered through, or perhaps more generally Americana. He adored signs, belying an interest and work in design. He spent a great deal of time photographing buildings, road markings and anything that suggested symbols or typography. The more dilapidated, the better.

Evans was a poet of Uncle Sam’s decay, as if the American Dream was disintegrating before his eyes into the dusty debris of empty roads, falling buildings and crass commercialism. With all of these subjects comes a sense of travel; Evans’ nowhere wandering readily apparent by the crumbling remains he found off the beaten track. He wandered far in order to find the degradation of his own land.

What I see in many of his images is journey. Even when other spatial qualities are clearly present in his work – the collapse of four walls, for example, as in his photograph Abandoned House (1973-74) – what is stronger is a sense of wandering. Though now held in the collection of the Met Museum, this particular image still feels a travelled object. I can imagine the image covered with dirt from the road before it was restored and placed in the collection.

The reading of the photograph is influenced by the subject; its space drifting into the characteristics of the object itself. I can feel the dry heat in this image, sandy ghosts kicked up off the road. I even feel the coming pangs of thirst as I look at it, my throat turning to dry wood.

Melancholy is a huge presence in his images, too, not simply in the absence within the spaces he captured but in his role in capturing them. He has the eye of a man at the end of his life, looking back and seeing things once known now reduced to ruin.

Sebastian Smee referred to Evans as a flâneur to account for his constant traversing of America’s forgotten highways. I am not sure if this is quite right, however. It assumes that a journeying photographer automatically possesses the qualities akin to the upper-class urban wanderer of nineteenth-century Paris, walking the arcades over a pleasant afternoon with no real meaning or purpose in sight except the pleasure of limestone daydreams and the aroma of coffee. This is not the feeling captured in any of Evans’ photos. He is too caught up in the moments and the working-class class lives he captured to fit in with the perambulatory distractions of a flâneur.

Evans has been compared to a number of artists, all for differing reasons. In the same article, Smee compares him to Édouard Manet as he ‘adored the chaos of the modern street and repeatedly fell in love with the enigmatic, inconsistent and incoherent.’ The anonymous writer tasked with describing his work in the collection of the Met Museum instead compares him to Henri Matisse, at least when using Polaroids. The ‘concise yet poetic vision of the world’ is one reason, another being that the Polaroid’s ‘instant prints were, for the infirm seventy-year-old photographer, what scissors and cut paper were for the aging Matisse.’ There is some degree of truth to both of these comparisons yet they rarely scratch the surface of the Polaroids themselves, pulling on broad gestures in Evans’ work. Certainly, Wenders’ films and photographs are a far better comparison due to both artists sharing a sense of travel as well as similar tools and subject matter.

Compare the two previous images. The first is by Evans, the latter (above) by Wenders. They could be stills from the same film. Both suggest the image has travelled a similar trajectory, as if on the same road trip; the first a brief stop for a coke and burger before following the tarmac to its very end in the second photograph; where the desert collides with the mountains. Any number of images could be put together and compared between the two photographers.

Wenders had the same appreciation for signs, cars and lonely street furniture as Evans because they both shared a love for drifting. The only real difference is that Wenders eventually dramatised it whereas Evans, if spending any time on other creative aspects, simply analysed it (albeit brilliantly) in writing.

I first came to Evans’ photos by sheer accident and ironically through other photographers trying to mimic his work. It was in a collection of photographs used on a cover of Don Delillo’s apt novel Americana (1971) when I first found pleasure in such similar images, though they were not by Evans. They were instead stock photos earnestly evoking his work – and to an extent, William Eggleston’s, another photographer of Americana who similarly turned to Polaroids – without the publisher having to pay the price to use an original. It was only through later coming across a book of Evans’ photographs that the connection clicked.

It is understandable why Evans’ style of imagery would fit a novel like Americana; a melancholy story of another lonely man, travelling to the mid-west in the 1970s to document it only to find the absence he was looking for was carried within him all along. His loss was pre-ordained before he took his first step. One line stands out: ‘Such is the prestige of the camera, it’s almost a religious authority.’ I see Evans’ photography within this description. It lifts mundane subjects to the state of something transcendent. As the Polaroid produces a physical object, this feeling for me is heightened, as if producing a holy relic devout in its worship to the deities of Coca-Cola and Ford Motors.

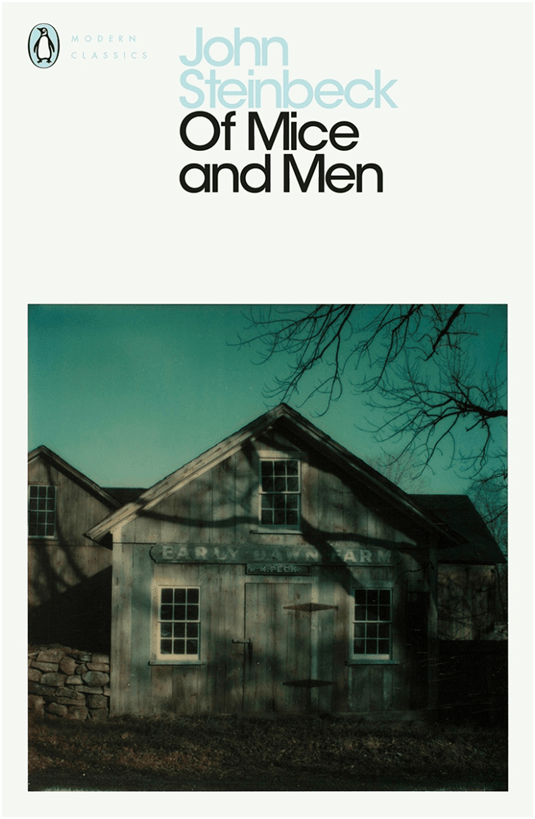

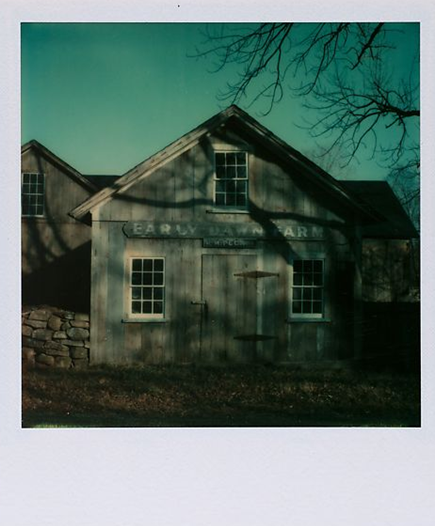

Aptly, Evans’ photography was eventually featured properly on book covers, especially for novels considered part of the American canon of the last century. In a series of modern reprints of John Steinbeck’s oeuvre by Penguin, every edition had a Polaroid by Evans on the cover. This choice alone highlights the interesting difference that the Polaroid presents within Evans’ work.

Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (1937) is now adorned with Evans’ R.M. Peck’s Earl Dawn Farm (taken in November 1973), its Polaroid character maintained (as across all of the editions in this series) by mimicking the original boarder of the photo in the white background of the book’s design. Steinbeck’s story tells of two displaced ranch labourers travelling between Californian farms, desperate for work during The Great Depression. Having searched through a range of editions, the only other photographs used to illustrate the novel’s cover in British publishing are stills from the Gary Sinsie film adaptation from 1992, and one single edition using Dorothea Lange’s equally appropriate photo Toward Los Angeles (taken the same year that Steinbeck published his novel), showing two men wandering the highway with their belongings in tow.

Evans was one of the key photographers of the Depression era, capturing many of its defining images. His 35mm photos are etched with strife and crippling hardship. He humanised the abstract financial loss with brilliance and heart-breaking clarity. If Steinbeck was the Depression author, which by most accounts he is, then Evans was at least one of a number of photographic equivalents. Yet, these Penguin editions opted for Evans’ Polaroids instead, photographs taken forty years after the publishing of many of these books and many more years after their period setting. Why then use something that, on a technical level at least, seems so obviously anachronistic?

The question is even starker considering the likely options they had of actual period photographs by the same photographer. Would the books have benefited from cover photos of the true period, of real people of the era rather than 1970s echoes of the same ruination? I think the answer as to why they still work lies in the essence of Evans’ journey housed within the Polaroids.

Journey is essential to Steinbeck’s work. The hardship of forced wandering through the remains of the American economy is the raison d’être of much of his writing. This same wandering is present in much greater clarity in the Polaroid images, not just in their saturated colours – as if they faded under the sun’s glare on the sweltering, endless road – but in the object itself. The photo genuinely did travel as much as the characters, much more than the 35mm photos, likely only travelling between galleries and magazine offices once developed in the New York studio where Evans was based. If any photographer accrues the same journeying in his images as a Steinbeckian creation then it is Evans in his final days of shooting, as the end of the reel came within view and the last few packets of stock were torn opened.

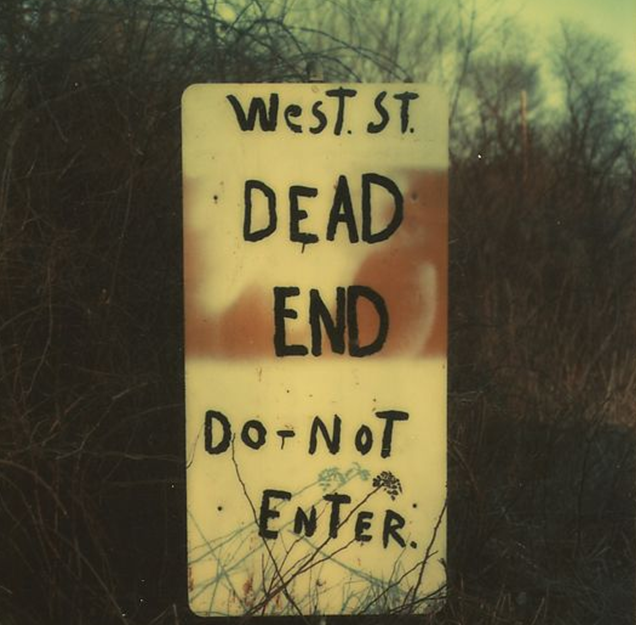

Still life is an ironic description for such a form, considering life is only really still when it is over and the bones are gathering dust. I think Evans understood this photographic contradiction, and looked to images that captured the necessary stasis required for all photography, all the while maintaining his expression of journey. In search of this, he found joy in the road signs and symbols that presented themselves on his travels.

Evans’ most powerful photos elicit the everyday world, highlighting the things we take for granted because we are too busy looking away from them once the information they barter in has been traded.

Coca-Cola is for sale there.

That house is falling down, stay away.

This road is a dead end, go back.

The latter is a reference to a series of images Evans took just before his death; focussing on a hand-painted road sign, West St. Dead End. It is one of the last photographs he took.

The Polaroid is one of Evans’ most stark, not least because the sign lacks the typically neat and tidy design that usually caught his eye. Even when buildings were collapsing in his photos, the signs were still impeccable, if a little faded. There is often the impression of a lost gentility, an engulfing emptiness. Here, it is a badly painted, impetuous warning, resulting in a number of photos zoning in on the detail of each segment, especially the ‘Dead End’ part. It feels so much like the end of the line for the photographer’s journey, quite literally; body and soul. The photos feel the most travelled of all his work, as if he started off one day in the late 1920s walking and driving, always with the aim of finding the end of the road that is finally suggested there on West Street in 1974.

In Judith Keller’s write-up of the Getty Museum Collection’s holdings of Evans’ work, she described this image as predicting ‘the garish negativism of American Punk subculture that it predates by nearly a decade.’ Aside from ignoring the incorrect time-line as to the founding punk (which the photo is really only a couple of years or so from), I think this reading removes the powerful presence acquired in Evans’ photographs.

Far from either garish or languishing in negativism, the photo to my eyes looks like the edge of the map that Evans had been sketching for some years. His own personal wandering, at least in this realm, was coming to an end; finding solace in an acceptance of death. He had driven and walked beyond the horizon under the big sky, to the ends of the country that was his beloved subject for fifty years.

I find acceptance in this photograph, along with the feeling that every photograph Evans’ ever took is in some way suggested – in tone, subject and atmosphere.

Beyond it lies lands out of reach.

‘The damn thing will do anything you point it at,’ Evans once bluntly suggested. ‘You have to know what you’re pointing it at, and why, even if it’s only instinctive.’ Journeying was the best way to acquire this knowledge, whether documenting asphalt jungles, crumbling economies or the destitute. But in these final images, Evans confirmed for me the stranger aspects of the Polaroid and how they map the world as we see it. He may have chosen it for ease of use when his physical prowess was deserting him, but the resulting photography was compounded by a machine that still pleaded with its user to wander. Combined with a photographer who needed little persuasion to get out on the road, it resulted in a photographic partnership since unmatched.

3 thoughts on “Presence, or Polaroid Ghosts (Part 5)”