Chance played a huge role in the writing of Robert Walser. I can picture his slow meanderings around towns and valleys, spotting something that fired his brief need to write before getting distracted by something else entirely. I can see him getting excited by the way sunlight reflects off a lake’s water, by the fustiness of a suited man coming out of a bank, by a woman’s lavish attire sending him into romantic daydreams; he was, surprisingly perhaps, a bit of a Lothario in that regard. Walser chanced upon small, beautiful details everyday and filmmaker and artist Tacita Dean did the same in her collage work inspired by him: Berlin and the Artist (2012).

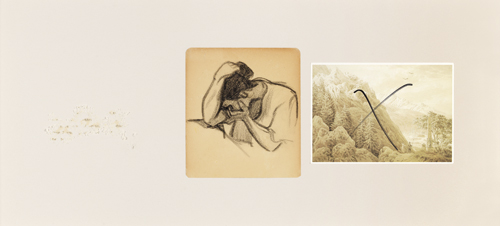

To coincide with an exhibition in New York of work inspired by the writer, Dean was commissioned for a piece and chose the subject of Walser’s time in Berlin as her particular angle, the title a nod to a story of by the author. Walser stayed with his brother Karl in this period, a noted illustrator whose work can be seen in a number of Walser compendiums, in particular on the covers of the latest New York Review of Books editions. Using found objects such as illustrations, photographs and postcards, Berlin and the Artist seeks to replicate such chance encounters while equally finding its own particular narratives in the lost and the found; in the meandering uselessness of creative daydreaming.

Dean set some parameters for these works. Rummaging through markets in Berlin, the objects she found and used were roughly from the same period that Walser was living and working in. She even came across new work by an illustrator called Martin Stekker whom she considers may have possibly met Walser through his brother’s creative circle of links and friends. In an interview for Frieze she told of the discovery.

‘Very strangely,’ she recalls, ‘we came upon hundreds of pencil drawings by an artist called Martin Stekker. It was a remarkable discovery: Berlin observations from a century ago… Well, they were beautiful and I knew I was working on this project, and Walser was already on my mind. I later researched Stekker to find only one reference to him on the Internet and discovered he was born in the same year as Walser. Just after that I bought another newly translated collection of Walser’s writing, Berlin Stories (2012) where I read Berlin and the Artist. Immediately I saw a connection between Stekker’s drawings and Walser’s stories, both observations of Berlin life from the same time.’

A Walserian coincidence if ever there was one. This layering of history and chance perfectly embodies the writer’s work.

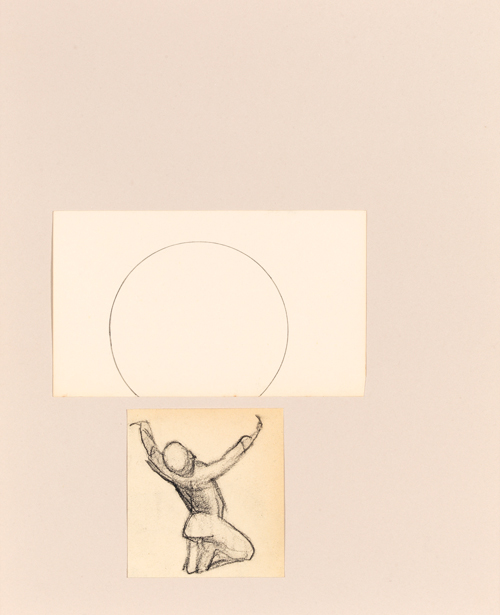

On an aesthetic level, such themes are expressed with equal effectiveness. In one of the collages, a sketch shows a man kneeling (perhaps even praying) while his arms complete a circle from another drawing. These objects are both self-contained and in communication with each other, aiding the effect of browsing through someone’s memories. In another of the collages, two separate photographs show a man writing at a desk. It is a different man in each photo and a different desk but the pair work together. Through difference there is likeness, rather like the cuts in a film; different angles and times creating one pleasing whole.

Even if such a form automatically contains some askance of meaning, it is not necessarily the point of the work. The objects are connected by a blank, aged looking card as their shared background, but separated into a number of different frames just so that the context of each little collection can remain precise and clear.

Evn if such pictures had found their way onto one large canvas, the chaos of the endless connections between the images would still have been fitting; a kind of expression of urban chaos. Walser’s own satire of bureaucratic order simultaneously doffed its cap to it and whispered curses upon it when its back was turned. I imagine making the work was rather like the process of finding Walser’s infamous microscripts and turning them into cognisable books for people to read. These are equally images to be read as well as seen.

Walser once wrote that ‘We don’t need to see anything out of the ordinary. We already see so much.’ His writing was a rebellion found in taking a radical notice of things, acknowledging the forgotten and the taken-for-granted things that slip by every day in our rushing to be behind the desk. In Berlin and the Artist, Dean harnesses that same curiosity in collating ephemera, assumed to be lost (or given no thought at all) and lifts it out of the white noise of history. In doing so, she not only creates a work that is in the spirit of Walser but also a work that revels in that same sense of joyful accident.