It’s that time of year once again when I look back on everything I’ve watched and read (and wonder whether I should really get out more). While my interests have become a kind of prison, I couldn’t hope for a more entertaining one. So, here’s my review of 2023. Thank you for reading my work throughout the year, wherever you may have seen it.

Cinema

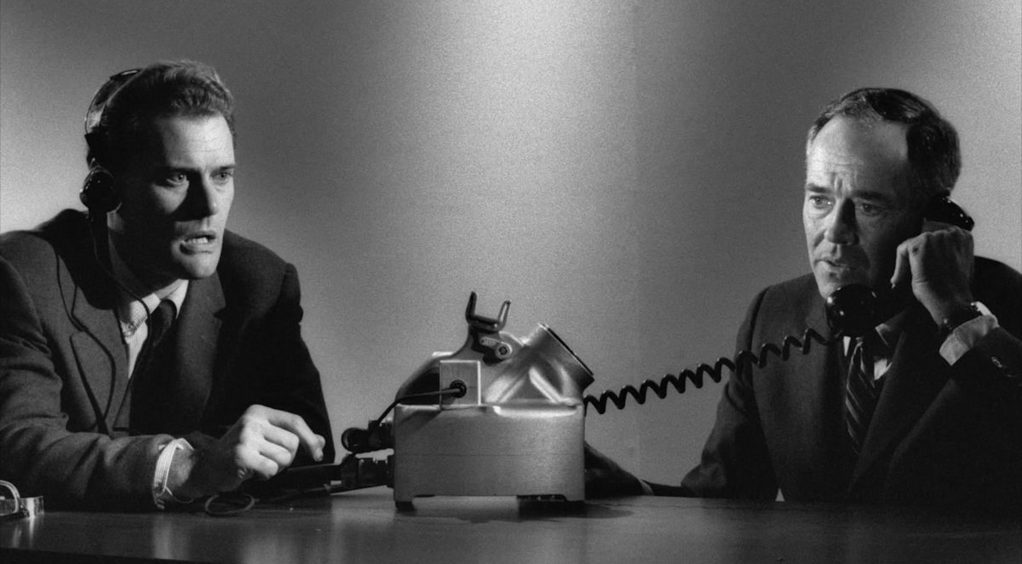

Fail Safe (1964) – Sidney Lumet

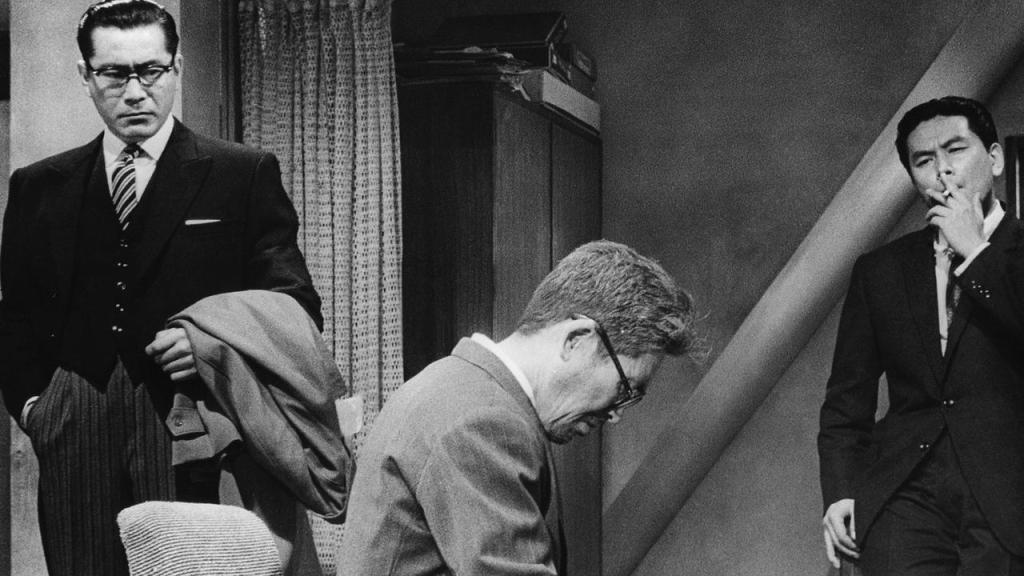

Mafioso (1962) – Alberto Lattuada

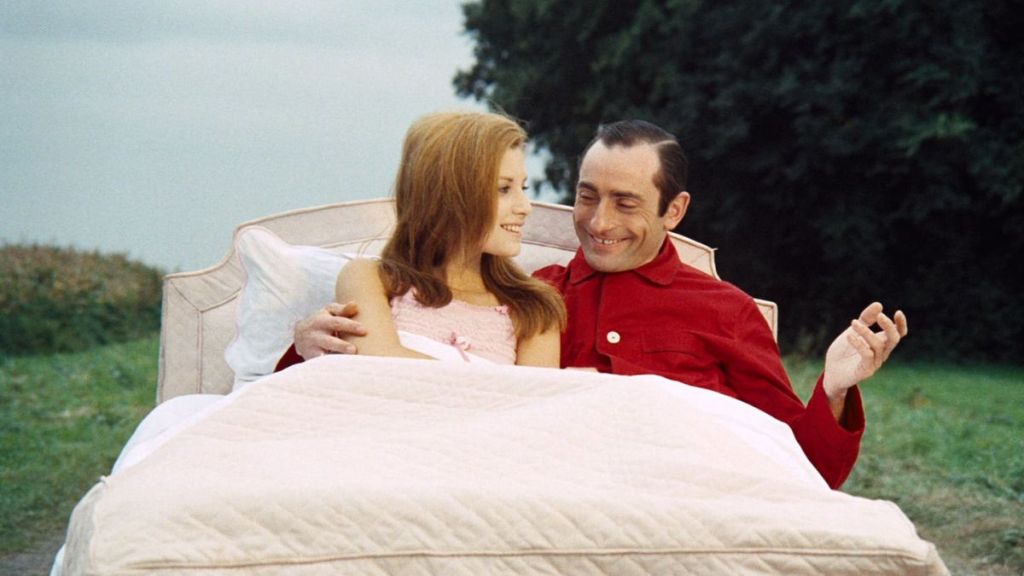

A Sunday in the Country (1987) – Bertrand Tavernier

Marcello Mastroianni: I Remember (1997) – Anna Maria Tatò

Party Girl (1958) – Nicholas Ray

Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) – Mario Monicelli

Father Goose (1964) – Ralph Nelson

Samurai Rebellion (1967) – Masaki Kobayashi

The Card (1952) – Ronald Neame

No Way Out (1987) – Roger Donaldson

As predicted last year, this year’s film viewing ended up being dominated by Italian cinema. Out of the 260 or so films I managed to watch, a fair amount of the best ones were Italian.

The Italian take-over begins in my top ten with Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal in Madonna Street (1958). The film is one of those high quality, big name crime capers with a huge amount of wit, beautiful visuals and a glorious ironic end; a kind of Italian take on an Ealing Comedy. I can’t think of a film I enjoyed more this year. By the same director, I also enjoyed The Organizer (1963). Featuring a barnstorming performance by Marcello Mastroianni, the film looks determinedly at the political naivety of the activist class and their lack of understanding of the very people they often claim to be helping. It lacked the humour that edged Madonna Street ahead, however, but was still a great film all the same.

I also enjoyed an array of gritty Italian thrillers, namely Francesco Rosi’s The Mattei Affair (1972), Damiano Damiani’s The Day of the Owl (1968) and The Case is Closed, Forget it (1971), and Alberto Lattuada’s Mafioso (1962). The latter in particular reminded that there are still a great many classics starring Alberto Sordi to watch; a fun task for the New Year ahead I’m sure.

In terms of other Italian films, the more canonical were few and far between though I loved the splendour of Luchino Visconti’s Senso (1954) and the starkness of Ermanno Olmi’s Il Posto (1961): two highly contrasting Italian films if there ever was a pair.

The best documentary I watched this year was also Italian: namely Anna Maria Tatò’s Marcello Mastroianni: I Remember (1997). It was a lengthy, deeply personal exploration of the actor’s long and varied career, and made me wish that similar stars had been given the opportunity to discuss their lives in such a detailed and free manner.

Documentary cinema in general has been surprisingly strong this year. One of the few genres of film left where I break back into the digital world, a number of films surprised and entertained. Namely, they were Matt Tynauer’s Valentino: The Last Emperor (2009), Alexandre Moix’s Patrick Dewaere: My Hero (2022), Cyril Leuthy’s Godard Cinema (2022) and Patrick Montgomery’s The Compleat Beatles (1982).

Mention of The Beatles reminds that this year has been a strong one for British cinema. It admittedly has an advantage over others in that it doubles as a pleasurable comfort blanket of sorts thanks to casts being so familiar, especially when combined with my television viewing. Classic British cinema, when taken alongside older television, is really like having your own personal rep theatre to hand and rarely disappoints.

The best British film this year was undoubtedly Ronald Neame’s The Card (1952). Alec Guinness was never better than as the charming rogue here, and the film spurred me on a Neame-themed viewing week. The director’s The Man Who Never Was (1956) came close to breaking into my final ten as well, with its wonderful drama following Operation Mincemeat in World War Two.

Another British film that could have made the final ten was The Magic Box (1951) by the Boulting Brothers. I’m struggling to think of a film that has ever assembled a better cast, and it was a worthy screen celebration for the Festival of Britain that year. Robert Donat will always be a favourite and my enjoyment of him here led to filling in a few gaps in his filmography, too, namely Alexander Korda’s Vacation from Marriage (1945), with him playing opposite the magnificent Deborah Kerr, and King Vidor’s The Citadel (1938).

Of the remaining British films watched, the best of the crop were Carol Reed’s Penny Paradise (1938), Peter Ustinov’s School for Secrets (1946), Gordon Parry’s Bond Street (1948), Muriel Box’s Street Corner (1953), Ralph Thomas’ The Vicious Circle (1957), Val Guest’s Jigsaw (1962), Wolf Rilla’s The World Ten Times Over (1963), John Guillermin’s Guns at Batasi (1964) and Sidney J. Furie’s The Leather Boys (1964).

Sticking with English language cinema, this has also been a very strong year for American cinema. Perhaps the most unusual choice in my final ten, and the most modern fiction film, is Roger Donaldson’s No Way Out (1987). Heading into it with a fair degree of cynicism, having loved the previous adaptations of the story in John Farrow’s The Big Clock (1948) and Alain Corneau’s Police Python 357 (1976), I was expecting little. However, it took me completely by surprise and it’s genuinely one of the most intelligent thrillers made in the 1980s.

Following on from my enjoyment of that, I decided to fill in some 1980s neo-noir gaps. Not all hit the mark, but those that did were Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat (1981), Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo (1980), John Flynn’s Best Seller (1987) and John Frankenheimer’s underrated 52 Pick-Up (1986).

In general, this has been another excellent year for noir. When has there ever not been a good year for film noir? The back catalogue of quality films is thankfully endless. The best to make my final ten was easily Nicholas Ray’s superb Party Girl (1958); a full colour, sleazy fifites classic. Other great noirs included Jean Negulesco’s The Mask of Dimitrios (1944), Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Somewhere in the Night (1946), Robert Rossen’s Johnny O’clock (1947), Robert Siodmak’s The File on Thelma Jordan (1949), Fritz Lang’s The House by the River (1950), William Diertele’s Dark City (1950), John Sturges’ Mystery Street (1950), Stuart Heisler’s Storm Warning (1951), and Phil Karlson’s The Phenix City Story (1955).

Of other American films, only a handful were non-Noir. The two that most stuck out (and the two that made my top ten in the end), were Sidney Lumet’s Fail Safe (1964) and Ralph Nelson’s Father Goose (1964). Both are dramatically different takes on war considering they were released in the same year. Lumet’s is arguably the tensest film I’ve watched in years and it’s sad that it has been overshadowed by Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964). Its ending is unforgettable and the best of the year by far. It was also lovely to see Cary Grant in a more unusual role in Father Goose; a perfect Sunday afternoon film if ever there was one.

Out of other national cinemas, the other two that have figured heavily have been those of Japan and France. Both are represented once in my final ten, with Masaki Kobayashi’s Samurai Rebellion (1967) and Bertrand Tavernier’s A Sunday in the Country (1987). As is clearly a pattern to my viewing, after I’ve watched one decent film by a director, I attempt to double it up. In Kobayashi’s case, that resulted in the excellent Inn of Evil (1971), while in Tavernier’s case (perhaps my favourite directorial discovery of recent years), that resulted in Let Joy Reign Supreme (1975).

In fact, Japanese cinema this year has hit particularly hard, especially as I dug into some back catalogues that I thought I had finished. Gems from this search included Akira Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well (1960), Yasujirō Ozu’s The End of Summer (1961) and a double of Kihachi Okamoto films: Sword of Doom (1966) and Samurai Assassin (1965). I look forward to diving deeper into more classical Japanese cinema that I’ve missed in 2024.

For France, the number of classics was slim. Having dived so deeply into its post-war cinema in particular over the last few years, I’m really starting to run out of solid hits. A few still slipped through this year though, namely Jacqueline Audry’s Olivia (1951), André Cayatte’s Tomorrow is My Turn (1960) and Pierre Étaix’s Le Grand Amour (1969). My fingers are crossed for hitting a new vein of older French cinema soon as I miss getting excited about it.

This October, I finally managed to sustain a full “31 Days of Horror” as prescribed by the hashtag, sometimes called Shocktober. In previous years, I’ve used this to fill in a few horror gaps and this year actually managed to showcase a good few classics, in spite of previous years being mostly a completist exercise in particular subgenres and directors (meaning watching total trot).

This October, however, was filled with brilliant little films. Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s The House that Screamed (1969) has stayed with me for a long while and was one of the best shot films watched throughout the whole year. I look forward to watching more by him, in particular Who Could Kill a Child? (1976). I loved Franco Rossellini’s The Possessed (1965), as well; a film that is basically what would happen if Antonioni directed a proto-Giallo. I also enjoyed John Hough’s hauntological The Legend of Hell House (1973), Pete Walker’s glorious House of Mortal Sin (1976), Arthur Crabtree’s fun Horrors of the Black Museum (1950) and Alan Ormsby and Jeff Gillen’s grimy Deranged (1974). Bring on Shocktober 2024.

And finally, the year wouldn’t be complete without my weekly terrible film watch. While no doubt the enjoyment of many of these films was arguably enhanced by copious amounts of booze (I don’t think I was sober for a single one), I’ve had just as much fun with the following films as any of the classics listed above. Namely, I had a good time with David Askey’s Take Me High (1973), Paul Leder’s Ape (1976), Quentin Masters’ The Stud (1978), Corey Allen’s Avalanche (1978), Jon Turteltaub’s Think Big (1989) and Steven Seagal’s On Deadly Ground (1994).

Ruggero Deodato’s terrible The House on the Edge of the Park (1980) is where this film run-down will close, if only for having the funniest death scene I think I’ve ever watched. Here’s to another year of cinematic classics, underrated flicks and, of course, absolute total nonsense.

Books

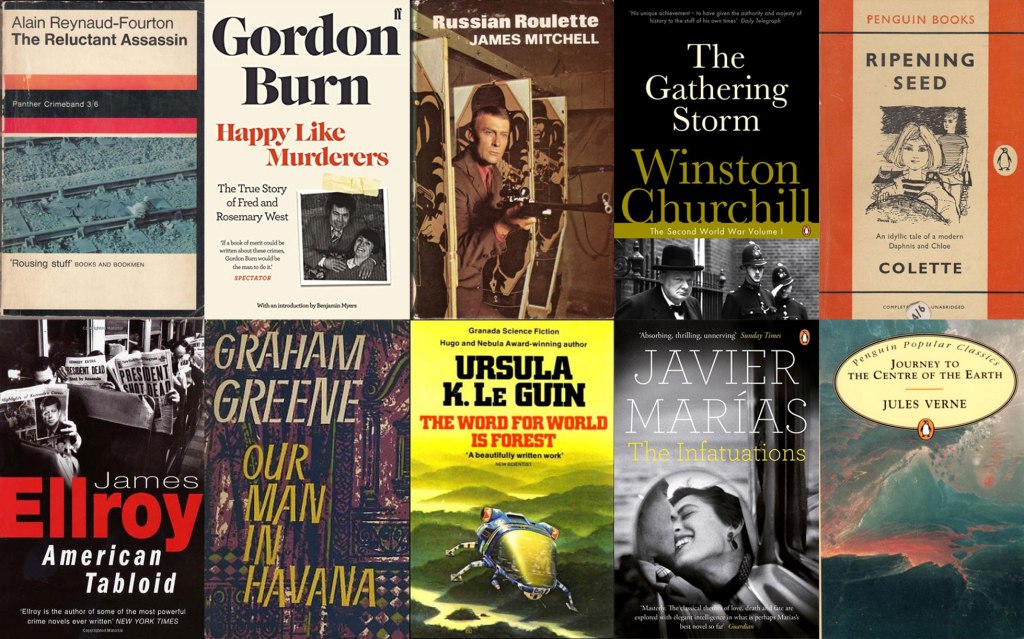

American Tabloid (1995) – James Ellroy

The Word for World is Forest (1972) – Ursula K. LeGuin

Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864) – Jules Verne

Our Man in Havana (1958) – Graham Greene

The Infatuations (2011) – Javier Marías

The Gathering Storm (1948) – Winston Churchill

Happy Like Murderers (1998) – Gordon Burn

Russian Roulette (1973) – James Mitchell

Ripening Seed (1923) – Colette

The Reluctant Assassin (1964) – Alain Reynaud-Fourton

This year’s reading has been marked by the sheer brilliance of crime fiction (yet again). Roughly every other year, several crime novels hit home and make me see the genre in a whole new light all over again.

The revelation this year came in the form of James Ellroy, someone who has always been at the back of my mind because of the excellent screen adaptations of his work. Yet, I’d never properly read him until this year. The best book of the year for me was far and away Ellroy’s American Tabloid (1995). Never has a novel for me so brilliantly captured the horror of ideological violence, while never forgetting that its characters are rounded human beings and not cartoons. As I saw someone else comment about it online, it’s as if several volumes of American political history had been condensed into a 600-hundred page pot-boiler noir. Equally, Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia (1987) should have really been in my final ten of the year in hindsight as well. Both books blew away every other, supposedly more “literary”, book. He could write most Booker nominees out of the room, but we all know that already.

There were a couple of other great American noirs that sparked in between the Ellroys. James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity (1936) breezed by, though rightfully sits in the shadow of Billy Wilder’s more detailed film adaptation (thanks to Raymond Chandler, of course), while Don Carpenter’s Hard Rain Falling (1966) surprised with its transgressive (for the time) subject matter and raw rhythm.

The majority of the crime I read, however, was actually French. Though the year got off to a shaky start with Frédéric Dard’s decidedly average The Wicked Go to Hell (1956), a number of Gallic classics littered the reading year. The best was undoubtedly the little-known thriller The Reluctant Assassin (1967) by Alain Reynaud-Fourton, which subsequently inspired some of my own writing on the current draft of a crime novel I’m working on. It’s a taut, intelligent thriller with a brilliant series of betrayals and the cool, laconic atmosphere of a Melville film. Trying to track down its film adaptation by Jacques Deray is, however, proving more than a little tricky annoyingly.

Other French crime novels enjoyed included Léo Malet’s Mission to Marseilles (1947) – sadly my last in the translations of Nestor Burma’s adventures published by Pan in the 1990s – Jean-Patrick Manchette’s nasty The N’Gustro Affair (1971), Fred Vargas’ An Uncertain Place (2008) and This Night’s Foul Work (2006), and Pierre Lemaitre’s The Great Swindle (2013). It must be said, though, how Lemaitre’s book won the Prix Goncourt is an utter mystery to me.

Interestingly, British crime this year has been dominated by non-fiction, or at least fiction with a hint of real life in it, similar to Ellroy’s. This was largely thanks to Gordon Burn. I’m not sure whether “enjoy” is the right word for his startling Fred and Rose West book Happy Like Murderers (1998) but I know the horrors inside of it will never fully leave me. It was like being locked inside Cromwell Street for the duration. The writing was simply astonishing. Equally, his part fictional Fullalove (1995), while lacking the genius of Alma Cogan (1991), certainly hit the mark, too.

British crime can be a strange beast at times because it veers so heavily in tone. On the one hand, I loved the relentless pessimism of Ted Lewis’ Plender (1971) and Derek Raymond’s Not Till The Red Fog Rises (1994), but equally loved the proceduralisms of R.D. Wingfield’s Frost at Christmas (1987) and Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1987). Both have a place in the genre, and both are endlessly creative.

British thrillers really took off for me this year when doused with a bit of espionage. This is represented twice in my final ten. Graham Greene continues his yearly presence in my best reads with the brilliant Our Man in Havana (1958). Both funny and tense, its humid atmosphere was effectively rendered with Greene’s usual sly humour and menace. James Mitchell made it into my final ten, too, with the third Callan novel I’ve read by him, Russian Roulette (1973). Unlike a lot of 1970s British crime fiction, this actually comes close to achieving that same grim, down-and-out atmosphere created more easily on the screen. In the pulpier arena, I also enjoyed Alastair MacLean’s entertaining Where Eagles Dare (1967), though struggled with his equally famous The Guns of Navarone (1957).

The genre reading continued with a few hints of science-fiction. Only two made my final ten. The first was Ursula K. LeGuin’s beautiful The Word for World is Forest (1972). I struggled to decide whether LeGuin’s The Dispossessed (1974) should be there in my final ten as well, though its admitted laxity regarding political extremism just edged it out for The Word. I also finally read Jules Verne’s fantastic Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864) which, at one point, I forgot was actually fiction. I should also mention Olaf Stapledon’s Starmaker (1937) which did, for a fair chunk of its page count, fall into clunky allegory, but it also had moments of soaring prose and imagery.

In an effort to retain some basic literary sensibility (or at least that prescribed by the industry) I endeavoured to read more literary fiction and classics this year. There were some brilliant rewards, mostly in translation it must be said.

I loved Colette’s Ripening Seed (1923) which perfectly captured the fumbles and naivety of growing pains without falling into the awful clichés and faux-mysteriousness prescribed to most modern coming-of-age narratives.

Desiring a bit of a change, I thought I would dip into Italian and Spanish fiction: both largely unchartered territory for me. Javier Marías’ The Infatuations (2011) was spellbinding; its long weaving sentences achieving a musicality which is so often undeservingly ascribed to much lesser writers. I also dedicated a month to Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605), and certainly enjoyed it. Its first part was, however, undeniably greater than its second, and I was grateful to eventually finish it and move on.

On the Italian front, I loved both Alberto Moravia’s Contempt (1954) and Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958). Contempt was so paranoid and manic that I could hear its narrator mumbling away even when the book was closed and simply next to my bed, while the quiet dignity of The Leopard made it a melancholy treat.

And with that, we come to English literature. In modern terms, I enjoyed Jeremy Cooper’s Brian (2023), a book I liked enough to end up interviewing Cooper twice; once at the wonderful Voce Books in Birmingham, the other for the BFI’s website. I should have also loved M. John Harrison’s The Sunken Lands Begins to Rise Again (2020) but something felt off about it in spite of some effective prose. I think, however, that I will enjoy his “anti-memoir” a lot more which I plan to read in the New Year.

Out of the British classics I read, only a couple hit the mark. Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (1889) surprisingly failed to entertain in spite of a few brilliant deadpan one-liners, as did Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907) which felt bored by its own narrative. The bite of Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop (1938), however, was as strong as ever and Winston Churchill’s The Gathering Storm (1948) is probably one of the best books I’ve ever read, even if its timely detailing of total inaction in the face of growing calamity felt alarmingly prescient. I hope that the other eleven volumes of Churchill’s The Second World War will be just as fantastic, even if the balloon may inevitably go up before I manage to finish them.

Television

The Organization (1972)

Raffles (1977)

Van der Valk (1972-92)

The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (1971-73)

Rumpole of the Bailey (1978-92)

Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years (1981)

The XYY Man (1976-77)

Miss Marple (1984-92)

Three Men in a Boat (1975)

Kavanagh QC (1995-2001)

Before starting on my television viewing of the year, I did want to share some thoughts about the recently defunct Network Releases. Many of my viewing choices over the last few years have been possible thanks to their hard work releasing rare, and sometimes unloved, shows from the vast output of ITV. They took risks that I think no other company would and it’s a crying shame that they ultimately lost out, simply for daring to take British television seriously. My heartfelt thanks to their whole team for making the viewing lives of myself, and no doubt many others, far more interesting than if left to the devices of cowardly modern television executives.

Without Network, I wouldn’t have been able to watch one of my highlights of the viewing year: The Organization (1972). Following the office politics of a very 1970s business, the strangely compelling drama by Philip Mackie was one of those “How did they get this commissioned?” fares, aided by a superb cast led by the silky voiced Donald Sinden. Network also allowed me to binge the entirety of Bless This House (1971-76); perhaps not something to be undertaken by those with a delicate disposition, but an interesting, at times genuinely funny, time-capsule showing almost the precise point when people below the age of thirty-five started being a bit insufferable. Poor old Sid James.

To actual period dramas. Though late in the viewing year, Raffles (1977) is still on my mind. The series starring the wonderful Anthony Valentine as the gentleman thief of society made for perfect autumnal viewing. On the other side of the law, I finally indulged in both series of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (1971-73). A brilliant anthology series that makes the most of its delicious Victoriana, it became gradually addictive until, to my horror, I found I had no more left. Its Carnacki episode starring Donald Pleasence especially left its mark; why it wasn’t picked up as a general series following W.H. Hodgson’s occult detective is beyond comprehension.

This has been a generally good year for detectives of various sorts. I adored every second of Joan Hickson’s Miss Marple (1984-92). I will never for the life of me understand anyone’s aversion to Agatha Christie’s stories, so precise and intelligent are their workings; and this series brought out every single strength within them. In a totally different arena, I loved Van Der Valk (1972-92). Initially put off by the awful theme music (a depressing regular for a vintage Top of the Pops addict like myself), the series surprised in its regular grim crimes and lowlife atmosphere. It may also be one of the few programmes to actually measure the many changes of television over the years and show the differences with one single character: starting with the regular mixture of studio and film, moving to the Sweeney-esque purely film grit, before finally concluding with Morse-form feature length episodes.

I finally also finished Hetty Wainthropp Investigates (1996-98) though, in spite of loving Patricia Routledge, the series’ initial charm soon wore thin as the cases became very similar. I also expected to like Strangers (1978-82) a lot more. Initially, its drama following DI Bulman (Don Henderson) felt uneven as it couldn’t decide whether to be a light-hearted procedural or something grittier. The explanation for this unevenness came when finally watching the far superior, earlier series The XYY Man (1976-77). This series knew exactly what it was supposed to be doing (following a retired burglar used by the secret services for dodgy jobs) but had the Bulman character as a bumbling, comedic foil. Having him in the lead in Strangers clearly meant they couldn’t decide how to play it, though The XYY Man was good enough to make me curious about the other series following Bulman, titled after the character. Maybe I’ll track it down in the New Year.

The year was marked unusually by legal dramas. I worked my way through the entirety of Rumpole of the Bailey (1978-92) which, in spite of generally telling the same story each episode, was a blissful comfort. It’s funny how the habits and rhythms of a character can so carry a whole programme. Equally brilliant, though very different, was Kavanagh QC (1995-2001). Unlike Rumpole, Kavanagh was about the imperfections of the legal system and how they’re something inescapable because the system itself is an expression of human fallibility. It filled the Morse-shaped gap in my life and all but confirmed something I’ve believed for a fair while now: John Thaw is the greatest small-screen actor of his generation.

One of the other best performances watched this year was thanks to the incomparable Robert Hardy in Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years (1981). Supported by an equally phenomenal cast, Hardy cements his screen relationship with Churchill, seemingly almost becoming him while never once falling into the clichés and parody that other performers have over the years. Its brilliant political intrigue also finally led me to read The Gathering Storm so I can be grateful for that as well.

A number of one off television plays hit the mark this year, too. I liked Lawrence Gordon Clark’s ghostly A Pattern of Roses (1983) though missed his more overtly scary ghosts. In my top viewing was Tom Stoppard and Stephen Frears’ adaptation of Three Men in a Boat (1975). As mentioned earlier, the book left me cold mostly, but this version brought out some of the brilliant slapstick moments from the story and was perfectly cast with Tim Curry in the lead. Perhaps the single play to stay with me the most was Dennis Potter’s Moonlight on the Highway (1969). Watched as part of the Dennis Potter at LWT set, Ian Holm’s disturbed and tragic figure worried me throughout the year long after viewing. It’s an utterly heart-breaking play and one of Potter’s best.

Of course, not everything classic hit the mark. It became an eventual slog to get through the many episodes of Ruth Rendell Mysteries (1987-2000), in spite of loving her books and there being one or two standout episodes. G.R. Newman’s Law & Order (1978) tried to be daring in showing police corruption but instead just seemed to endear the viewer to the officer at the centre the drama’s scandal and show how his actions were ironically right. It’s Dark Outside (1964-65) was also weak, though perhaps hampered unfairly by some of its episodes missing meaning that its character arcs fell flat. And, though I enjoyed The Legend of Robin Hood (1975), considering the team and cast behind it I should have really liked it a lot more.

Equally, modern television, something I rarely bother much with anymore, confirmed itself as being mostly disposable. I faintly enjoyed This Country (2017-20) though increasingly found its irony unbearable. I generally enjoyed the all-hands-on-deck attempt by Russell T. Davies to save Doctor Who from certain oblivion and, though it traded heavily (quite effectively it must be said) on the nostalgia factor of its casting, it was mostly good fun. I think the show returning to being regularly on Saturday night was enough to forgive (for now) its handful of weaknesses and unavoidable hubris. Here’s to the Fifteenth Doctor and hopefully a good future for the show.

My Work

It has been another strange year for my own work. It’s the first year since 2016 when I haven’t had a book project to be working on with a publisher (though three are currently in the works off my own bat that I’ll try to find a home for soon).

Having had to put two book projects on here now (something that is ongoing in regards to the longer one, Presence), it has made me wonder whether the last few years were the only time the door was open for me; and the opportunity buggered up by my own mistakes. As new rejections come into the inbox each week, I do wonder how long I have left in the publishing game. It’s a rich person’s arena when all is said and done.

Anyway, general freelance work has kept me afloat and I’ve had, in short form terms at least, three bucket-list commissions. Here are ten articles I’m especially lucky to have worked on this year.

BFI: Ten Locations from Doctor Who

BBC: The Spy Who Came in From the Cold Turns 60

BFI: Five Locations from Don’t Look Now

The Daily Telegraph: Clint Eastwood vs. John Wayne

BFI: Five Locations from The Wicker Man

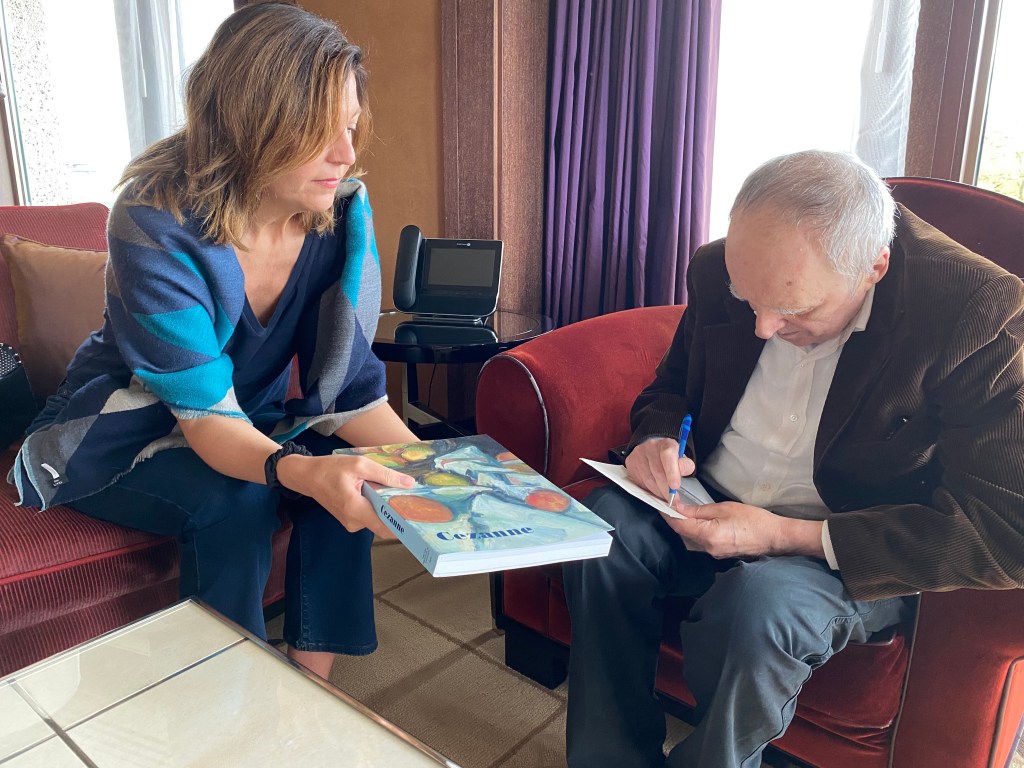

BBC: An Interview with Dario Argento

The Daily Telegraph: Hitchcock’s Favourite Hitchcock

BFI: An Interview with Stephen Volk

BBC: Fellini’s 8 ½ and Cinematic Cool

BFI: Five Locations from A Canterbury Tale

I also managed to have dinner at the Italian embassy held in honour of Dario Argento, I watched this year’s Ghost Story for Christmas (Mark Gatiss’ lovely Lot No. 249) in the editing studio while sat only with its director and producer, I’ve chatted with Terry Gilliam about Fellini while he was stuck in an LA traffic jam, and I’ve managed to go on many, many journeys in search of interesting film locations. I really have no reason to be complaining in the end.

Maybe next year, though, I could have just one success, not even a big one. Just a little one to take the pressure off. Pretty please?

A Happy New Year to you all.

One thought on “2023 Review”