In 1965, Thomas Bernhard bought a house. It was bought roughly between the writing of several works, including Watten (1964) and his second novel Gargoyles (1967). The house is not really house in the ordinary sense, but a collection of farm houses known in German as Vierkanthof. The set of buildings is adjacent to the road of Obernathal in Ohlsdorf near the river Traun which winds down the valleys into Lake Traunsee of Gmunden. Bernhard converted the buildings variously over the years and occupied them during his most prolific period of writing. Many interviews now associated with the man were conducted there and simply searching for pictures of him often brings up images of his house in equal measure.

One suggestion he made was that this house, with its array of rooms and land, was a perfect place to build his ‘memorial dungeons’; a phrase I am still taken with today as it seems emblematic of the writing process more generally. In fact, Bernhard’s Vierkanthof really reflects his own writing process back upon him, somewhat explaining his deathly solitude in the building. The reflection was only for one person.

Once housed in the building, Bernhard would write the following in Gargoyles:

The empty rooms always had a terribly depressing effect upon my father when he considered, he said, that the person who dwelt in them had to fill them solely with his own fantasies, with fantastic objects, in order not to go out of his mind.

The writer here is earnestly detailing his own process, showcasing the construction of the memorial dungeon. Such empty spaces are filled with (and arguably augment) his writing in ways that are clearly discernible; repetitions bouncing off the walls, voices manically filling in the gaps of silence left open by the absence of others, intensive detail of what happens in the lives of people from outside the four walls of a room, the landscape sketched from views almost as if seen from a window. Bernhard’s walls are one of the many restrictions that he placed upon his own writing, resulting in his easily recognised style of layered reductionisms and circular patterns.

I found some photographs of the rooms in Bernhard’s Vierkanthof online last year which is really what sparked my need to write about the Bernhardhaus, simply on an aesthetic level. I was worried that the only way to see photos when initially searching for pictures would be in some digital form, some holiday photos taken on a phone for a travel blog or something similar. Instead, the photographer of the images I found, who now most likely works for the museum that is housed in the building today, very much captured the tone of Bernhard’s prose in all of their austere and aesthetic character.

The first photo I saw was of Bernhard’s writing desk but not a photo actually revealing the desk’s function. A green tint hangs over the empty room, heightened by even greener curtains which drape down to the floor. There appears to be three textures: wood (of the floor and furniture), tiled stone (of the floor below the fireplace) and the general stone of the whitewashed walls. The room in the photo is pristine in its mathematical solitude.

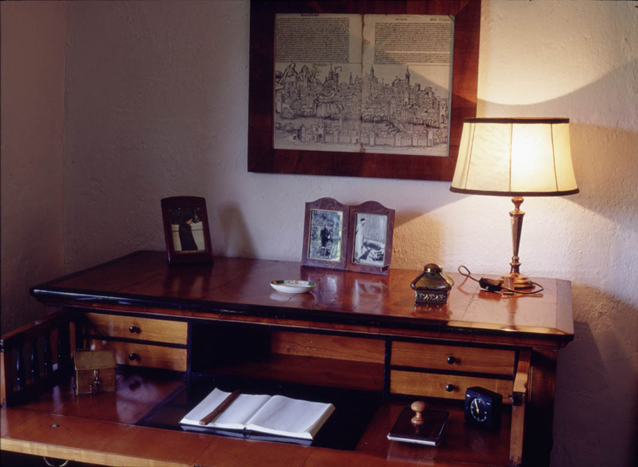

The second photo was actually of the desk itself, revealing the function hidden in the previous photo. On it sits a notepad and pen, a blotting pad, a clock, a handful of trinkets and three photos which appear to be of Bernhard himself.

On the wall there sits an old manuscript from Schedelsche Weltchronik by Schedel. The neatness, which I wager to be exactly in the character as it was when Bernhard lived and worked there and not enforced by its museum status, is perfectly logical, like the progression of a sonata form.

The kitchen is just as bare but it is beautifully so; renovated for absence in many regards, its huge size reduced to irony considering its singular occupant. Bernhard inverted the original principle of the building deliberately; the communities that thrived in such properties removed with a detached sense of purpose, leaving the lone man to sit within a physical embellishment of his own skull and the thoughts that whirled within it.

Photographs of outside the building are slightly more unusual. Most of them appear to have been taken in spring, the blossom still hanging on the trees. Yet, the building itself looks incredibly official, even daunting, rather than homely. In many regards, it is almost factory-like, designed for the making of the greatest amount of produce. It is fitting that Bernhard would be equally productive in the space while merely pottering about there.

There is, of course, no meaning to any of this. Bernhard wrote in a room in a house, and that is that. He created his memorial dungeons, empty spaces where his ideas lay cannibalising themselves until their form was finally pure. There is little else to express but perhaps I am being too much like one of his characters, too determined to let things lie when there are great currents still rumbling beneath the ordinary depths.

I come back once again to the man’s words, this time from his novel, Concrete (1982). ‘Everything is what it is,’ he wrote, ‘that’s all.’ There is no meaning, there is no reading. The rooms just are. And that is all.

One thought on “Memorial Dungeons: In Thomas Bernhard’s House”