Not all memories are as sacred as Tarkovsky’s. If time can be expressed in photos taken by the public at drunken parties, then it can certainly present in work by other artists, even those driven by less transcendental aims than Tarkovsky.

Considering this, the first body of work that comes to mind is that of the American photographer William Eggleston. The Tennessee photographer was pivotal in creative photography’s shift towards colour and away from the dominance of black & white. His ordinary subject matter, saturated with delirious colour, re-mythologised the everyday of twentieth-century America, rendering it a sort of Xanadu where the eye was filled with endless blue skies, vibrant branding and gas stations, simultaneously alike yet different to Walker Evans. It’s easy to see why Eggleston’s subject and style of photography would, therefore, suit the Polaroid camera. However, it’s surprising to find his work with the machine all too brief.

Eggleston’s flavour of Southern Gothic is heady to perceive in any format. The richness of 35mm certainly suits his work more generally than Polaroids. Like Evans, his great inspiration, as well as Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson, his shift to Polaroids seems more out of curiosity than necessity. He certainly failed to fall under its spell like Evans did.

It’s easy to believe that seeing a photo printed so quickly and succinctly would be refreshing for a photographer whose process of dye-transfer printing required just as much attention as the photography. Yet the Polaroid comes closer to Eggleston’s stated vision of photography; that he would capture the world as it stood with the materials that it provided, dismissing anything superfluous. ‘I had the attitude that I would work with this present-day material and do the best I could to describe it with photography,’ he said. ‘It was just there, and I was interested in it.’

I doubt there’s a photographic form that is more ‘just there’ than the Polaroid.

What’s interesting about Eggleston’s Polaroids is not how his style and subject transferred with such ease to the new form, but how its relationship to time and memory seems more overt. Eggleston’s style was certainly similar to Evans’ in that his approach ephasised the everyday street furniture as a subject matter; what was seen (and not seen) by Americans in their day-to-day lives. He wanted to show how beautiful these things were in all of their ordinariness; in their being there as he said.

His colours are rich and at times overwhelming. But his 35mm work often feels static, even when people and objects are on the move within them. If cars were there, they were pristine and parked up, as if the machines were posing. This was a testament to Eggleston’s skill as much as anything else but it actually renders some of his more audacious 35mm photographs with the feeling of simulation which feels contrary to his own aims.

It may have as much to do with the falsity of American street life, the adverts promising endless dreams, the cars promising endless adventures, the provocations promising endless pleasures. But they feel frozen, such is their detail. Instead, I prefer his Polaroids, a form he produced several celebrated images with but by no means a wealth of work.

The key to Eggleston’s use of Polaroids was chance; a character so fleeting that’s easy to believe that reproductions of the finished images may fly off the page at the slightest gust wind and may never be seen again.

The photographer’s subjects are mostly the same – highways, streets, gas stations, advertising – but, with the Polaroid camera, Eggleston imbues them with the moment, a time so swift and kinetic that cars threaten to drive out of the shot, drinks threaten to spill and shops threaten to close before the Polaroid has finished developing.

There’s a contradiction here, between the subject of the Polaroids and the feelings they express. These feel like places where life has ceased to turn, except for those just passing through. They are forgotten places, empty telephone boxes, banks closed during lunch hour, parking lots where the weeds grow. It’s easy to see how the images influenced Wim Wenders and Robby Müller to a degree; the characters of their films share that same quality of passing through. Time here is different to Tarkovsky’s patient Polaroids as Eggleston implies his own momentum within the photos. It is he who is on the move, just like the unseen figures that brought the cars and bottles of coke to his attention.

Eggleston was not searching for home.

If the noeme of photography, as Roland Barthes obtusely called it, was the aspect of photography capturing the ‘That has been’, Eggleston’s Polaroids are more suggestive of the ‘That has just been.’

Right then, there, did you see it?

Just now, in fact.

Blink and that car will be gone.

Maybe you’ll smell the exhaust fumes but Eggleston was lucky to see it all.

With Eggleston wandering around Mississippi armed with his Polaroid camera, it’s not difficult to see that the reason for taking his fifty-or-so Polaroids was research. Just as many film directors have turned to the Polaroid for researching locations and images, Eggleston’s Polaroids are considered dry-runs for his main work, complimentary at best.

Yet to my eyes they possess a unique sense of time all of their own, even when portraying the same subjects as his more celebrated, technically gifted images. The fact that the Polaroids were only very recently published in a volume tells how they generally sit in the more respectable appreciations of his work. But his wandering nature is better preserved in them because the form allows it to remain.

The raggedy reality of travel isn’t masked by the rich, heady colours or lavish printing techniques. His wanders on foot and bumpy journeys by car are there, the chance moment before life continued around him, taken and made the most of. With Eggleston, it’s not unbelievable that he snapped his shots and just got back on the road straight away; gambling with their development on the hot dashboard of his car.

In this sense, Eggleston’s Polaroids resemble casual memories more than Evans’ images. They may have a better composition to the everyday Polaroids of the public but his photos share their same unpretentious sense of time. They teeter on existence. His Polaroids have more in common with those taken by the public than I imagine the critical writers on his work would like to admit.

Time and journey become one. Trains are about to leave, Dodge Chargers are about to pull away, cokes are about to be tipped over. Eggleston aims his camera, snaps and moves on. His workman approach is refreshing and devoid of over-thinking or obsessive consideration.

I especially love his images of coke bottles as they seem so precarious; time is ticking in these photos due to their diminishing use. Those glass bottles are even more disposable than Polaroids. In one Polaroid, we see a range of used bottles piled high ready for collection. You can almost hear the rattle of them as a lorry on the long haul pulls in, the jittering glass causing strange music among the sounds of the highway diner.

It’s just another moment in Eggleston’s day, preserved forever but still retaining the feeling of time passing, better things awaiting, not a moment to lose.

Quick, quick. Life’s too short for idling.

In another photo, perhaps my favourite of all of his Polaroids, a bottle of coke is sat half-drunk and lonely in the high afternoon sun on a sidewalk. It’s perched on a brutal concrete pavement in a way that I can’t decide is either incredibly natural or absurdly contrived. Its shadow is perfect and full but the bottle is half empty. It seems heavy with caffeinated symbolism, if symbolism in a bottle of coke isn’t too ridiculous (it obviously is, which is why I love Polaroids in general, daring us to make fools of ourselves in our pompous appreciations).

Appropriately, Eggleston found reading photographs of any sort bizarre as an activity. ‘A picture is what it is and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them,’ he said, ‘or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them… I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.’ His photograph resists words because they are so of that moment, and, like many Polaroids, resist the increasingly dominant graduate-speak of art criticism more generally. Imagining what their information cards would say if housed in a gallery is enough to send shivers of horror down one’s spine.

Where is the drinker?

Did they leave in a hurry?

Is it Eggleston’s drink, posed in the style that may replicate today’s banal trends on social media?

#LovingIt

In the end, there’s only the image.

Thank heavens.

The taste of warm cola fills my mouth when I look at the photo, transported for a time to the hot, empty highway where Eggleston stopped for a moment. If the bottle wasn’t Eggleston’s, then the photo becomes stranger, suggesting the personal time of someone else being interrupted; the disruption caused by something important enough to leave a half-drunk bottle on the sidewalk.

Who does that?

Why?

You can feel the haste of it. Whole imaginative worlds open as to what exactly could have taken someone away from this particular moment. Photos such as this remind of something the writer Alain Robbe-Grille said about human memory. As his own novels and films dealt explicitly with the fallibility of memory, I trust his words. ‘Memory belongs to the imagination’, he wrote, ‘Human memory is not like a computer which records things; it is part of the imaginative process, on the same terms as invention.’ Eggleston’s Polaroids realise this acutely, but so do most Polaroids. It’s simply more obviously a part of Eggleston’s Polaroids as he was doing it off-the-cuff.

If memory does belong to the imagination, then Eggleston’s Polaroids, by sheer chance, tap into the memorial of the moment. It sparks our imaginations with what is just about to disappear, the people who have just wandered out of shot, those who have hastily left their coke in the unbearable sunlight of a barren car park on a southern state highway. It’s photography of ghostly moments: after the fact. How close they sometimes feel to life which often resembles nothing less than a moment that has somehow escaped notice; when our potential to be a part of it has long gone.

Eggleston’s Polaroids make me wonder about the lost moments of my own experience. It makes me almost paranoid for what was potentially left unnoticed, what was missed through lack of experience or bull-headed ignorance. Perhaps those awful moments of tedium, which extend at length in my memory, were actually interesting, and I was simply too stupid to realise it. Perhaps if I’d been a photographer during my teenage years, I would have found ample subjects for work if I’d just looked past the day-to-day necessities.

This small collection of Polaroids makes me question the world that was once around me.

As more and more things become digitised and beyond tangible, perhaps even this banal collection of mass produced objects and plastic that surrounds me now and constitutes my possessions will take on new, important meanings when the last aspects of lived experience are downloaded from reality onto the Cloud. It’s a thought that horrifies me even if I adore the fleeting fragments of Eggleston’s photography; that artists like him showed that memories shrugged off as banal were worth preserving for posterity. And it’s ultimately posterity that drives photography no matter what guise it comes in.

There is despair in these machines.

If Tarkovsky reified the personal aspects of his everyday experience, then Eggleston showed something more general: the stories and interest in time that has barely registered. I want to see more of these moments, these shards of lives on-the-go. But, unlike the reality of their subjects, they’re finite and impossible to recreate. For someone who, by his own admission, was ‘at war with the obvious’, it will always surprise me that he didn’t see the Polaroid as the ultimate weapon in winning that war.

Yet, as the photographer said, ‘Photography just gets us out the house.’

Eggleston was highly influential on the documentary photographers that followed him, revealing the potential subjects found and ignored in the everyday world. One such influence was on the so-called Boston School of artists that emerged in the 1980s, the most famous member of which was Nan Goldin.

Goldin, like Eggleston, experimented a great deal with Polaroids along with David Armstrong. They played a vital role in the movement they were part of, even if she only used them in a similarly haphazard fashion to Eggleston. The resulting work of these photographers is sodden with time. Unlike Eggleston, however, Goldin was interested in the details of the subject rather than the potential abstraction within it, almost deliberately placing each image in as detailed a context as possible.

Though Armstrong seems to have used the Polaroid camera more, Goldin’s results are more doused in time and memory. Like Eggleston, it was clearly not her main medium, so her relationship to it is more experimental and risky, barely recognised at all in contrast to her main body of work with 35mm. Yet the Polaroid is a machine that nullifies the complacency of more established artists which is enjoyably contradictory to the camera’s efficiency and ease of use.

You can’t over-think a Polaroid. It won’t let you.

Goldin was born in Washington but grew up in Boston. Though predominantly known in her work exploring the various subcultures of New York in the 1980s and beyond, her time in Boston collected her work together into the ICA-christened Boston School, alongside Mark Morrisroe, Gail Thacker (another noted Polaroid photographer), and a number of others.

Though the grouping was retrospectively coined as a catchbasin for an aesthetic, the general ethos was one that suited Polaroid photography; for the idea was to delve into the messy reality of life, bringing the viewers closer to worlds that likely passed them by. It also meant Goldin was subject to a number of criticisms, in particular the glamorising of substance addiction; turning heroin dependency into a commodified, fashionable aesthetic much-aped today by the more hipsterish end of fashion magazines. No matter the pain of those whose lives she documented, those worlds feel easily recognisable in an age of grungy, deliberately run-down photography popularised by magazines like Vice, I-D and Dazed.

The chief irony of this is that the people in such photographs today are arguably rich and middle-class rather than living the destitution in which they’re styled. They wear other people’s pain as a mask to occult their own undeniable privileges.

Goldin, Thacker and Morrisroe skirt these issues as the aesthetic seems to be one born of reality rather than one explicitly exaggerated or manipulative of their subjects. It was one made with the tools that were easiest to use and cheapest to hand. A point came in Goldin’s career when she realised that, no matter what the historical content of her work, especially in documenting the trauma of the AIDs epidemic, such was the close proximity to her subjects, her work inescapably spoke of personal and intimate memory. In fact, few works have managed to balance this intimacy with such a visceral reality.

It must be said that Goldin’s Polaroids are sparse in comparison to her other documentary photography. They largely consist of quiet self-reflection, taking the odd photograph of herself or David Armstrong during their day-to-day lives. These are closer to Polaroids taken by the anonymous public than a widely celebrated artist which is why I like them.

I love her notes to herself, a sort of tautology that renders these personal photos dead-pan ironic. It’s like stumbling on a private letter or diary entry that wasn’t meant to be found. Yet they also suggest a future audience. Their blurriness makes them feel closer to real memory; half-seen, half-remembered details that refuse to fully focus in the mind’s eye. I wonder what the photographer thinks looking back on them, whether her aged self sees the face in its blurs and saturations. Did her past really look like that?

In reality, Goldin considers her own photography naïve in its ability to prevent loss. ‘I always thought if I photographed anyone or anything enough,’ she said, ‘I would never lose the person, I would never lose the memory, I would never lose the place. But the pictures show me how much I’ve lost.’

This partly explains why she captioned her Polaroids, even the obvious ones. She is, by her own admission, afraid of losing the memory. Time is present in her Polaroids, not because she is afraid of losing the past (Tarkovsky was hugely afraid of this by comparison), but instead losing the very memory of these people; people who were subject to a disappearance from the public eye. In the historical context of her photos, this is understandable as a whole generation of people were dying, and there was a dangerous reluctance to discuss or talk about it.

For Goldin, memory is key because she wants to feel as close to the people around her as possible; keenly aware that there were literal, upsetting deadlines to the time she spent with them. ‘My work is mostly about memory’, she believes. ‘It is very important to me that everybody that I have been close to in my life I make photographs of them.’ Though this took the form of 35mm more than Polaroids, the Polaroids that do exist show that the DIY ethos of the Boston School – part punk zine, part underground gay club – found a perfect medium in the camera. This comes across, too, in Morrisroe’s handful of Polaroids which revel in the same grunginess, but most of all in Gail Thacker’s images.

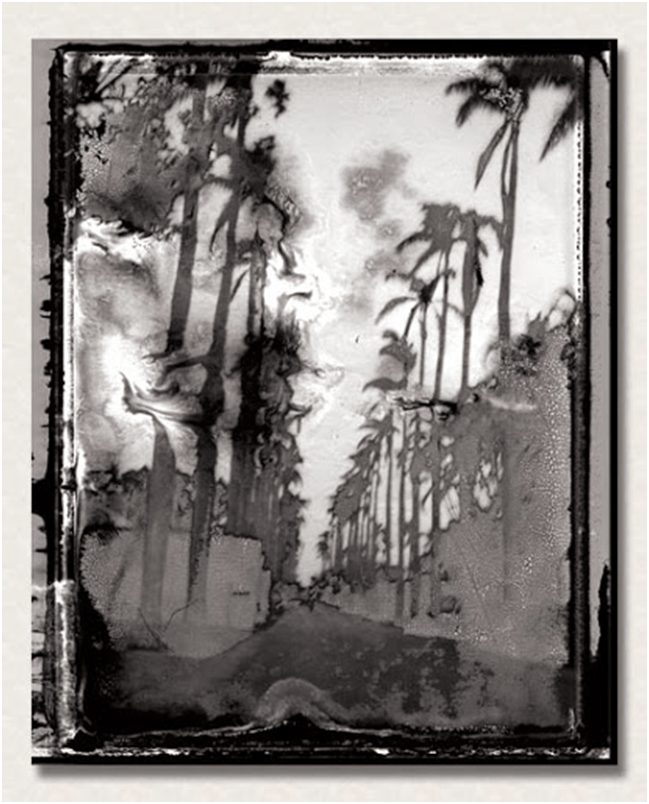

Thacker was given a very particular type of film stock, the 665 Positive/Negative black and white film. Black & white Polaroids in themselves have a different feel to virtually every other Polaroid mentioned in this book. They speak of memory but not quite in the same way.

Black & white naturally insinuates the past to some degree because so much of the past is rendered without colour. Thacker uses it in intriguing ways, similar to Goldin’s photography. The disintegration and distortion of the moment is captured and dialled up, like a woozy, druggy nightmare. They also do away with the typical formatting of the white boarder that Goldin and Morrisroe enjoyed using. It is purely the photographic element that Thacker deployed. The colours may be reduced to shades of grey, but the presence within all of her Polaroids is overwhelming.

Considering the distortion, which was by the artist’s own admission created initially by accident, Thacker has surprisingly always taken care of her photography. ‘The only thing I had control over was my relationship with these Polaroids’, she admitted. ‘This was the only way I could stop time from destroying the rest of my friends.’ Clearly there’s a similar emphasis to Goldin’s photos. They did, after all, share the same friendships: the same people were dying. But Thacker’s work is quietly about the very disintegration of time, even in her attempts to stop it. They may dam the flow for an interlude, but their own distortions already attest to a future when they will merely return to nothing.

I particularly like Thacker’s image of a palm tree-lined road, which is more likely California rather than New York. I like it because it gets to the heart of her photography without showcasing her usual subject matter. The photo was commissioned as part of a series towards the end of the line for the Polaroid Company around 2008. It was a series loosely labelled The Last Polaroids, as if the end of line for Polaroid stock would produce images that showed their vision of the world to be disintegrating as well. Thacker was the perfect artist for this as she would have likely produced images of this ilk if Polaroid had stated that the stockpile of Polaroid Film would last for several millennia to come. Either way, even with hindsight of Polaroid’s bounce-back and refreshed popularity with a new generation of photographers, Thacker’s imagery is enjoyably pessimistic.

It captures an atmosphere I associate with the films of David Lynch and Kenneth Anger’s salacious Hollywood Babylon book; the prim and proper vision of paradise destabilised by the rotten underbelly writhing beneath the white fence-posts and palms. It is HollyWeird writ large; nasty rumours of studio bosses, Peg Entwistle’s suicide from the big H, Errol Flynn’s secret cameras and peep holes. Reality bubbles with the threat of oblivion, Thacker having stared into the everyday and seen the end of the make-believe world. Hollywood was dying.

I imagine that if the photo was in colour, it would segue into more psychedelic reverberations. In stark black & white, Thacker’s Polaroid feels like the end of time, a last glimpse of Hollywood before it fell into the void. It’s also the only photo I’ve seen by her that feels like it’s cheerleading the destruction – an enjoyably typical New York view of the West Coast – rather than attempting to stem it. It’s far from Thacker’s more celebrated images, especially those collected under the title of Fugitive Moments. It’s a title that could equally map onto Eggleston’s smattering of Polaroids, if Eggleston’s were rancid with loss and the grime of 1980s New York, that is. Moments are trying to escape Thacker, and she takes delight in decimating them when she catches them.

Thacker’s Polaroids are rich in time because they wear their distortions confidently. They have been put through life’s blender and said no to Botox. She’s a contradictory artist when discussing this aspect of her work, perhaps explaining the rational from her era; one that was forced to choose between absolute loss or indifference.

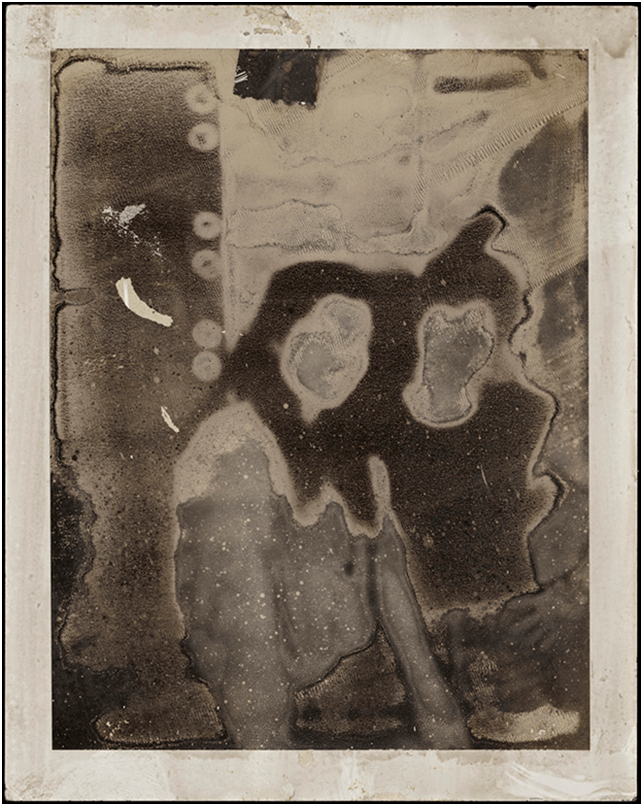

On the one hand, Thacker took great care of her Polaroids. They were the only thing the artist felt she had any control over, the only plug to stop the flow of death. On the other, when exercising this control, it became something more ridden with chance, even destruction. ‘I think of the Polaroids as living things. They’re symbolic of the passing of time, and our decay. There’s an impermanence to them that shows how short and fragile this journey is.’ To be absolutely true to the passing of time, Thacker helped the Polaroids along by treating them with as much hedonism as the bodies of her subjects.

‘I would wrap them in plastic,’ she said, ‘all stuck together. I wouldn’t rinse them off. I’d put them in a closet, under the mattress, something ridiculous. Then I’d forget about them. Go back to them a month, sometimes a year, later. And there it was.’

People decay under her bed, turning rancid in Hell’s Kitchen.

In another Polaroid, this distortion becomes extreme to the point where the figures in the photo become little more than shadows of whirls that once were. Faces are voids where personalities once existed. Bodies have melted into the background. All has become shade and shadow.

The human body is finally hollowed by existence.

The world is burning in Thacker’s Polaroids, to the point where even colour has evaporated. In reality, the real lives at the time weren’t that far off this destruction, a sense of disappearance haunting a generation as bodies and Polaroids rotted together. Thacker’s Polaroids are drenched in memory, not because of the poignancy of what they capture but because what was captured is organically breaking apart, just like we do. Hers is a ghostly practice, one that accepts future loss and pre-empts the haunting before it happens.

Polaroids are honest about time and our relationship to it, Thacker’s refreshingly so. It’s easy to see catharsis in this, the same catharsis I find in Polaroids gone mouldy in old markets, faded by the sunlight in forgotten frames or crumpled in boxes left in attics. They are a form that age with us and have the scars and bumps to show that they came along for the ride.

Time is just as merciless to them as it is to us.

I look down at a scar on my arm and see its story in my mind’s eye. I look towards a Polaroid of my own, crumpled at the corner, distorted by a drop of rain and I travel back instantly to that moment of lived experience. Living is a destructive thing to experience. As Thacker herself admitted, life can be like that, which is why Polaroids were such a fitting medium for her. ‘You try to control it, but it’s still gonna do a little bit of its own thing. I found that the Polaroids were doing something similar. I really related to that.’

…

It was a long while before I began to follow in the steps of Marcel Proust once more. His memories cascade like falling buildings, and journeys foot-stepping him fall equally into stops and starts. They contain a layered rhythm all of their own.

Some years after visiting the smashed building that was once his home in Paris, I ghost-stepped Proust again, simply for pleasure rather than work. I’d given up hope that visiting the lonely spots of writers could provide some insight into their lives and books; instead it merely threw into contrast things important to me as the follower rather than them as a subject. Yet this particular memory did suggest something of Proust: namely the irony of memorialising someone whose whole work was an attempt to memorialise their own person experience. He’s remembered twice in France; once by himself in his semi-fictionalised search for lost time, and again by the French public who spur on his memory for more basic reasons.

The treatment of Proust in some of his old haunts today is amusingly touristic, having spawned a minor Proust industry around the spots that inspired his work. The irony, of course, being that he could never bring himself to name the places fully in his work, as if the loss of that time was too painful to give them their truthful location. He carried his sadness within him, weighing his memories and the present tense in which he recalled them.

The place in his work that I was really interested was the fictional Balbec, or in reality, Cabourg on the Normandy coast; a lavish seaside resort that must have been breathtaking during La Belle Époque but is now merely quaint with a few gloriously busy designs and buildings nestling between the typical tourist traps designed to lure Parisians for a few days each summer.

Cabourg was once Balbec, the coastline and the town’s Grand-Hôtel essential in Proust’s retelling of his childhood. The whole of the coastline beyond the town is obsessed with his recollections. In fact, it’s harder to find a large older restaurant or town along this coastline that Proust didn’t have a connection with. As with all memorialisation, there’s a feeling gaudiness. Proust’s room in the Grand-Hôtel, number 414, is preserved as it was but the remainder of the hotel itself is notoriously modernised, with a range of awful decorations, infamously including urinals in the Men’s toilets shaped like gaping mouths.

None of this put me off visting as it was a day out. I walked it with an ex-partner, someone often bemused by my reasons for wanting to visit places. She’d treated my Polaroids with initial curiosity but had since become used to me carrying the cumbersome machine around, one which brought attention whenever I used it.

The day was busy in Cabourg, sunny but breezy, meaning great spectres of sand were kicked up, making people cower and rub their eyes with annoyance. Masks were enforced due to Covid-19 though it mostly felt like a normal day. Every shop in the high street had images of Proust in the windows, a range of merchandise for sale, from tins of Proustian Madeleines to soap with the Proust brand on, and various objects all shaped like his moustache. There was an even a Covid safety poster which used a cartoon version of Proust to promote the wearing of facemasks, his distinctive face still recognisable by his Belle Époque attire and the moustache bristling under the mask. It was absurd.

We sat with a coffee and a sandy croissant, enjoying ourselves as much as was possible with a pandemic floating around. The Grand-Hôtel loomed over us and the beach, people jovial yet cool in that way I naively associate with the seaside dramas of filmmaker Éric Rohmer.

I wanted to remember this day, for I knew that I would soon be treasuring even the most basic of memories as the winter arrived and the Corona virus crisis would ensue further. It made a long distance relationship to France utterly impossible to maintain. My then partner took hold of my arm as I aimed the camera at Proust’s hotel, the hotel where the sight of boats from the window transported him from his bed to imaginary berths where the sea swayed him.

We walked further to let the photo develop, noticing a bench dedicated to the filmmakers Agnès Varda and Jacques Demy, which we sat on. We saw the likeness of Proust’s hotel emerge, and it felt like nothing less than a physical rendering of memory, an inedible Madeleine. I could already see us looking back on it, the feelings of that day returning; the gritty feeling of sand having been blown into our food.

I look back on that Polaroid now, long since split from that partner, and I feel filled with the same overwhelming nature of memory that Proust felt on realising so much that he loved was no longer in reach. I feel my ex’s arm whenever I look at the photo, the memory heavy with pleasure but aware that the moment has long since moved on.

Proust called his final volume of In Search of Lost Time, Time Regained (Le Temps retrouvé). The act of his recreation was on some level successful. He’d rescued his memories from the clutches of time’s passing.

Polaroids are also time regained.

The Polaroid ignites within us the spectres we collect in our memory. They materialise before our eyes moments long deceased, or even still right there in front of us. We can see the idiosyncrasies in what they memorialise, but more importantly we can imagine in great detail the road that led there. They reveal nothing less than the human soul as it lives in the ongoing moment.

I look to the photo of the Grand-Hôtel, time growing in its top corner like mould, already taking away the life I lived and shared with someone. The mould may grow over the whole image one day in its strange design, but so will the wrinkles on my skin, the flesh on my ex-partner’s arm that I feel still clinging on with affection as she sits by the sea in that frozen moment. It grew with us until it eventually outlived us. And how much more beautiful the light and memory of that damaged world often is. It’s the ultimate Madeleine and there’s no comparison to its tastes; its time regained.

These pieces continue to be so good, so thoguht-provoking. This one is especially nice. Thank you.

Thank you Terry, only wish you could be reading on the page rather than a screen!

This Polaroid series is an absolute treasure.

Thank you!