As tradition dictates, the following is a round-up of all the year’s viewing, reading and working. 2025 has been a somewhat tricky year and I’ve decided to not be quite so exhaustive in writing up the detail of my viewing in particular, not least because the quality of films has been somewhat lower than previous years. Juggling the requirements of my work with a few big changes personally, the reality of watching more challenging work (and daily as well) meant I’ve simply not wanted as in-depth a viewing schedule this year. In spite of that, 188 films have been watched, along with 40 TV series, and 48 books have been read. So, to the matter in hand.

Films

This year’s film viewing has been dominated by British film. Having concentrated on it for so many years, I honestly thought there was little left that could surprise. How wrong I was. Britain has a few films in my final ten which I hadn’t heard of before this year (while many of the later-mentioned films have been on various lists for a while).

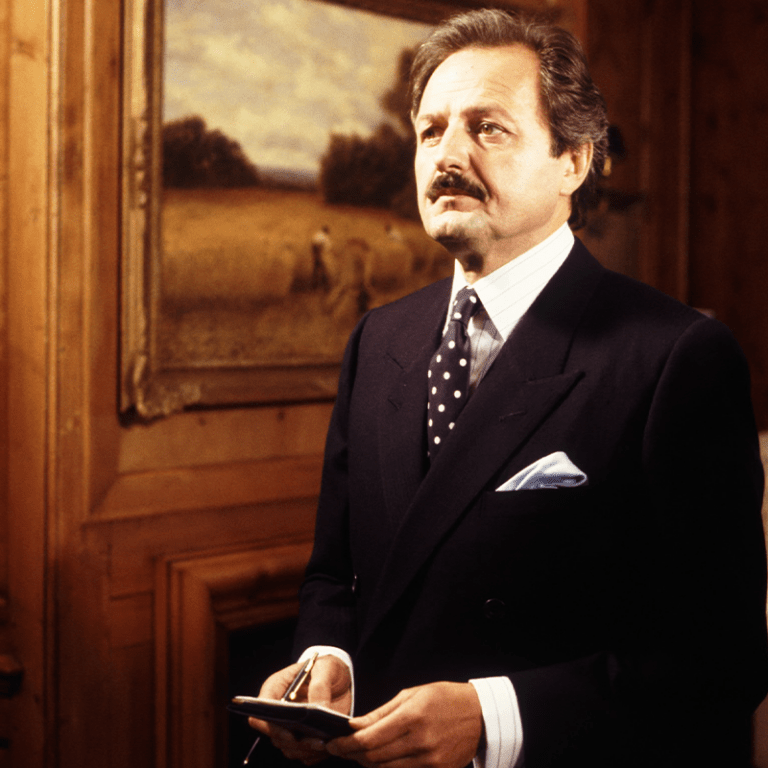

The most obvious example of this is Michael Anderson’s Conduct Unbecoming (1975). A film not very well rated, this very theatrical drama following allegations of an attack on a woman at a military camp in colonial India managed to surprise at every turn. It helped that it was driven by a stunning ensemble cast, Richard Attenborough especially leading the way. I think it deserves a far better reputation.

This year I began exploring 1980s British cinema for proper. In the past, I’ve been a little dismissive about the shifts and changes in this decade of our national cinema, put off by the pristine period drama to unbearably preachy grit and grim binary of the decade. But there was plenty that bucked that trend. In my top ten, this is represented by the stunning The Dresser (1983) by Peter Yates. I love behind-the-curtains dramas and this one following a dying Shakespearean and his dresser ticked all the boxes. Tom Courtenay gives the performance of his career as the spurned dresser whose loyalty is heartbreakingly disregarded by Albert Finney’s uncaring thesp.

The Dresser and Conduct Unbecoming had some competition from other British films. Alan Bridges’ The Shooting Party (1985) was a lovely autumnal slice of melancholy period drama and made me want to seek out Isabel Colegate’s original novel. Colin Gregg’s We Think the World of You (1988) surprised me considering its poor reputation (in comparison to its source book at least), though this year has taught me that IMDb users generally have bad taste in British film. Anthony Pelissier’s The Rocking Horse Winner (1949) was a great little gem from the Ealing canon that I’d saved for a while. Richard Lester’s Juggernaut (1974) scratched an itch not satiated since watching Ffoulkes, and Alvin Rakoff’s The Comedy Man (1964) showed how Kenneth More could, unusually, do quite a good Angry Young Man kitchen-sink feature, even if neither young or angry when filming it.

From British cinema more generally, I also enjoyed The Secret Partner (1961), Rattle of a Simple Man (1964), A Month in the Country (1984), To Sir, with Love (1967), The Night My Number Came Up (1955), The Wrong Arm of the Law (1963), The Ship That Died of Shame (1955), Scott of the Antarctic (1948), A Night to Remember (1956), Unman, Wittering and Zigo (1971), The Galloping Major (1951), The Killing of Sister George (1968), Sebastian (1968), Another Country (1984) and Code of Scotland Yard (1947). I’d name the directors but the list is too long.

American cinema was also firing on all cylinders this year. William Wyler’s The Heiress (1949) easily stormed into my final ten with a superbly brutal adaptation of Henry James. Olivia de Havilland was brilliant, but it was especially nice to see a more unusual role for Montgomery Clift as the money-grabber trying to worm his way to fortune. Classic Hollywood has provided a wealth of pleasure, frankly. Edward Dmytryck’s Mirage (1965) was a beautifully shot paranoid thriller in a similar vein to John Frankenheimer’s work, and allowed Gregory Peck some room to manoeuvre beyond his usual straight-laced good guy. I filled in some excellent Sidney Poitier gaps, including the joyous Lilies of the Field (1963) by Ralph Nelson and the visceral The Defiant Ones (1958) by Stanley Kramer (Poitier truly highlights what a loose cannon Tony Curtis was as a performer in this period) to go alongside the earlier mentioned To Sir, With Love. America also provided the best thriller of the year in the form of James Bridges’ The China Syndrome (1979). A great realist thriller, it had undertones of the future BBC series Edge of Darkness, but with Jack Lemmon playing a rare, serious role (superbly).

American films I also enjoyed included All the King’s Men (1949), The Misfits (1961), Possessed (1947), Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), The Swimmer (1968), Fat City (1972), Nobody Lives Forever (1946), All My Sons (1948), Kill Her Gently (1957), The Fortune Cookie (1966), My Man Godfrey (1957) and No Way To Treat A Lady (1968). Again, too many directors to detail but all are worth looking up.

Where cinema really sparked for me this year was when dealing with war. From Here to Eternity (1953) by Fred Zinnemann was the best, with several levels of drama, some amazing set-pieces and beautiful character studies. Seeing the triple of Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift (again) and Frank Sinatra raised the film to the heights of a classic. Other war films enjoyed included Leslie Norman’s Dunkirk (1958), Lewis Milestone’s Pork Chop Hill (1959), Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One (1980) and Robert Wise’ Run Silent, Run Deep (1958). Evidently Lancaster has been a cornerstone of films this year as well (probably my favourite Hollywood leading man of the fifties and sixties).

In the most American terms of cinema, I’ve enjoyed a handful of Westerns. The best was Day of the Outlaw (1959) by André De Toth. This was one of the last really big classic Westerns I still had to see and it didn’t disappoint. It was quickly added to the list of majestic snowy Westerns. Alongside this, Fastest Gun Alive (1956) by Russell Rouse and Support Your Local Sheriff (1969) by Burt Kennedy were also decent, differing examples of the genre, though this was pretty much where the buck stopped, having watched endless examples of the genre over the years.

Moving to Italian cinema, it more than held its own against its English language counterparts. I was heavily drawn in by The Most Beautiful Wife (1970) by Damiano Damiani which was an excellent Mafia film focussing on a vaguely Me Too-ish narrative that worked incredibly well. However, the strongest Italian film of the year was easily the deeply disturbing The Damned (1969) by Luchino Visconti. The film had the director’s usual maverick lusciousness, yet applied to the rancid rise of Nazism in one industrial family. The sequence detailing the Night of the Long Knives will stay with me for a very long time, as will Dirk Bogarde and Ingrid Thulin’s astonishing performances.

Plenty of other Italian films entertained beyond disturbing dramas such as these. Antonio Pietrangeli’s I Knew Her Well (1965) fulfilled the Antonioni-shaped hole in my life; Ettore Scola’s We All Loved Each Other So Much (1974) was a perfect, witty example of Italian satire with an amazing re-run of Fellini and Mastroianni (playing themselves) filming the fountain sequence in La Dolce Vita; Fernando Di Leo’s Rulers of the City (1976) was a note perfect example of Poliziotteschi cinema; and Elio Petri’s We Still Kill the Old Way (1967) was a beautifully photographed intelligent thriller that allowed Gian Maria Volonté to get his teeth into another typically complicated role.

French cinema also had a few hits here and there. The best was genuinely very good in the form of Claude Zidi’s My New Partner (1984). The film further confirmed for me that France’s greatest actor, in terms of pure acting skill, is easily Philippe Noiret (helped further this year by Claude Miller’s Very Happy Alexander (1968)). I have a bad feeling these may be the last classics I have to watch with him in but hoping a few more may be in the woodwork. Someone please give him a statue on a boulevard somewhere. I also enjoyed Claude Sautet’s Vincent, François, Paul and les autres (1974), Robert Hossein’s Le goût de la violence (1961), Claude Pinoteau’s La 7ème cible (1984), Claude Miller’s Dite-lui que je l’aime (1977) and Jean Delannoy’s The Little Rebels (1955).

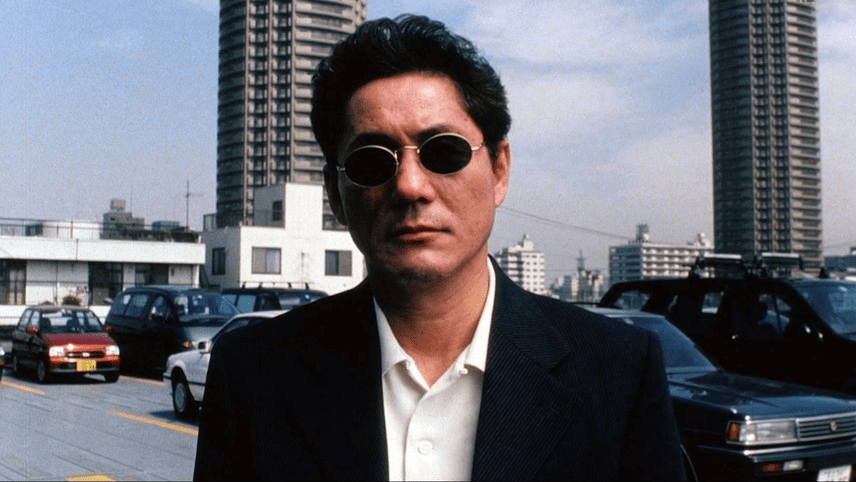

As in most years of my viewing of late, Japanese cinema was heavily represented. The best (and again this has become a trend) was Fireworks (1997) by Takeshi Kitano. Its cold, unforgiving atmosphere is typical of Kitano, but it also had the mature patience that was sometimes missing from his earlier, showier films. Japanese crime cinema produced a wide range of incredible viewings including Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity (1973), Takashi Nomura’s A Colt is my Passport (1967), Yasuzō Masumura’s Black Test Car (1962), Takumi Furukawa’s Cruel Gun Story (1964), and Koreyoshi Kurahara’s I Am Waiting (1957).

I also loved Nagisa Ōshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), which is one of the strangest but haunting war films I’ve seen, Masahiro Shinoda’s Pale Flower (1964), which has the usual qualities of Japanese classical noir, and Toshiya Fujita’s Lady Snowblood (1973), which was beautiful and bloody.

A few films certainly disappointed this year, though mostly due to my high expectations. James ivory’s Maurice (1987) was a massive misfire for me in spite of being stunningly shot. It lacks any real direction or sense of consequential reality for the actions of its lead character, and made him seem reckless to the point of annoyance in the end rather than bravely defying his era. The format of George Sidney’s Kiss Me Kate (1953) was exhausting in that it couldn’t decide what kind of musical it wanted to be (Stanley Donen would have been a great fit for sorting it out). Elio Petri’s Todo Modo (1976) was horrifyingly gorgeous to look at and had a superb ending, but the political landscape it was initially released in renders it crass and a misfire in that typically soap-box radical way that stains some 1970s Italian cinema. Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955) had its moments though is far from the quality of its reputation. And David Leland’s Wish You Were Here (1987) had one of the most annoying characters to lead any film watched this year (and paled in comparison to the much better and similar Hope and Glory (1987) by John Boorman).

However, plenty of bad films were enjoyed this year. I adored the absurdity of the Confessions trilogy, in particular Confessions of a Window Cleaner (1974). I accepted as well that I find the cast of Spice World (1997) arguably superior to many Oscar-winning films of late, while an array of brilliantly bad ninja films such as The Ninja Squad (1986), Ninja Terminator (1985) and Snake Eater II (1989) provided laughs. I also loved The Wild, Wild World of Jayne Mansfield (1968), The Adventures of Hercules (1985), Cat-Women of the Moon (1983) and Raw Deal (1986).

In spite of enjoying all of these terrible films, one went beyond fun and deep into the realm of the painful. Gordon Douglas’ Sincerely Yours (1955) really has no right to exist yet somehow does. It’s a fluff piece to showcase Liberace; on paper something that should be hilarious and camp. Sadly it’s neither. Instead we’re subjected to endless, schmaltzy renditions of classics done badly and a bizarre story which largely revolves around Liberace spying on people in Central Park with a pair of binoculars. It’s a bit like Rear Window, albeit diabolical.

Books

I’ve noticed that my reading this year has been heavily balanced between nonfiction and fiction for the first time. The balance seems to have come from nowhere, though perhaps my own dealings with the publishing of fiction has started to deflect me away from the pleasures of stories. Anyway, the result has been some great nonfiction reads this year, Simon Raven’s The English Gentleman (1966) being the most effective. Largely acting as a biographical springboard for the personal events that any Raven fan will recognise as popping up throughout his novels, the book manages to balance daringly honest self-reflection with an interesting history of gentlemanly traits and tropes. Other nonfiction enjoyed included Jeffery Bernard is Still Unwell (1991) by Jeffrey Bernard (astonishingly good considering he was likely sloshed throughout the entirety of its writing), A Short History of England (1917) by G.K. Chesterton, Selected Writings (Year Unknown) by Samuel Johnson and The Fall of France (Year Unknown) by Winston Churchill.

Talking of Raven, I very much enjoyed his standalone novel Brother Cain (1959) and the Alms for Oblivion novel Friends in Low Places (1965), though neither were quite as strong as the work I read by him last year. Chesterton also produced some fiction work that liked this year, namely The Man Who Was Thursday (1908) which was incredible yet odd.

This year, I’ve tried to surround myself with the kind of fiction I’d like my own work to move towards; largely out of frustrations of the hollow, academised nature of contemporary literary fiction. Evelyn Waugh was my first point of call with the stunning Officers and Gentlemen (1955) and Vile Bodies (1930). His work continues to astound and inspire. J. L. Carr’s A Month in the Country (1980) had a quiet dignity about it without forgetting to be warm and human about our follies, while I found much comedic relief in John Mortimer’s The Trials of Rumpole (1979) and P.G. Wodehouse’s Psmith in the City (1910).

In terms of the previous literary reading habits, the only book worth mentioning is Chris Petit’s The Hard Shoulder (2001). Far superior to the miserablist Robinson (a genre that I’ve found increasingly unbearable of late: Lane, Harrison et al), the novel sped along and had the genuine feel of a crime series. It would make for a phenomenal film.

Talking of crime, this has been a pretty good year for crime novels. The best was easily (once again) by James Ellroy in the second of his L.A Quartet, The Big Nowhere (1988). There are several scenes that refuse to leave me; so visceral, and at times horrifying, is the crime. To be honest, it has a more effective horror atmosphere than most horror that I’ve read for the last few years. I also enjoyed Arthur La Bern’s It Always Rains on Sunday (1945), Agatha Christie’s The Mirror Crack’d From Side to Side (1962), and Seichō Matsumoto’s Inspector Imanishi Investigates (1961), the latter proving that more crime novels would benefit from their murderers killing people with musique concrete.

Another little branch of great reading came this year from finally cracking open several novels that could loosely be called Virago novels; those green-spined, melancholy fictions usually written by women between the wars. The best, and most quietly surreal, was Our Spoons Came from Woolworths (1950) by Barbara Comyns. The novel is difficult to describe though the closest things I can liken it to are either the short stories of Robert Aickman or the paintings of Christopher Chamberlain. I also loved Mary Webb’s Gone to Earth (1917) and May Sinclair’s The Life and Death of Harriet Frean (1922). Perhaps it would be wrong to include Hilary Mantel here but, I bet if she was writing in earlier decades, her novels would have possessed a green spine and a Vanessa Bell-esque painting on the cover. Funnily enough Mantel produced one of my best reads of the year as well as one of my worst. Bring Up the Bodies (2012) was as monumental and glittering as Wolf Hall, while Fludd (1989) was an unmitigated mess. I look forward to finishing her Cromwell trilogy, however.

Genre writing beyond crime has been relatively sparse in between it all. I’ve started working my way through Ian Fleming’s Bond novels after years of putting it off, and I thoroughly enjoyed Casino Royale (1953) and Moonraker (1955). I was especially surprised by the latter which closer resembled a Nigel Kneale Quatermass entry rather than the Bond film that eventually came of it. Ursula K. LeGuin also continued to amaze and surprise, especially A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) and its slightly lesser sequel The Tomb of Atuan (1970). Other than that, the only Sci-fi I read was Burning Chrome (1982) by William Gibson which was total nonsense.

Finally, my best read this year came from the dabbling in the classical canon. I certainly enjoyed Madame Bovary (1856) by Gustave Flaubert and the autobiographical Agnes Grey (1847) by Anne Brontë, but neither compared to The Moonstone (1868) by Wilkie Collins. Collins’ strange crime tale is everything I could ask for in a novel. It weaved between voices and ideas, chilly and conspiratorial atmospheres and pure narrative momentum. I loved it verily while also mourning how such a complex yet narrative driven novel would likely struggle to be published in today’s industry.

Television

Television has been particularly strong this year, not least as it’s taken up the majority of my viewing focus. I started the year with the 1987 John Le Carré adaptation, A Perfect Spy. While flawed in comparison to other 80s Le Carré adaptations, most series would fade in comparison to Tinker, Tailor and the like. Two spy dramas, on the other hand, both made my final ten best series in spite of being dramatically different.

On the one hand was the stifling, tense The Lotus Eaters (1972-73). All the images I’d seen of the series before watching suggested it to be some kind of holiday-in-the-sun jaunt around Crete but its darkness and unforgiving nature quickly surprised me. It may also contain Ian Hendry’s best performance as the drunk, troubled Erik. In stark comparison was Mr Palfrey of Westminster (1984-85). Its chilliness stands in almost total opposition to The Lotus Eaters, and certainly filled the George Smiley gap in my viewing and reading life. Alec McGowen was simply superb; I just wish the series had been triple or quadruple the length.

Political docu-dramas have dominated my viewing this year. The strongest was The Life and Times of David Lloyd George (1981). Philip Madoc was born to play the politician as it charts his whole dramatic life, from riots and war to affairs of state and the heart. Its use of music by Ennio Morricone may be one of the strangest creative decisions I’ve come across this year but overall it works magnificently. I was originally sent to this series, and others, by the brilliant anthology show, Number 10 (1983). My favourites from that were Denis Quilley as Gladstone and Ian Richardson as Ramsey MacDonald, but every episode was great. I also loved Edward & Mrs Simpson (1978), Suez (1978), and Disraeli (1980).

Enjoying these set me up for a string of excellent period dramas. My favourite was the witty, ecumenical wrangling of The Barchester Chronicles (1982). Again, I’d have loved this series to be triple the length, just to enjoy more of Alan Rickman’s Mr Slope battling with Nigel Hawthorne’s Dr Grantly and Geraldine McEwan’s Mrs Proudie. Luckily, I had the hilarious Mapp & Lucia (1985-86) to provide more of the latter two, and with the added addition of the wonderful and sadly departed Prunella Scales. I also had the pleasure this year of the 1974 BBC adaptation of David Copperfield (the best I’ve seen, especially for the coupling of Arthur Lowe and Patricia Routledge) and A Horseman Riding By (1978) which features some wonderful character dynamics, a narrative haunted by war and possibly my casual falling in love with Fiona Gaunt.

The best period drama of the year was ironically not in this costume-ish vein but instead the tensest drama I’ve probably ever watched: namely John Hawksworth astonishing Danger UXB (1979). Following the bomb disposal teams of the Royal Engineers during the Blitz, every episode was better photographed than most of the films watched this year, as well as rich in desperate human drama. Anthony Andrews, the brilliant lead, had just been forced out of The Professionals in place of Lewis Collins. Not only did it do wonders for that series but also allowed the existence of this one, so a great move on all counts.

Danger UXB was a Euston Films production, which turns my attention to those high-budget all-on-film series that I have a love/hate relationship with (I often crave the comforts of interior multi-camera scenes because I’m a little strange). Many such series of the Lew Grade variety were watched in full and, though they work less well when binged, they still provided enjoyment. The photography of both Department S (1969-70) and Man in a Suitcase (1967) blew me away, though both series suffered from samey storylines. Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) (1969) lasted just the right amount of episodes to play with its unique format, while I had great fun with the sheer absurdity of Space: 1999 (1975-77), though its second series was hilariously bad from beginning to end.

I’ve had less luck this year with crime thrillers, having exhausted several rich veins. My favourite was easily the grim and gritty The View from Daniel Pike (1971) which felt a nice tie-in thematically to the crime cinema of the same period. Sticking with Scotland, I enjoyed what remains in the archives of Sutherland’s Law (1973-76). I love these Sunday evening-esque rural dramas, especially when led by someone like the incomparable Iain Cuthbertson (my kingdom for another series akin to Budgie). Sutherland’s had an array of varied stories and themes, in spite of missing so much. I also polished off the remainder of Francis Durbridge’s back catalogue, the strongest this year being the 1964 version of Melissa (better than last year’s 70s version). The only really weak crime drama watched was Fraud Squad (1969) which was mostly pedestrian and not helped by the especially annoying moralising character of Patrick O’Connell’s wife played by Elizabeth Weaver (I want bang-to-rights in my procedurals, not useless sentiment – though it is in hindsight tellingly prescient).

I’ve been trying to identify a name for the kind of wordy adult drama that television used to do so well but has since replaced with either genre series or BBC Three-ish Adult-escence nonsense. The best of these much better series aimed squarely at the adult audiences of yesteryear was undoubtedly Hadleigh (1969-76). I already loved Gazette last year, and Hadleigh didn’t disappoint. Gerald Harper continued to be sublime, while the sheer range of drama for the country gent surprised and confounded. The only criticism was the needlessly hostile character of Jennifer (Hilary Dwyer) who was a misfire in the third series. But, otherwise, a wonderful series on all other counts.

Talking of gentleman, I really loved Lytton’s Diary (1985-86), largely because of the dependable Peter Bowles. I lapped up its early 80s sleaze and glamour, and it even managed to escape its initial stumble of Rick Wakeman’s opening theme music. Also in my viewing was The Plane Makers (1963-65) which I watched in the hope it would live up to its sequel, The Power Game (1965-69). Certain episodes of it certainly did, though its many shop-floor union episodes were deadly dull compared to the board-room shenanigans (the sequel gets it so right). Staying in the same area, I also enjoyed Man at the Top (1970-72), a series again dealing with the double-dealings of the boardroom. However, it required shutting out the unbearable hypocrisy of its lead character, John Braine’s Joe Lampton, in regards to sex, but it worked really well beyond that.

My comedy viewing somewhat wavered this year, largely because it was so dominated by one show: Steptoe & Son (1962-74). The writing of the series was phenomenal and the political dynamic between the two leads was especially entertaining and poignant. However, it did somewhat stretch itself thin over the many series, and verged, on occasions, into utter ridiculousness (in contrary to the entertaining subversion of kitchen-sink realism in its earlier episodes). Virtually every episode contained some laugh-out-loud moment, however, which is more than can be said for every modern comedy I’ve been put through of late. On that note, I also watched To The Manor Born (1979-80) which I weirdly enjoyed in spite laughing approximately twice. Again, Peter Bowles was the main reason to watch.

Viewing was thin this year on the genre front, beyond those earlier high-end series. I very much enjoyed Philip Mackie’s An Englishman’s Castle (1978) in spite of its hysterical approach to politics, while Shades of Darkness (1983) had a few nice moments though reminds of how unique Lawrence Gordon Clark is in his ability to actually film ghosts effectively (no one else has come in any way close; it’s a dark secretive art long since lost). And Object Z (1965) was absurd fun and in no way should be taken as seriously as it takes itself.

Finally, I watched a bizarre array of non-drama television (nonfiction?). The weirdest of these viewings was a tie between The Adventure Game (1980-86) and Cooking Price-Wise (1971). The former is, perhaps, the strangest game show ever made, with an infuriating but entertaining splice of The Generation Game and Blake’s 7, while the latter is Vincent Price’s pet cooking project which may contain some of the most disgusting and vile images of food ever assembled. However, the highlight was undoubtedly Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation (1969).

Civilisation is one the best things I’ve ever seen. I felt a full paradigm shift occurring within as its beautiful visuals, effective arguments and peaceful strength was showcased each episode. I recall even cheering at the end of its penultimate episode with Clark’s polemic against the flaws of modernity. I also recall, in my naïve days, when I hopelessly got through to the competitive round of the BBC’s New Generation Thinkers shceme, clips from it were shown deliberately as an example of bad, slow academic presenting. A typical coterie of performative young academics dug into Clark, while praising to the hilt the modern, disposable pretenders. Even then, it felt off (and I did note a pleasing correlation between how insufferable the candidates were in their opinion of Clark and who eventually got chosen from my group in the final ten). The modern clips they so adored were empty shells chasing internet audiences, nothing more. If the recent Civilisations is anything to go by, the lessons still aren’t being learned. But, in hindsight of watching Clark in full, it diagnosed all current documentary problems, and happily mapped the cul-de-sac they’ll likely never escape from.

My Work

This year has been a little strange for me writing wise. I’ve worked almost constantly on commissions, especially researching location work, but have felt like I’ve had fewer jobs than any other year; the ones I did get were fought for tooth and claw. I’ve had a book released but really very little happened with it. And I’ve done a fair few public facing events and things, but honestly can’t remember a single thing about virtually any of them, especially in regards to anything actually coming from them.

In regards to freelance work, my location visits have taken me all over the place, from Paris to Rome, via Derbyshire, Cardiff, London and endless fields and estates in between. I’ve also managed to crack a few new publications to replace the older ones who don’t email back anymore. Here are ten articles I’ve been really happy with this year.

- Five Locations from Wings of Desire (BFI)

- Why Terence Rattigan Deserves a Cinema (The Spectator)

- Out of the Unknown and Black Mirror (BBC Culture)

- Endings: Akenfield (Sight & Sound)

- Five Locations from The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue (BFI)

- The Daredevilry of Jean-Paul Belmondo (BBC Culture)

- The Wirral of The Magnet (BFI)

- The Cars of Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (Private Motor Club)

- Lost & Found: Freelance (Sight & Sound)

- Five Locations from Roman Holiday (BFI)

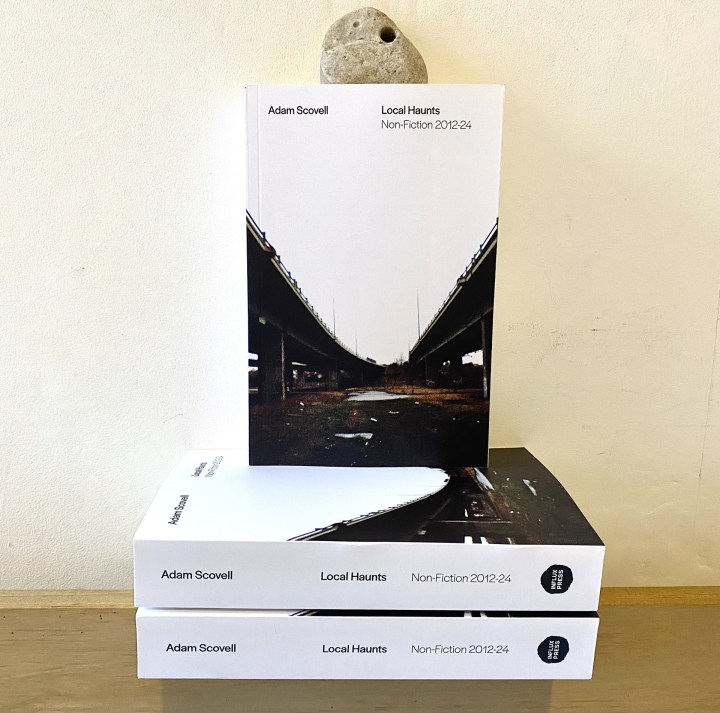

In March, I had my fifth book published in the form of Local Haunts. The response, of what there has been, has been really positive. However, it did really put the nail in the coffin in regards to optimism as to how publishing works. I tracked a similar nonfiction book released the same week as mine, crunched some stats on it and worked out that, aside from the insider handing over of books to various promotion opportunities, the reality is that any book likely needs a prize nomination, a tour of at least fifteen or so events (I had three), or a lot of promo money for it to actually reach an audience. Still, I’m happy with the book itself and glad it was the brilliant Influx Press who put it out as no one else has really bothered (and I mean really; an agent has been trying to sell a novel of mine for around eight months and fiction publishing has made it clear that it just sees me as a problem).

This aside, I made a little trailer for a fake edition of J.G. Ballard’s Crash, I’ve done a few front-facing slots here and there including on the Doctor Who Season 7 blu-ray documentary Terror of the Suburbs, I’ve interviewed a few interesting people, including Charlie Brooker and Ramsey Campbell, and I’ve started a Substack for my writing on tailoring in film, music and culture in general called On the Row. I have a rather bad feeling that next year may be my last in doing this kind of work as most doors are now closed or are in the process of closing, but we shall see in 2026.

Many thanks for your support, it is very much appreciated, and wishing you all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.