Andy Warhol was far ahead of his time, in both the deathliness of his Polaroid portraits and in his use of the camera as a kitsch object. Other photographers found potential in similar Polaroid deathliness, but without such kitsch elements at play.

Walker Evans in particular found a new dimension added to his own style of portraiture when he used the Polaroid rather than his 35mm, the results differing a great deal to Warhol’s. Though not as effective as his photographs of non-human subjects, his images of people have a distinctive quality. He had no reservations regarding who he photographed, snapping whoever was close to hand, unlike Warhol’s motley crew of the Beautiful People.

Evans would take a number of Polaroids of the same people, capturing multiple stances and angles in one particular sitting. At one point, in capturing someone’s likeness, he usually moved to darkness. He desires the subject in their natural surroundings first, before framing just their heads in a stifling blackness, almost as if he’s taken them under a duvet and snapped their portrait up close. The result is unusual to say the least. At first it would be easy to read these photos as some suggestion of death, that the blackness will engulf every one of his subjects eventually. But it’s too simple a reading.

Instead, it’s better to see this in the context of Evans’ own life. His health is failing at the point he’s using a Polaroid Land Camera and he can see the end in sight. ‘The secret of photography is,’ Evans once said, ‘the camera takes on the character and personality of the handler.’ In these photos, perhaps uniquely, the blackness suggests more about the mortality of the photographer than the subject.

The most interesting portraits by Evans hint at this disintegration of the photographer’s body. The blackness of the backgrounds, the increased blurring of what can be seen, even in one case the total disintegration of everything around a particular subject; all say more about the photographer’s coming demise than the subject’s, as well as his loss of sight. The Polaroid that shows part of a woman in a world melting all around her resembles a visual embodiment of dementia. It’s a heartbreaking image and yet was likely caught entirely by chance, a fluke of the machine producing a greater, humbling insight.

Analogue machines are uniquely capable of creating such meaningful accidents. The strange colours break down into a liquid and, though we can still recognise and see the woman in question, the rest of the world is missing. She is without context, a fixed point in the midst of collapsing perception. Whether in blackness or distortion, the room is blurring and there is only the machine’s eye left to capture those last few moments of light.

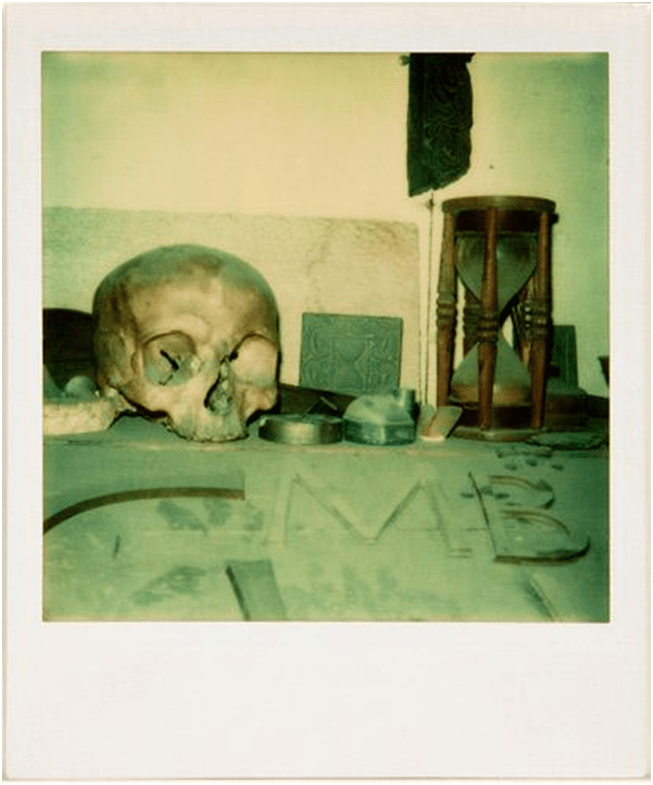

Earlier, I considered what a Polaroid akin to a painting in the Vanitas tradition could have looked like. It was no surprise to find Evans, in those final days, attempting to do just that, with an image that is the closest I have seen to a Polaroid’s Vanitas interpretation.

The image has the typical skull as well as an hourglass and the various objects that become mere paraphernalia when death is close at hand. The point in raising the existence of this photograph is that it does very little that is different to his portraits. They contain that same disregard for the world around as faces and people become all that matter. The objects on this desk become artefacts as all our possessions will become in time. Evans’ photo realises precisely what the philosopher Hannah Arendt meant when she said that death ‘not merely ends life, it also bestows upon it a silent completeness’. And in that silent completeness, only a few shattered fragments remain gathering dust.

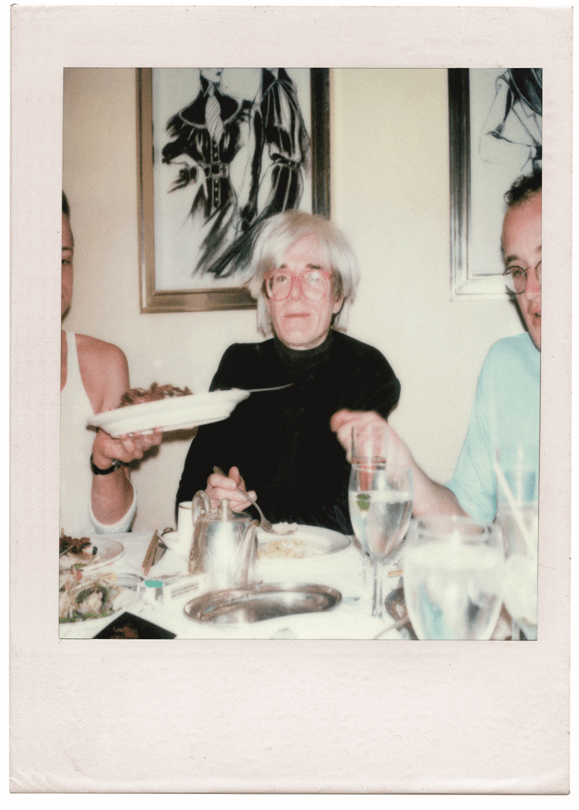

Evans was distinctly uninterested in celebrity, make his deathly visions different to Warhol’s. A better, more razzmatazz comparison to Warhol would be the photographer, Maripol. She not only photographed several of the same subjects as Warhol but did so for similar reasons, albeit with Andy’s quiet malice replaced with genuine awe.

Maripol has several labels often attributed to her. Vogue magazine called her the ‘Original Selfie Queen’. Hero Magazine call her the ‘Polaroid Queen’, while Document Journal call her the ‘Godmother of instant photography’. Her work is the beginning of the intersection between analogue deathliness and the media industry (whether it be celebrity, music or fashion in subject). For me, she represents a common thread between interesting uses of the medium and its more hollow, fragmented use today.

Maripol began taking Polaroids in the late 1970s. She hung around Studio 54 in New York and captured those who went in and out, a similar mob it must be said to Warhol’s Factory, including the artist himself. Maripol became heavily involved in the early 1980s music scene, in particular developing a creative relationship with Madonna. Glossy magazines still adore her work, usually because she documented the early formation of some of today’s style and fashion icons, re-humanising them in a warmer way than Warhol would have done. Her photos of Warhol especially feel like a friend’s casual snaps around a boozy lunch, which is likely why they’re so enjoyable to look at.

Her Polaroids often resemble those I’ve seen of friends’ parties. There’s a hedonism about them which feels carefree, no different from many photos of nights out except in regards to who is being photographed. Yet, in hindsight, they begin the process of hollowing out of the form, not because the photos themselves are bad but because their style is so easy to replicate; providing a method of attaining authenticity in the industry of make-believe. After decades of fashion shoots styled in a fake, grunge equivalent, Maripol’s Polaroids feel ghostly, as if they’re the last evidence of physical lived experience before we were forced, generation after generation, to fake it.

Her photos of Madonna especially are regularly published by magazines because they fit so perfectly into the current guise of ironic detachment. They possess minimal effort, at least on the face of it, and so look comfortable alongside the increasingly casual style of post-internet fashion shoots; often tricksy in their attempt to not look like they’ve tried.

A case in point is Julien Bernard’s series for The Ones to Watch, Girl’s on Film (2014). As the editorial excitedly suggests, the series is ‘inspired by the nostalgic imagery of the 70s and 80s’, the models ‘pull off messy tresses, bare-faced make-up looks’, and its vibe is ‘youthful, carefree and candid, much like the worlds one would associate with aged fashion imagery.’ They take the bare bones of Maripol’s era, eye and accidents, gut them, and replace them with products and bland, conformist beauty. Maripol’s images are a last gasp before we let these spectral simulations, like-Oh-My-God, take over.

If Polaroids create strange results when used in portraiture, it may be surprising to find the form popular in general image making, especially as an object of kitsch fascination. The camera occupies a twee position, just another aesthetic used by so many lifestyle bloggers, trendsetters, models and the less creative of fashion photographers. It has other effects but, to eyes so increasingly averse to the digital world such as mine, these images still ultimately seem morbid, cloying even, as if its physicality is being craved while everything else about them is subsumed by pixels.

Polaroids in these realms, especially when they pop up on the Instagram feeds of influencers, seems to offer some cathartic false redemption for lives hollowed by endless materialism. It feels like an attempt to re-authenticate what was lost when the choice was made to document and sell every aspect of the lived experience. They’ll never get back what they sold.

It will never not seem strange to photograph a plate of food, carefully arranged, perhaps with a product carefully placed behind. It will never not seem even stranger when such images are shot with a Polaroid camera. Having rifled and searched through an array of similar images taken on holidays and jaunts in the pre-digital era, such things were obviously subjects then, too. But the difference seems to be in the final effect. In those earlier Polaroids, there seems some desire to share their joy, a belief that once home, people (and certainly not strangers) may have wanted to see these things or that the photographers got some pleasure in revisiting them. The same level of trust is absent when seeing newly pristine Polaroids of suspiciously candid food, glossed bodies or luxury holiday views shared online.

Teju Cole has written of the increasing pitfalls in this dominant form of photography, many of which have unusual consequences when a Polaroid camera is used rather than the usual Smartphone camera and its subsequent filters. As he suggested, ‘the rise of social photography means that we are now seeing images all the time,’ later writing that, ‘the photographic function, which should properly be the domain of the eye and the mind, is being out-sourced to the camera and the algorithm.’ His criticism is precise and worth exploring further.

The result of this reliance upon instant share digital cameras, according to Cole, is one of subjecting reality to constant layers of illusion:

We are surrounded by just as many depictions of things as by things themselves. The consequences are numerous and complicated: more instantaneous pleasure, more information, and a more cosmopolitan experience of life for huge numbers of people but also constant exposure to illusion and an intimate knowledge of fakery.

This goes some way to explaining the retroactive popularity of the Polaroid camera. It’s not just second-hand nostalgia or simple curiosity, but an active solution to attaining that ever lucrative authenticity. It’s not the death of people that the modern use of Polaroids speaks of, but the death of any meaningful reality.

Even modern celebrities cannot resist an attempt to authenticate their lives for the general public. The results are the most deathly images imaginable. This is the future Warhol saw, though to my eyes the Polaroids that litter glossy magazines and websites like Instagram also have disturbing parallels to Jeffrey Dahmer’s images.

There’s a range of things happening when Polaroids enter these spaces, most of them unintentionally bizarre, though sometimes heartening on a rare occasion. The point to make is that the Polaroid works in relation to the human body and not always with the best of intentions. The skin may be smoother, whole contours of face and body more blindingly reflective, but the result when seen in a Polaroid is one that is decidedly not what I think their intention was.

The Polaroid is nothing new in these industries, of course, and its modern use as an ironic attempt to regain some lost authenticity does result in the all-important clicks. All models in particular will have “Polaroids” of themselves as part of their work. The word does not denote actual Polaroids anymore (though obviously once did). Instead it refers to a very basic image of a model, often without editing and with limited mediation so that art directors, casting directors, stylists and photographers can see if a particular face can work with an idea. The idea of a Polaroid denoting a stripped down version of a human persona is a deeply Warholian ideal to say the least.

Model Polaroids were quick, cheap and easier to share before the digital age rendered them inconsequential. As with everything in this new hyperactive period, the industry has bastardised the real. Polaroids now are some of the strangest photographic objects around. Firstly, such “Polaroids” are shot on digital and look as you’d expect; a pared down digital image. But even stranger is what many model management companies do to them. As if attempting to bring the real back into their world of fakery, many model “Polaroids” stick a real Polaroid frame around the digital images. The result is absurd.

Digital photographs, when framed with a Polaroid boarder, crinkly and white, gives rise to a feeling akin to watching colourised films originally made in black & white. Something is off. Something is wrong. There’s no reason for this to happen and yet they go through the motions; this is authentic, the model’s beauty is as real as this image. This can be held, admired and positioned in real life, just like the model in the image can, for a price.

Honest.

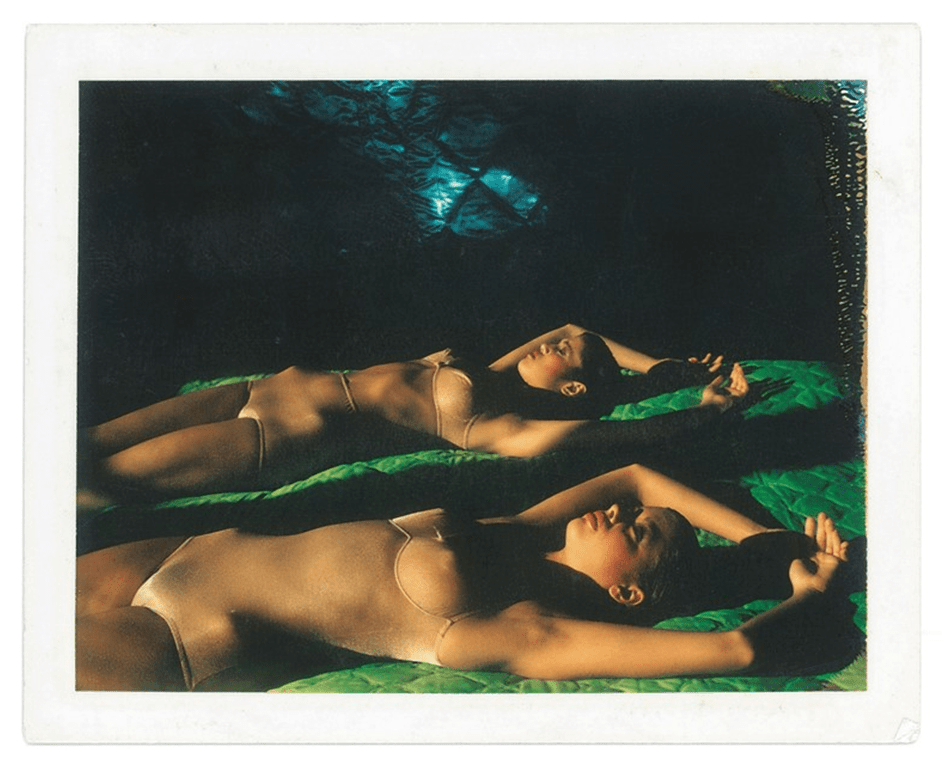

Real Polaroids in this realm don’t fare much better, often because they’re taken of heavily edited scenarios while at the same time battle their natural, candid appearance. When looking at the photographs of the artist Guy Bourdin, for example, his use of the body – even one from the prime era of Polaroid’s domination of public imagery – produces a result unusually similar to today’s images.

Take his 1978 Polaroid of two models lying in the most unnatural of positions. The colours are rich and the photograph exudes heat but the bodies look decidedly left in the sun. Rather like in Agatha Christie’s novel Evil Under the Sun, a body left in a pose seen in the brightest of sunlight can deceive, and there’s a feeling in Bourdin’s photo of a similar deception. Everything feels false, the body language feels reactive to a gaze. Everything is facsimile. It looks more akin to an advert because that is what it primarily is. It’s telling that Bourdin would soon turn to disappearances, creating illusions of invisible bodies.

Fashion imagery has the Polaroid in its arsenal of stylistics, often insinuating some retroactive aesthetic to match a particular mode or style of clothing coming back. They use the set-up akin to an image like Bourdin’s but claim it to be a potential reality. Unlike in Bourdin’s photographs, which clearly had the germ of excitement about using the most modern and unusual of machines to experiment with, the modern use of the Polaroid in such imagery becomes more and more unusual as it is examined.

I find myself paused momentarily in my browsing of such photos, scrolling through bland, perfected images on Instagram of beautiful people. Just like the awkward, grating contrast between the digital photos and the real Polaroid frames of model agency calling cards, the use of Polaroids in these hyper-stylised, utopian images of influencers is strange and unintentionally deathly. Their desire for a real-world present (“This is happening now!”) falls flat, and the contrast between an aesthetic of the past and their luxurious desire for today hints towards the morbid. We are asked to look at Dorian Gray’s perfect image, all the while knowing what’s underneath, and expected to buy it.

There’s no escaping the bad fit between those edited bodies in a theatre of luxury and the everyday Polaroid format. They perform the action that Warhol enacted on his celebrities quite voluntarily and unknowingly. In between the complex shoots in exotic or lavish locations, sits the odd Polaroid. There’s a reason for this. In a world dominated by the imagery of Instagram, a perceived sense of the real is key. You can live this, if you pay the price. And if you can’t? Well, at least you can see it.

Like when Dalgliesh insisted on Polaroids of crime scenes, there’s clearly a greater trust in something that was there in the moment, explaining why so many users opt to use filters on their photos to give the same hue and colour saturation as a Polaroid; as if it’s more of a real photo when within this aesthetic. Trust is an integral part to the illusion of the lives that keep websites like Instagram going. It also explains why so many people download apps that turn digital photos into fake Polaroids. Those edited digital photos never existed, their information ages only in the context of the wider digital world which is an endless stasis. A filter cannot provide humanity or history at a click.

I sometimes wonder whether I share some things in common with these beautiful people, for we seem to both be searching for some temporary redemption for what we want to photograph. I want to retain the memory in more than just an image of my journeys and strange pilgrimages. Perhaps they want to do the same, albeit what they want to retain is their sense of body image in that moment. They use it for more cynical ends, for likes, shares and sales, but in the years to come when their main commodity will have aged below any meaningful value in that brutal realm, those Polaroids will likely mean more to them than the thousands of degraded, pixelated photos stored on unseen hard-drives.

Not all such figures online use the Polaroid in this way. Others use its presence for their own particular ends. The millennium has increasingly witnessed another gradual death as the years have gone by: the death of privacy.

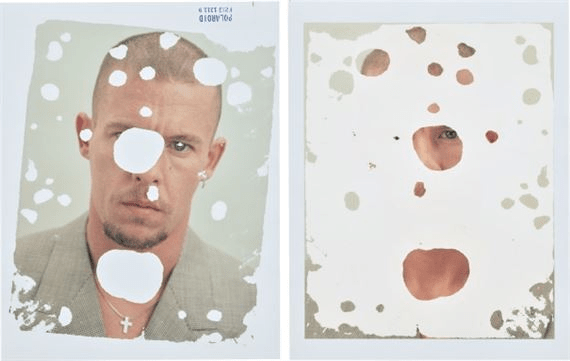

I think often of a series of failed Polaroids of fashion designer Alexander McQueen. McQueen was a working-class genius, chewed up by the industry until his suicide at a depressingly young age. A few years before his death, photographer Steven Klein took a series of failed Polaroids whose accidental distortions seemed to capture the increasingly fragmented persona of the subject; a man hounded by the press for his controversies, hounded by the industry to continue a relentless working pace, hounded by himself and his demons of drug addiction and childhood trauma.

The photos were taken in 2002 when McQueen was beginning to go into a death spiral. He’d had liposuction to drain the fat from his body, his new image of trendy clothing and tucked chin arguably signalled the beginning of the end; the designer taking his own life in 2011. But the Polaroid seems to symbolically capture McQueen’s world in that moment; its distortions accidently revealing the private chaos of the man’s difficult life.

The Polaroid is the perfect combatant of false authenticity, not least because its imagery has the potential to not be shared at all, or to be seen only in a shadow existence online. I only saw those images of McQueen, for example, because they were being auctioned online.

It exists but it does not need to be viewed completely to be recognised. Even more uniquely it can witness scenarios, it can watch the passing of time and be unearthed decades later. It resists virtually every accelerant coined in the twenty-first century, and it is perhaps for this reason why some of the most famous people in the world look to it as a device to regain some of their lost privacy and sense of self. They may share its images but they will always be mere scans. The original will have the charge that they can retain for themselves away from the greedy, prying eyes of the public.

The power that presence gives to Polaroid photography finds itself harnessed in the most unusual of places. Certainly, the most unusual to date that I’ve found concerns the social media of the performer and activist Emma Watson.

One of the most famous women in the world, Watson is also one of the most photographed, both officially for magazines and launches, and unofficially by roaming paparazzi. She is also arguably one of the most famous users of Polaroids, though if asked what she was famous for I doubt this would be high on the list. I find this contrast fascinating and not totally disconnected: that someone so photographed finds something of merit within a Polaroid. It feels a very natural and quiet rebellion.

With arguably more photos existing in some form or other of her in the public domain than most other women, the Polaroid itself provides an unusual sense of escape and recollection for the celebrity, though no doubt could be applied to many other figures of such status if they decided to start marking their public life by the tiny, white-framed images. Watson seems to have found the opposite aspects that Warhol found in his Polaroids in spite of arguably occupying the same realm.

Watson began posting Polaroid photographs on her Instagram feed in 2018. These often consisted of her casually posed, but also highlighted many of the issues she publicly raised regarding gender equality in particular. The photographs range from candid portraits to more official looking photographs for the high profile events she attends. A question generally could be asked: Why Polaroids? And an answer in the equally general sense could be something mundane; perhaps a lucrative promotion, a free camera and stock sent from Polaroid themselves, now seen by Watson’s millions of followers on the platform. But the results are too unusual to shrug off as a mere promotional coup for Polaroid as a company.

The form has another intriguing function for Watson. Through seeing objects held by the celebrity and within a personal space far removed from studios, press junkets and the street harassments of celebrity pap photographs, it provides an authenticity of image (of her image) that most photographs simply cannot possess. It’s more personal, more relatable, more there. Most importantly, it manages to achieve this even when scanned and shared within the digital realm. They still manage to somehow feel within her possession in spite of being sharing.

The moment with her is shared only in essence and retained in the physical. A sense of true self is guarded and retained. While other figures online use Polaroids to provide a false authenticity to their lives and the lifestyle they are selling, Watson seems to find something less cynical in using the camera.

When Watson takes a Polaroid of herself, or more likely has one taken for her, she is sharing this with the public but the moment is still hers. Her Polaroids are more charged than the numerous mounds of press photographs because such digital photographs can often only go one of two ways. The first is that there was professional consent in which a sense of public performance is more palpable, and also inevitably disposable. This was the sort of façade that Warhol took pleasure in murdering with his own Polaroids. On the other, her many digital photos are undermined by the creepy stealth of paparazzi photography. They are almost always non-consensual and, for a star of Watson’s status, so ubiquitous and aggressive that they constitute a form of hostile surveillance that is almost impossible to comprehend existing under while staying sane.

The Polaroid was there. It was held by her. It existed physically in a world that was solely hers and the photographer’s. It was not held within the digital camera of a high-level photographer at Vogue; it was not even held on her personal phone or the phone of friends. It was there, affected instantly by the weather of the space it was taken, perhaps stuffed into a bag or pocket until back at some place where it could be scanned. It travelled with her.

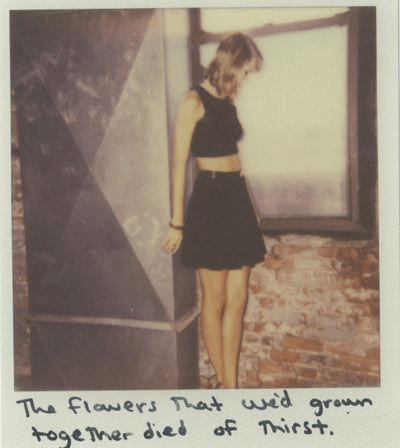

This may sound banal, but such personal intimacy is often prized by those who follow celebrities, and the subsequent invasion of it is lucrative for press photographers. The Polaroid feels more powerful than all other photographs in this sense. This power can be, and is, bastardised by the same industries. Taylor Swift, for example, faked the intimacy entailed in such photos as a guise to sell her records, writing airy, inspirational quotes and lyrics from her songs in pen upon their frames in the run-up to an album release. It feels totally redundant in real terms but undoubtedly created a false intimacy with her fans that other photographic forms would have struggled to replicate.

There’s a conscious sense that Watson is more aware of how to use it effectively. This is exemplified by an unusual montage of photographs put together to celebrate a particular political event she attended, advising on the Gender Equality panel at the 2019 G7 meeting in Paris. The meeting was high-profile, filled with politicians, celebrities, activists and the like. For such an event, the most obvious photographic form to document it was digital. Search for the event online and almost uniquely digital photographs come up. Plenty exist of Watson but the most interesting thing was what she did on her own social media.

Alongside a handful of real Polaroids, the digital photos of the event were put into Polaroid frames and edited into a huge image that took up several of the tiled spaces on Instagram’s tessellated page. Each tile showed part of the larger collage, from the official press photographs and meetings with French President Emmanuel Macron, to a few real Polaroids of the Eiffel Tower and photos from within the meeting. The fact that Polaroid boarders were applied to the digital photos could be read as simply desiring continuity between the handful of real Polaroids and the digital photos. But to me it seems that the continuity desired between the two different forms isn’t an aesthetic one but one of presence.

Those casual Polaroids feel so much closer behind-the-scenes of the important event and, even though the digital ones had equal access, they feel more mediated, less there. The boarder provides a handy sign that they were just as real and present, even if similar to those taken by press photographers who ultimately failed to get further than their side of the red rope.

This turn to Polaroids for Watson came around the same time she shared the work of the rediscovered American photographer, Francesca Woodman. The final point to make is in connection to Woodman whose photographs often explore women’s bodies as they become entangled and part of their surroundings, to the point of fading like spectres.

Watson’s use of Polaroids comes around the same time she shared Woodman’s photo of a woman becoming part of the wallpaper, and there’s a strange relationship between them. Like Woodman’s women, Watson seems to be venturing back into the ordinary. For someone so famous, this is an affirmative act rather than a negative one, as if the use of Polaroids will remove her sheen of stardom, just like Warhol’s Polaroids did. It becomes a positive action, and the removal of her glamorous, reified self actually moves her closer to normal life, back to being human rather than a projected ideal.

Whereas there was melancholy within Woodman’s stunning 35mm images, Watson’s act of dissolving back into ordinary life – as far as is possible for someone who has been in the public eye since early childhood – seems a free and affirmative act. For a woman with over seventy-three million followers on Instagram alone, the act of disappearing back into the ordinary must feel like a release, a new freedom from the digital body and an escape from what David Bowie sung about in Fashion.

She escapes the Goon Squad.

The man whose death hurt me so in 2016, and whose Polaroids became a sort of solace, provides the answer to what the Polaroid can truly be: escape ‘It’s big and it’s bland, full of tension and fear’, he sung. Perhaps that’s what Watson briefly leaves behind when within an analogue grain; not watched by thousands of eyes, but just a single pair through the lens of a Polaroid camera, one whose real product only a few people, perhaps only those who truly matter to her, will ever properly see.

Memorial to the Moment

The most beautiful view in the world is of a graveyard. I can’t remember the first time I saw this view but it has never left my mind’s eye since. I often think of it in times of need or remembrance; that there is something still peaceful out there among the noise.

Cley-Next-The-Sea is a small village on the north Norfolk coast. It has become quite a popular destination with tourists in the last few decades, not least for the views of its famous windmill over the marshes, its small but lavish array of shops and its proximity to the vast reed-beds and coast gifting it with a wealth of birds and wildlife. This latter reason is partly why I came to know of its endless skies and yellowing hues, due to my father in particular whose obsessive passion for birds resulted in many a trip to the area.

This view that I think of often isn’t actually of Cley itself but is instead seen from Cley, looking out over the marshes at the time of day when the sun is threatening to sink. Being somewhere so famously flat, dusk in Norfolk is often an overwhelming occasion at the right time of year. Rising in the distance above the vegetation is the church spire of St. Mary the Virgin at the nearby town of Wiveton. It seems to grow out of the land like a natural beacon, just as its design undoubtedly intended when it first stood in solitary vigilance over the wild wetlands of the coast.

At a certain point, the church warden lights the many candles in the building and the vision of this light shining from its window is truly beyond words. When the sky has turned that blue-grey tone that only those who have seen Norfolk in autumn will fully understand, its warm glow sets the whole marsh alight. Every time I have witnessed this beam shining down on the graves and nearby marsh, I have felt akin to floating.

My memories of this place are fond, rendered into segments by the grammar of a barn owl’s appearance haunting the plains. The vantage point for this view is taken on the sloping stone steps of St. Margaret of Antioch, the imposing neighbour of the Three Swallows public house whose murmuring pleasantries and clinking glasses can be heard lightly on the breeze as the locals descend to share a few short hours gazing into the embers of a log fire. It is a vision of calm that feels almost alien to experiences of every other place I can think of, as if the porous nature of its land drinks all anxieties away. If I wanted to capture a moment that could be returned to at any given time, it would be this one.

I revisited the location recently armed with my Polaroid camera during one of the many crises that seem to constantly define our era, almost for the feeling of coming up for air. There was no window beckoning me to jump from but the horrible numbing distance was there all the same.

Uncertainty plagued me, not least because it had been so long since I had come to Norfolk. I feared that the violence of a Polaroid’s flash would chase away the pleasing ghosts of the marsh’s atmosphere. After a drink in the Three Swallows, with its crackling fire and gentle conversations, the autumnal sun sank behind the horizon, turning the reed-beds black in contrast. It was the right time. I wandered out alone to the church next door, its long steps the perfect vantage point for the most beautiful view in the world. For a moment, I swear I could even hear the rumbling call of a nightjar. The church warden had already lit the candles in St. Mary’s over the way, its light translating the colours of its beautiful stained-glass window over the gravestones and beyond.

My memories rumbled on, of happier times when family life still existed properly and a sense of home still remained. I aimed my Polaroid from a few different angles, realising ultimately that no machine could capture this image truly as I saw or remembered it. At the least, however, the Polaroid could capture that moment, in witness to the view that for me towers above all others.

The Polaroids sat around developing as I stared further over the marshes, daring the barn owl to show. When I look back on this view, and these Polaroids attempting and failing to capture it, I think more than anything else of mortality because, if I was lucky enough to have a say in my final view of the world, it would be this one; reliving those memories of happy family times as nightjars hummed from afar.

The Dutch philosopher Spinoza once suggested that consideration of death was often a characteristic reserved for those who were not free. ‘A free man thinks of death least of all things,’ he wrote, ‘and his wisdom is a meditation not of death but of life.’ In his terms, I am not free. Nothing preoccupies me more than consideration of my own demise, in particular the unfortunate comfort it brings when it seems a pleasing alternative to whatever frustrations are spinning around my skull at any given moment. My perception is broken, outdated even, just like the lens of Polaroid, which is why I find such kinship in the imperfect machine.

I often worry that my obsessive learning of recent years, a compensation for a poor education early on, hasn’t really been learning at all but instead a constant practicing of the concealment of stupidity which I still in all honestly believe lies as a weakness at the centre of my thinking, writing and everything else. The only antidote to this concern has been, in my experience, to constantly ponder innocuous things like Polaroids; analogue artefacts that embrace the imperfections that exist in us all. Such things help avoid these reflections for a time.

Then I consider the Polaroid at Wiveton and, in spite of its calm, I know I am not ready yet for its beautiful view to be a full stop. There are more Polaroids to be taken, more distractions to be had, more curiosities to follow. But this Polaroid is mine, and mine alone.

I cannot share it.

I wonder sometimes if I will have a grave when that last moment has passed, but then I look at the piles of Polaroids from my walks and consider that I have already accumulated a great many graves to the dying moments of my life. Those little graves have brought moments of joy, even when their subject has not been the view out towards Wiveton as the sky caught alight.

I hope that if I am afforded some marker of my absence once gone, it is not littered with the odd pile of soggy flowers. Instead I hope it is marked with endless Polaroids, the stone or tree smothered in the little graves of others; fragments of their lives given to mark what I hope is a humble future absence.

A memorial to the moment lying gently like a veil over our memories: that is what a Polaroid truly is.

An end.

One thought on “Presence, or Polaroid Ghosts (Part 17)”