We are the Goon Squad and we’re coming to town

When David Bowie died in 2016, it felt for a moment like someone had removed a piece of my spine. The feeling was a mixture of frustration, at having only fully appreciated the musician’s work later in life, and worry, at having relied on his work to get me through my own on a daily basis.

And then he was gone.

It happens.

His music remained but it was now finite and archival. If the singer was an epoch, then that epoch was over and I had only just cottoned on as to having lived through it. Bowie’s music couldn’t be finite, could it? When the playwright Harold Pinter died, the actor Michael Gambon said that the ‘rod’ from British theatre had gone and that, in having left, ‘we were all weaker for it.’ It was the same feeling for Bowie’s death, many flooded with a sense of not being quite sure what to feel, what a cultural landscape without him would really look like.

Like certain other cultural institutions, Bowie had, for my lifetime at least, always been there, and the thought of him not being there was unbearable. All of his music became newly morbid and melancholy, so affirmative in being alive that it seemed subsumed in the hindsight of his death, not helped by the fact that his final album, Blackstar, had been specifically recorded with this hindsight firmly in mind.

This new Bowie-less epoch was awful, and the world seemed determined to reflect this awfulness with regular consistency from henceforth; still continuing to this day in the constant barrage of inescapable news cycles and catastrophes. Perhaps it was really the end of the long twentieth century; similar to the stories of Victorians still pottering around in the 1920s as modernity rose up and they wandered around with a look of befuddlment at world as it changed and left them behind.

With his music not helping or providing any sort of solace on the day he died, I looked to the endless array of photos of the singer online, his chameleon-like ability to morph ahead of trends and time still awe-inspiring. But those photos, too, were filled with a grating contrast. They seemed more alive than the actual singer was.

Bowie was endlessly photogenic and it was absolutely right that later he would end up on screen starring in films as much as making music. Album covers, so ingrained into the West’s cultural psyche, became posterised into posthumous relics from a time groaning under the weight of a collective nostalgia, still growing heavier as the years go by. None of it was helping as 2016 fell into its ongoing shadow. That is until I found a photo of Bowie that I felt matched the new reality of his absence.

Of course, it was a Polaroid.

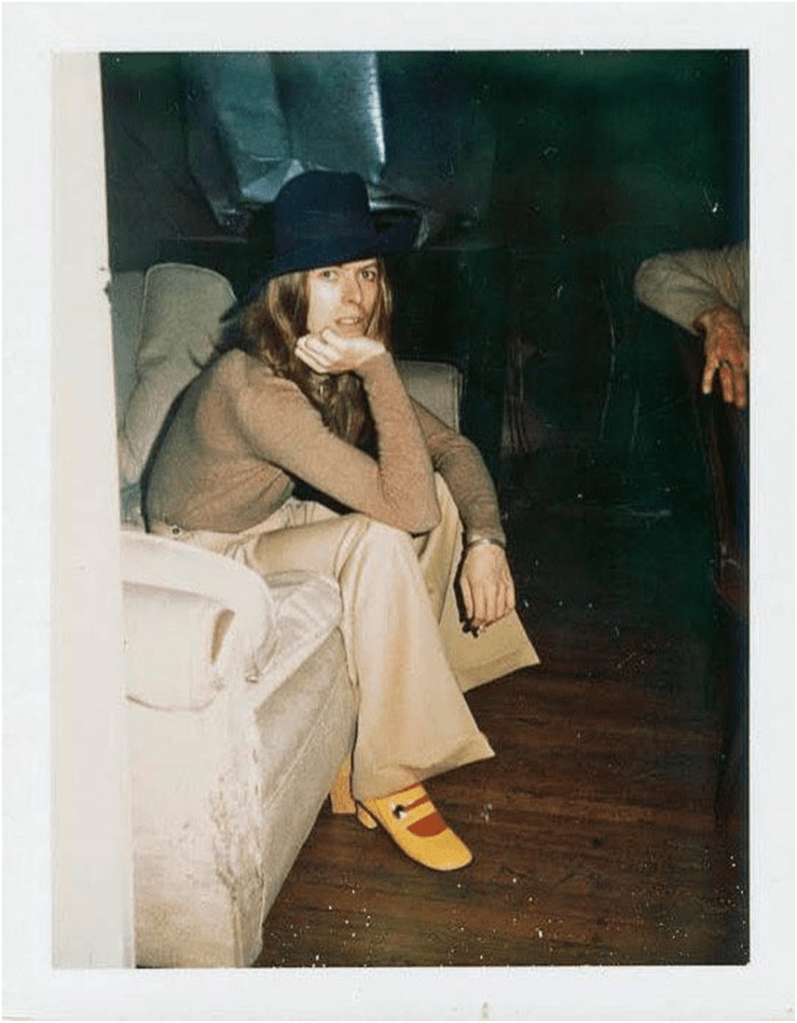

The Polaroid shows Bowie in 1971. He’s wearing an outfit that’s so incredibly David Bowie that someone else wearing it would be seen as trying to become the singer for fancy dress. He’s wearing a large blue hat, a range of 1970s beige clothing with an outrageous combination of heeled yellow shoes and red socks. He could be a character from a strange adaptation of an Agatha Christie novel, part-eccentric dandy, part-reluctant aristocrat.

Another less famous Polaroid actually reveals only one of his socks to be red, the other being navy blue. Bowie and odd socks are a fitting match. The Polaroid, along with others from the same session, was shot during the filming of a strange video piece, the large blow-up objects of which can be seen in the background used like strangely demented weather balloons as the singer wandered dreamily between them.

I hadn’t really thought much of the performance when seeing pieces of it some years later on grainy VHS footage. The Polaroid was far superior in actually capturing the singer’s character as well as more confidently existing within his present absence than any abstract video piece could. The performance itself was conducted by the photographer of this Polaroid, Andy Warhol. I didn’t know this at the time of first seeing the image though certainly knew of the connection between the two men.

Andy Warhol looks a scream

Hang him on my wall

Andy Warhol, Silver Screen

Can’t tell them apart at all

The reason why the Polaroid was so comforting for me I think lies in its overt deathliness; not in its subject but in its aesthetic. The colour palette, the texture of the grain, the photo in its context of a frame, all hints towards memorialisation. There was no friction between the old image and the new reality. No matter how bright Bowie’s odd socks and large hat, Warhol’s image is more comfortably one of a dead man from the past.

Polaroids are death caught in amber, the moment memorialised and marked with an analogue grave. This is partly why I find casual Polaroids so interesting and occasionally darkly humorous. They unconsciously murder everyone within them. The happy, more jovial and inane of photos (especially modern Polaroids rendered hipsterish in their co-option into lifestyle, fashion and marketing material) look especially ridiculous.

In comparison to the many images I’d seen of Bowie, this Polaroid was far closer to a memorial and was more comforting because of that. It confirmed his absence in a more accepting, understanding way, in many ways displacing it from the present; tricking myself into an early acceptance of losing someone whose work I greatly admired. I soon looked for more Polaroids of the singer, eager to bolster the feeling. The more I found, the more they dammed up the awful feelings.

There were more ragtag Polaroid images of Bowie backstage before and after gigs, sometimes in full make-up, other times so blurred as to resemble an impressionist painter’s interpretation of the singer. I loved the humanness of these images, confirming again for me that the Polaroid’s true genius lies in the fact that photos taken by non-professional photographers are often just as (if not more) interesting. They feel like shaky, excited fragments of perception, their photographic weaknesses becoming evidence of human joy.

Other Polaroids showed Bowie filming or recording, whether in music videos or film roles. Some were behind-the-scenes shots from the filming of Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), which looked decidedly odd; the natural futurisms of the science-fiction film thrown back into the aesthetic of the decade of its production. Perhaps the 1970s really were the future we were all destined to live in.

These images weren’t quite the same as the Warhol Polaroid as they seemed outside of the moment; the moment that would eventually play out on screen through the frames of the film. Bowie also looks even more alien because of his role as an actual alien in the film, the flash turning his white skin blindingly pale, to the point where, in one particular shot, he blends in with the surrounding white sand of the film’s location and vanishes. Only his eyes remain, surveying the set like a mischievous Cheshire Cat. If Bowie was already some kind of alien phenomena, the Polaroid only added to his extraterrestrial intrigue.

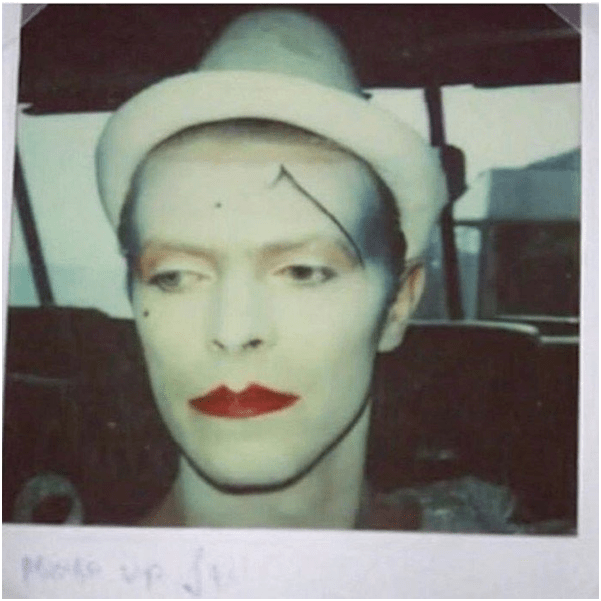

One Polaroid in particular felt deeply melancholy, a make-up continuity image from when Bowie was filming the video for his single, Ashes to Ashes, famously dressed as a sad clown looking on with dismay at the world, wondering whether he’s the imagined soul of a man in a padded cell or a mad man in the daydream of a lonely clown. The video is apt for this discussion as Bowie is seen having his photo taken in the video with a large analogue camera by a clichéd paparazzi photographer on a strangely alien beach, coiling over in pain as if the photographer has taken something from him or injured him. What did the photograph do to injure the clown? Either way, he seems in character and, more importantly, memorialised. Again, this is the image of a man who isn’t there anymore, his white make-up helping the Polaroid’s flash render the singer’s skin soft and ghostly.

It was Andy Warhol’s Polaroid that helped me most that day, however, and it was perhaps the first and only time I have really connected with the artist’s work, that is outside of his other Polaroids. Beyond this medium, Warhol has generally left me as cold as Bowie looks in his Ashes to Ashes Polaroid. The artist’s work has uniquely failed to suggest little to me other than the formation of the art market.

Warhol’s mixture of celebrity, commercialism and irony captures a very particular aspect of cultural society today; an audience distanced enough from any particular social relation or problem who can happily play along with the gag but daren’t ever suggest it as being one. The whole illusion would otherwise come tumbling down. Better to keep it going rather than be ostracised for philistinism, a natural reaction when considering Warhol’s largely ordinary work.

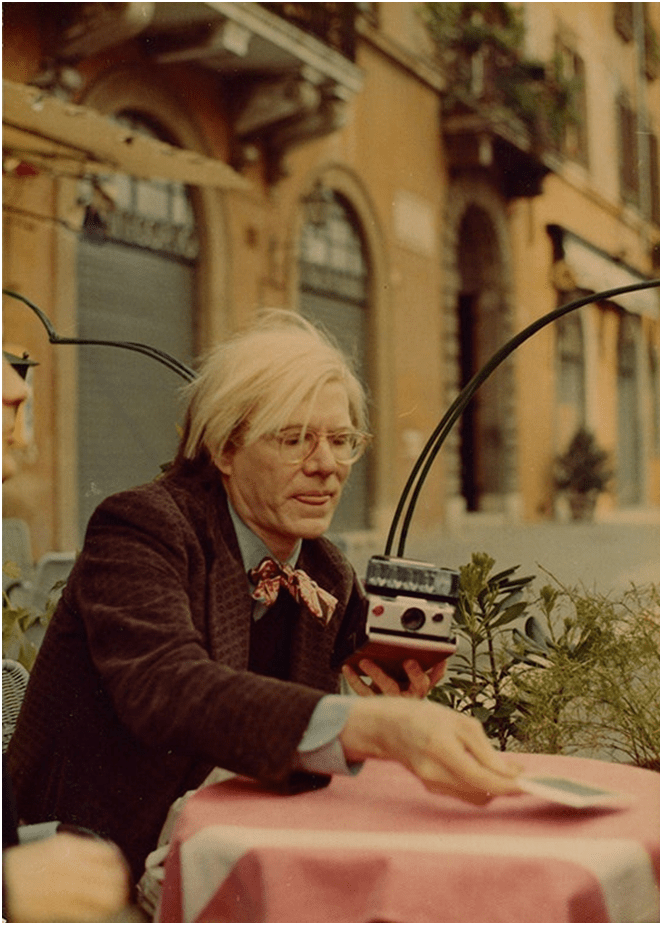

The artist embodied what Frankfurt philosopher Theodor Adorno labelled as The Culture Industry. The so called ‘triumph’ of advertising was that the consumers could see through the machinations making them buy into the products but still did so anyway. Warhol’s work is no different though his Polaroids feel somewhat distanced from this idea, more legitimate than Warhol’s other forms of media and yet distinctly within his own interests. They are his ultimate contradiction.

‘You have to treat nothing as if it were something’, Warhol once said. ‘Make something out of nothing.’ His mastery was in selling these objects as extraordinary artefacts, an act that itself was certainly skilful and intelligent. It’s easy to see how his philosophy found traction in the Polaroid photograph: an object that defies its own ordinariness as we have seen throughout this book, while still ultimately cloaked in its workman-like approach to creating images. There are contradictions within this, too.

Each Polaroid is arguably unique, not just as an image but as an object that lives a far more tangible, physical life compared to most other photographs. I think this contradiction also explains why Warhol liked the machine; the ambiguity of its product was yet another dare to critics to write off the object due to its ease yet undeniable in its power as an object. On the one hand, it was a mass product, and on the other, each photo was utterly unique.

Jean Baudrillard wrote that Warhol’s work was essentially ‘promotional’, calling the artist ‘a trickster who has absorbed the drollery of the commodity and its mise-en-scène.’ His ability to blend advertising and new technologies was undoubtedly accomplished, the most accomplished to have graced the art world, but also the chief reason why he still finds so much purchase in today’s climate of surface obsessed cultural criticism. Warhol is the perfect artist to embody the hollow present. He is rightly celebrated for being ahead of the curve before so many others were subsumed by this philosophy, where a Warhol approach of nonchalance to everything is now normal.

Warhol’s Polaroids are the one aspect of his work that straddle the line between the genuine and the fake, and the specific use he found for them was undeniably fascinating, especially in their relationship to death. I think he cared about them more than any of his more famous works.

I find Warhol’s Polaroids fascinating and eerie. The camera in some ways found its perfect match in the artist as its guise of mass commercialism and ability to render even the most exciting of situations as merely normal (and vice-versa) connected to some of Warhol’s ideas.

‘The best thing about a picture is that it never changes even when the people in it do’, he once quipped and this gets to the heart of why, in his typically malicious way, Warhol’s Polaroids are interesting. They clearly had some personal use, almost beginning the process of violently re-humanising the most detached and beyond-human of people: celebrities. The Polaroid is weaponised against his subjects in a number of ways, just as Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes clown grimaces in the video as his image is stolen in a flash.

Aside from his Polaroids of Hopper and Bowie, Warhol took to photographing everyone who was milling around his usual New York haunts, creating a Who’s Who catalogue of the time. In these photos, he took the most famous people of the era aside, found a white wall and stuck them in front of it, rather like a cop getting a mug-shot. Rarely does it seem that the artist treated them particularly better than a policeman treats a suspect.

Even on a historical level, the photographs are interesting as a time-capsule of the era’s creative scene, its evolution and its eventual disbanding. The clothes worn in these photographs are minimal, the looks on their faces blank and devoid of emotion. They could be contortioned corpses or wax works stolen from a museum, such is their emptiness. In terms of portraits, they are the photographic equivalent of a glass of water. There is little humanity on show and it seems Warhol saw these bodies as just another mass product in his catalogue.

The result when seen on mass is something akin to viewing a taxidermy collection, or perhaps a strange, showbiz morgue filled with the bodies of the previous era’s famous faces. This clinical character is surprisingly unnerving; especially knowing just how many of the people in the photos would actually die not long after Warhol had taken their image and usually well before old age.

Warhol uses a very particular aspect of the Polaroid – its ability to strip away almost all of the basic layers of a human face or persona – and turns it upon people who have the most in-depth and complex web of personas created for their own work. In other words, the projection of a persona that celebrities, especially musicians, rely upon is removed. Who else has more to strip away than the rock star or on-trend contemporary artist? In Warhol’s hands – and I think he was acutely aware of this – the Polaroid camera became a murder weapon of sorts; killing the illusions cultivated over the years.

All is stripped away. They’re still just people.

Susan Sontag suggested that Warhol’s work defined itself ‘in relation to the twin poles of boringness and freakishness’ with the strength of ‘self-protective blandness’. Perhaps the bland reality of these people behind the facade was what Warhol was ultimately in search of. It’s easy to see why the Polaroid as an object can fit into this thinking, being both everyday and unique; protected from analysis by its own particular ordinariness. It’s also why Warhol clearly loved it, becoming a singular factory that produced images almost as a mechanical process. To paraphrase his friend William Boroughs, the Polaroid turned Warhol into the ulimate soft machine.

With the whole process of photography (at least before the digital revolution) self-contained in any person who held and used a Polaroid camera, it’s unsurprising to find Warhol smitten with the machine. But there’s a darker side to these often celebrated images, in both the histories of the people within them and the reality of what killing their image achieved in photographic terms. The artist merely collected future corpses.

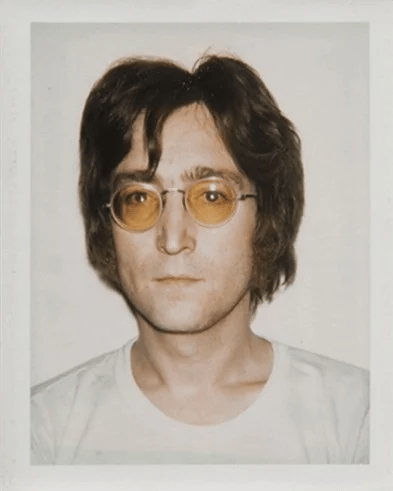

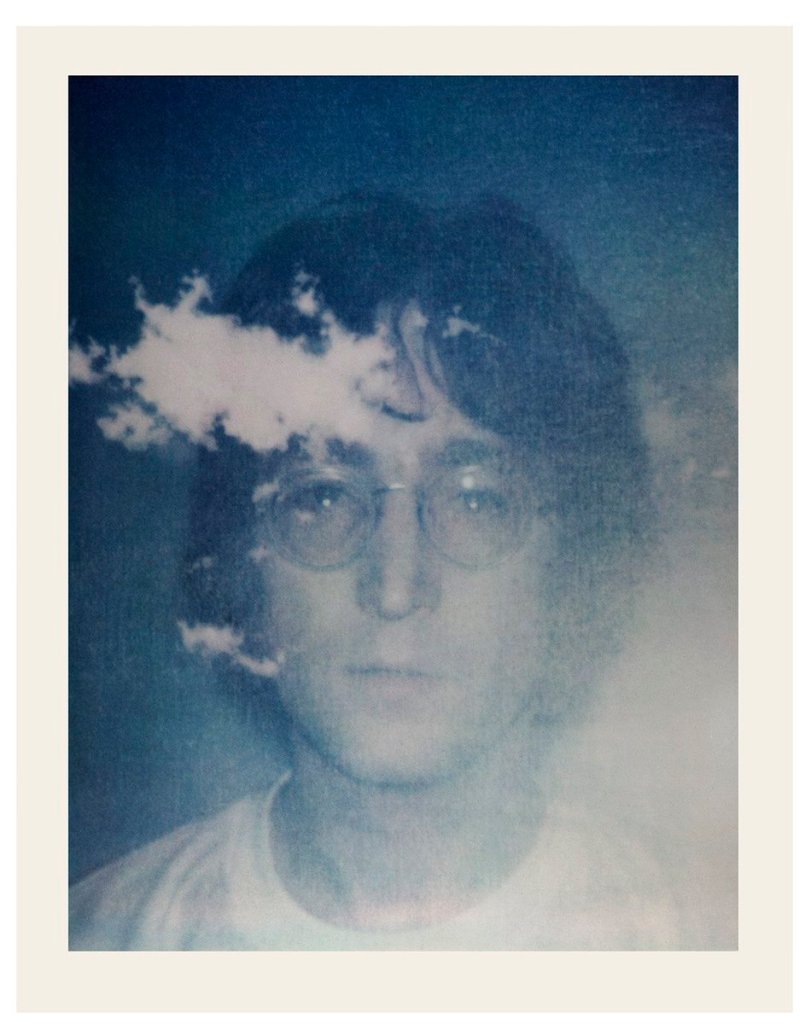

His image of John Lennon is particularly intriguing. It resembles the cover for Lennon’s Imagine album from 1971, the image only differing from its superimposing of another Polaroid of a cloud over Lennon’s face, as if he’s looking down from on high or his spirit is actually in the process of leaving his body.

The Polaroid of the cover is attributed to Yoko Ono though the likeness, even down to the clothing and angle of the camera, is uncanny and there is much speculation as to whether the original image was in fact taken by Warhol himself before it became superimposed over the other. Or perhaps Warhol handed Yoko the camera to take the shots in question. If the original image was by Ono then it does beg the question of what Warhol’s aims were aside from adding to his collection of celebrity taxidermy while mocking Lennon’s promotional image.

The whole styling of the original photo looks like an abstract version of the afterlife rendered in a minimalist stage-play. Lennon’s look is haunted to say the least. The light of the flash strips away any last pretence still held from his time in The Beatles, all of its gimmicks, fads and She Loves You’s reduced to a look devoid of any real life. He seems hollowed to the point of non-existence. This to me appears to be Warhol’s purpose in his Polaroids at least. Even if the body is still living and making work, his intervention is a murderous one, killing the celebrity with omen-esque precision. It’s not as if the artist himself would be immune to his own weapons; the Polaroid camera has a half-life that eventually degrades the user as well as the subject.

Still, Warhol enacted this murder on virtually everyone around him, in particular his fellow artists. There are a range of Polaroids existing of the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Mapplethorpe, Keith Haring and more. All have the same quality: resembling a continuity Polaroid from a film with minimal distraction from the person themselves: non-committal poses, white backgrounds, mostly taken in close-up to avoid details of clothing and the wider surroundings.

If ‘everything in Warhol is phoney’ as Baudrillard believes, what happens when his subject of interest is decidedly not phoney but very much alive? In short, the answer is it becomes a morbid object: his process renders these people separate from their public image for an instant and it’s not difficult to imagine Warhol’s bland glee as he confronted such people with his photos of their real likenesses moments later.

‘Look, you’re ordinairy.’

I imagine him being rather like a ghost from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, specifically the ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, daring his subjects to look at their future graves. ‘Your nature intercedes for me, and pities me’, Scrooge pleads. ‘Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life!’ I wonder how many of Warhol’s subjects would have begged the ghost for a similar offer, especially if they could see how prescient the deathly qualities in the Polaroids were. Perhaps due to sheer chance, these ominous creative objects did foretell a future in which their demise was uncomfortably close.

It’s fitting that the Beatle Warhol chose to photograph (equally likely because of Lennon’s base being New York at that point) was the one who was to be murdered in broad daylight several years later on a street not far from The Factory. Equally, the artists Warhol photographed would more likely than not find themselves facing death early on, in particular Basquiat, Mapplethorpe and Haring who all died of AIDs related illnesses by the time the 1980s concluded. Warhol himself was soon to follow due to unforeseen complications from gallbladder surgery.

For someone so obviously fearful of death in a physical sense, his playful use of it in his Polaroids is surprising. It’s not just for its aesthetic that Warhol’s Polaroids resemble a taxidermy collection; it’s there in the histories of his subjects. He was drawn by chance, though it’s not unreasonable to assume that he could envision the early demise of his subjects, simply because they were so engrained into the public conscious. Of course these casual photos would gain some significance in the future; these were the most famous people in the world.

Death is everywhere and it was Warhol who let him in.

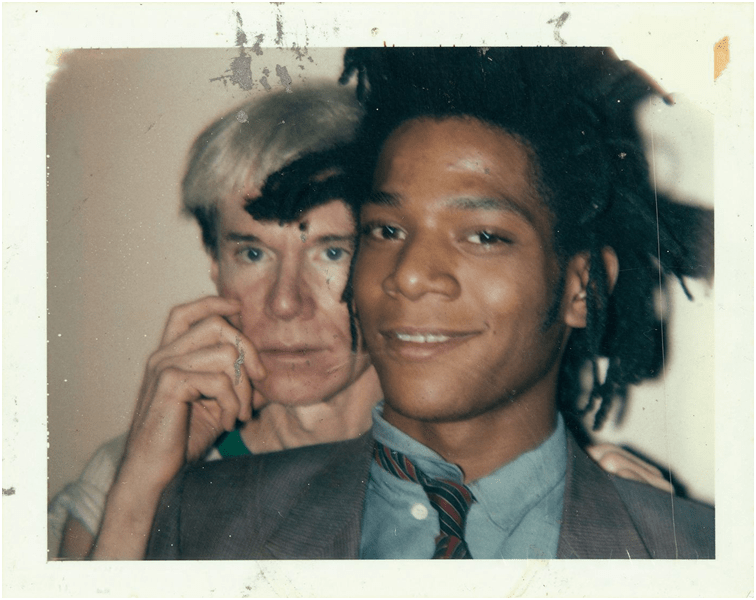

Some of the Polaroids seem more than a little self-aware, and it’s not hard to believe that they had the quality of a personally conducted sociological study. They are Warhol’s anatomy of celebrity. One Polaroid shows Warhol standing behind Basquiat in a battered photo obviously not taken by Warhol himself. Perhaps it was taken by Basquiat holding the camera out to create a joint selfie. Warhol would have loved seflies; today we volunteer and opt in to his processes of hollowing and projection, ironically as a way of proving and legitimatising our lives.

It would be too easy to consider this Polaroid a casual photograph, but it’s not difficult to imagine the conversation leading up to it; Warhol pulling his friend aside (‘Let’s take a photo!’), quickly fumbling the machine into the other artist’s hands and angling it just right before snapping. Basquiat looks bemused by the prospect of their shared image but Warhol lingers ominously behind him like a spectre. A few steps further and it would have looked like a portrait of Basquiat with a ghost accidentally caught looming in the background.

Warhol cannot be truly destroyed as an ideal by his own processes because he already doesn’t exist properly as a person. The erosion by his processes had already taken effect and it went as far as it could without him physically dying. He is an entity floating around in the pipes of the mass media system to the point where he’s barely there at all.

It’s fitting that his skin became so translucent and his hair so light as to fade into the air like wisps of steam. He’s like a vampire looking into the mirror; he’s absent and seems to enjoy that absence. He possesses an awareness of this, too, and makes jokes about it later in his Polaroid photos. The most obvious is one that feels in some way connected to his Polaroid with Basquiat, at least compositionally in the way that the figure at the forefront of the photo seems unaware of the figure directly behind them.

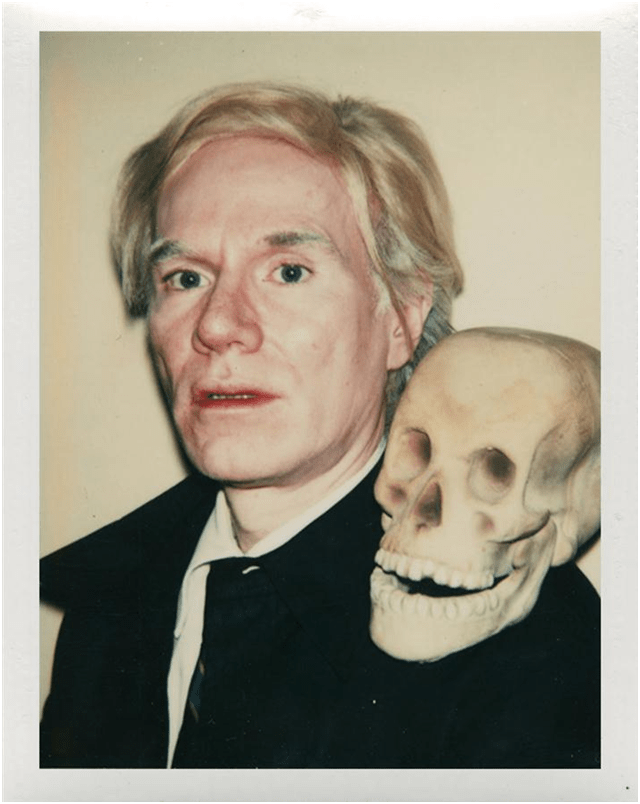

Warhol is looking beyond the camera in this photo, though there are several from the same shoot. He almost certainly didn’t take it because a sort of balancing act is going on, his arms rigidly by his sides. On his shoulder is a grimacing skull, a rather cartoonish prop that looks fitting for an American Halloween party or a ghost train in a faded regional seaside resort. The photo would be light and comedic if not for Warhol’s own particular grimace. His Yorrick is a mocking skull, one that makes light of death in the same manner as the artist did.

Warhol is wearing a black mac and white shirt split down the middle by a black tie. He looks like a cross between an undertaker and a stylised version of the reaper himself. If any work by Warhol could be said to be honest in its intentions, then it is this singular Polaroid, and even then honesty still feels wrong for such a contrived image. It’s the closest thing on offer in his catalogue of fetish, consumerist objects beyond an ironic gesture.

The Polaroid is an admission, a confession even. He is the embodiment of a machine that has destroyed people slowly and publically for centuries, and here he is in the white light of the flash, looking on without emotion as the erosion fails to even scratch at his lapel.

He renders death a cartoon.

‘Death can really make you look like a star,’ he once said. This is Warhol’s most important admission. Celebrity never truly dies, it merely comes and goes. Warhol’s Polaroids make for a fitting purgatory for stars to dwell in.

In Warhol’s Polaroids I see the murder of a celebrity’s glossy image – the imagined projection we all on some level buy into. This process is deathly. The artist was only too glad to bring Death along to the party, thinning his subjects again and again through his various crafts and processes, especially his famous lino prints.

In the Polaroid camera he found a machine that reduced these complex actions to the click of the button. And, of course, the very camera that this most perfidious of artists used went up for auction for $50,000 dollars only a few years ago: another compelling irony to add to the mythos. While the rarity of Polaroids makes the idea of images doused in the presence of historical figures understandably worth something, it’s absolutely fitting that this basic machine is now seen as yet another valuable artefact in the artist’s endless celebration of emptiness.

In every Polaroid by Warhol, I see that absurd skull stuck on his shoulder. Warhol was beyond death by the time his creative machine was up and running.

He knew all too well that you can’t kill a ghost.

2 thoughts on “Presence, or Polaroid Ghosts (Part 16)”