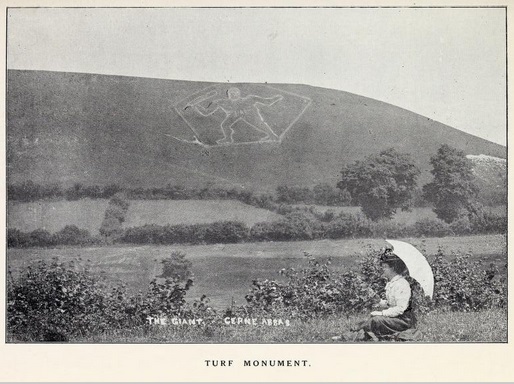

A naked man lies on a Dorset hill whilst another is painting him, quickly. Eric Ravilious is on a fleeting trip to just north of Dorchester and the war, already broken out, is on his mind. He paints the man, the land around and the humanity of the hills, quickly. The man is the Cerne Abbas Giant, a mysterious earthwork of a primitive man with club and erection, dug into the land and filled with chalk. The disputes around the man are unnecessary. Whether a genuine article of Neolithic expression or a satire mere centuries old, the man taps into something of the folklore and spirit of the land; that of fertility, livelihood and the simple pleasure of living. Ravilious is, at this point, a relative success with his various designs finding their way onto Wedgewood pottery and he is soon to become an official war artist, sent to sea to paint cruisers in Norwegian seas attempting to fend off the Luftwaffe. But, before all of this, Ravilious attempts to find England, to emblazon a memory of something to fight for. He goes to Dorset to see the giant.

Ravilious’ painting is unusual for a landscape painting even in this modern period. Very much like Paul Nash, the turmoil of the century so far has taken its toll on the perception of everything around him. Romanticism is dead and the land is no longer a refuge of unquestioned piety but has other draws; a sense of deep time that even the tumultuous war would struggle to wipe out ultimately. I imagine, when looking at the picture, Ravilious sat with his easel set on the incline of an adjacent Dorset hill, staring at the giant; what is he thinking? At first, so my imagination continues, he must take in the surroundings, acknowledging the topography around him and how, whoever created the giant, knew the canvas of their landscape incredibly well. The hill becomes a mist or even a cloud, the giant imprinted onto it with hard lines, almost as if he’s standing against the sky, ready to walk.

Ravilious could have edited his view, showing the landscape in a falsely pristine condition as artists had done before and after his work. Samuel Hieronymous Grimm would do so in 1790 though, in all likelihood, the landscape was pristine in the eighteenth century. Worse is Frank Dobson’s “See Britain” version for Shell Petrol, exaggerated and cleaned, ready for the cars to flock and park. Ravilious isn’t interested, reality is already crumbling into violent chaos only a year into the true catastrophe of his era. There’s no point in editing, for this landscape as it is, spirit and all, is worth fighting for. He looks out, the giant staring towards the sky with club in hand, and notices that his view is obscured. He has done this before, the year before in fact in his painting of another man of the field, The Long Man of Wilmington in Sussex. The Home Counties, England’s distracted dreaming, cannot escape this reality either. Both men, therefore, are caged. Their landscape is wrapped in the truth of their territorial markers; the barbed wire fences take prescience over them.

The giant seems almost inconsequential to the tatty posts and the sharp metal wire that snakes in front of him. A line of wire even crosses above the Long Man of Wilmington himself, shrinking him in stature just as the metallic violence of coming years did to every man. The fence is the context we must see the painting through. Ravilious offers us no other choice. The giant, however, stands just above the spikes, the violence growing unavoidably out of the land. Our history, even our spirit of place, cannot save us from the impending calamity of the war, so to speak, and Ravilious knows this as the weather of his autumnal day turns. The grass becomes a palette of muted greens and the sky becomes grey but the man stares on. Ravilious leaves, never to return to such places.

He goes to the dock some time later where he joins the Navy and begins to paint their battleships. He moves further away as the war progresses, perhaps more daring in what he paints; battles and confrontations all rendered mysterious. A plane has failed to return from patrol. It is 1942 and Ravilious opts to join the search party. He’s in Reykjavík and flies with the patrol from the RAF base there. Perhaps the mystery of the disappeared plane lights his curiosity. They fly into the haze of the cold horizon and Ravilious, along with the crew, disappear. He is marked as lost-in-action, his body never returned. It is early morning in Dorset, so I imagine, and the giant stares towards the sky once more as the dawn sun sends shards of light glinting off the man-made thorns of the wire that bloom all around him.

I once knew a chalk man,

A giant, so to speak,

Who stared into the sky,

In search of his friend.

The giant man knew that the field,

All the fields around, in fact,

Were not tidy.

His visitors denied it,

Rewriting his home,

But his friend could not, would not,

Bring himself to commit such lies.

The sky is moon-grey,

The same grey as the day,

When,

With a feeling of mourning,

The giant knew that his friend,

The man who, alone, could see the barbed wire,

Was lost.

Wonderful – thanks for posting this. I’ve always liked the fact that Ravilious paints the giant on a line parallel to the wire, but which disappears into the distance. The effect for me is that the barbs become stars – the giant becomes Orion striding over the Milky Way. But I’m an optimist 🙂

.. and it also might be because of his similar treatment of stars in The Twelve Designs Engraved on Wood (Almanack 1929)

“The disputes around the man are unnecessary. Whether a genuine article of Neolithic expression or a satire mere centuries old, the man taps into something of the folklore and spirit of the land; that of fertility, livelihood and the simple pleasure of living.”

Excellent point.