TL;DR – I love rubbish First Doctor stories.

I was on a car journey earlier this year heading to midlands with Mark Gatiss, Jon Dear and Chris Lincé. It was painfully early and we were on our way to hunt out some of the locations used in Lawrence Gordon Clark’s BBC Ghost Story for Christmas, The Signalman (1977). The conversation covered exactly what you’d have expected from anyone who knows any of us – old and new television, actors, horror – but an inevitable question came up pretty quickly, one that usually fills with me dread. “Come on then, favourite Who,” Mark asked. My favourite episodes of Doctor Who are a tricky thing to explain, to say the least.

Obviously this is the sort of bread-and-butter question that fans thrive on. DWM has a minor cottage industry of asking the question every few years and releasing a glossy magazine sharing the, mostly inevitable, results. Even with the difficulty of the task in hand and juggling how you personally measure it, my answers almost always raise an eyebrow, to put it politely. I’ve usually assumed that such a question actually means “favourite” rather than very sensibly thought out, determinedly objective “best” (which would definitely result in very typical answers on my part barring one or two exceptions if requested), but it still doesn’t excuse me from what I generally usually answer. On shyly admitting the great shame of some of my great loves of Who, Jon (who had, it must be said, been subjected to my heresy before) muttered a quiet “fucking hell”, Mark exclaimed a somewhat louder “What!?” and Chris deferred in what I presumed was polite silence.

The simple reason for this reaction is that I have a real soft spot for a kind of story that I call Hartnell Greys. Though a few aspect of Hartnell Greys go beyond the William Hartnell era (more on those later), the criteria for the Hartnell Grey is relatively simple:

- They’re usually a First Doctor story, obviously.

- Their scale is small, either by choice or by the production team’s ambition amusingly hitting the hard wall of budgeted reality.

- They evoke the silver age of science-fiction and are usually a quaint cousin of space age SF.

- They’re almost always utterly naff or daft, but in a way that, though characterised by the more general fan as dull, boring and utterly tedious, I find relaxing to the point of a strange, cosy ambience.

Whenever I discuss my love for these stories, I sometimes feel akin to those strange people who you occasionally meet that like that sound hairdryers and washing machines; there’s something a bit weird about it all. Is it deliberately contrarian, an attention-seeking “look at me and my weirdo taste” cry into the void? The best way to explain it is to delve into some of the stories that tick all of the boxes for me and how I first came across them.

In the halcyon days of the 1990s (no apology for this here, I was born in 1989), being a Doctor Who fan was really great, contrary to either the older grumpies who had to make new toys to play with or those post-2005 fans too young to have appreciated it (and who, rather hilariously, quiver in terror at similar possibilities currently faced by the show). One of the treats of the period was finally being drip-fed access to older stories on VHS and on UK Gold which, still being a child, I watched in omnibus form with the kind of glee I imagine vaguely echoed earlier generations watching on Saturdays (or whichever day of the week JNT had been lumbered with in the 1980s).

The strange pleasures of VHS recorded Who will in itself be an acquired taste; the bizarre combination of stories that relatives (or friends of relatives) had, with some begging, recorded in bulk onto blank Scotch VHS tapes; the way the endless adverts seemed to become part of the viewing experience, to the point where they could be quoted with as much accuracy as the stories themselves (Earthshock will never not remind of an insurance advert which descended into a kitchen dance scene to Nat King Cole’s “Let’s Face the Music and Dance”, along with a woman diving into a cup of Cadbury’s hot chocolate). But the point in raising this nostalgic haze is that Hartnell Greys worked best in this format.

UK Gold’s scuzzy 16mm prints of Hartnell episodes elicited great joy anyway, but combined with being a bit naff and boring were raised to the kind of ambient, transcendent excellence of a Brian Eno album. The first of these I watched was the wonderful The Rescue.

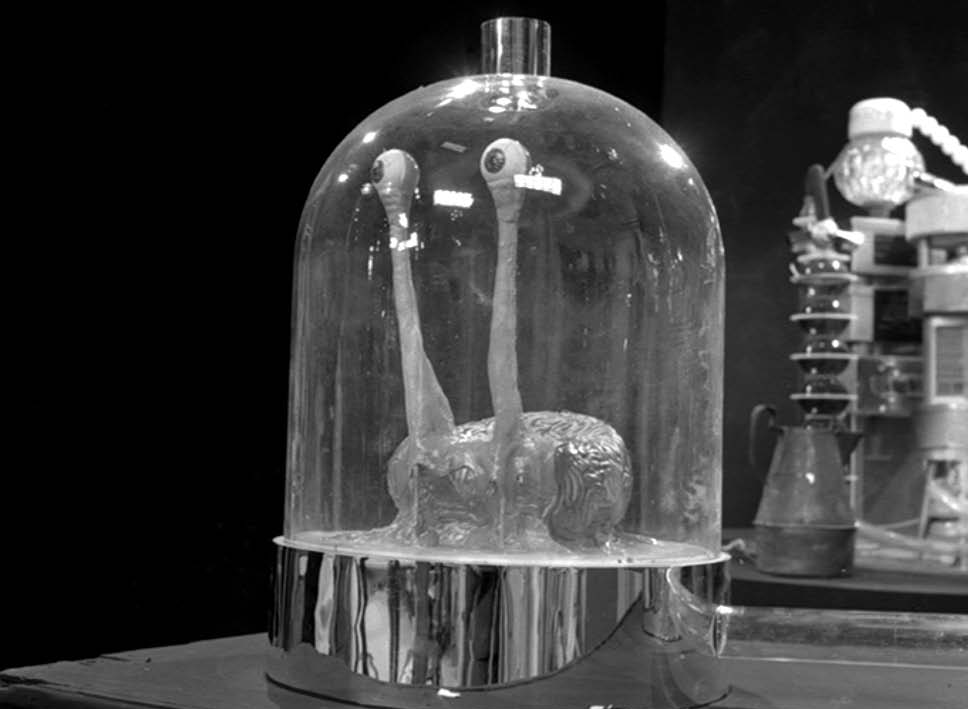

The Rescue is, in a sense, the perfect Hartnell Grey. I remember an old DWM article describing it as a script-editor’s piece; a technical change of tone and direction for the show by David Whitaker in that its main job is to showcase Maureen O’Brien’s brilliant Vicki. But the story itself? A perfect Hartnell Grey. It has two daft monsters, both with equally daft names and, with this being a Hartnell Grey, one of them isn’t even a monster by the end. Its scale is miniscule, made even more miniscule by the two episode format. Its stakes are small, its production occasionally shaky (spot the crew member lurking in the shadows behind Sandy in the cave as he flops about) and the general impression among fans that it’s a bit of shoulder shrug: it’s not Inferno nor Androzani.

But, hand on heart, I’d much prefer to put on the old, worn VHS I eventually bought of The Rescue than those two stories, or most others. It’s like a warm cup of tea. My love for The Rescue wasn’t quite the story that elicited the responses earlier described, however. It was my true love: The Space Museum.

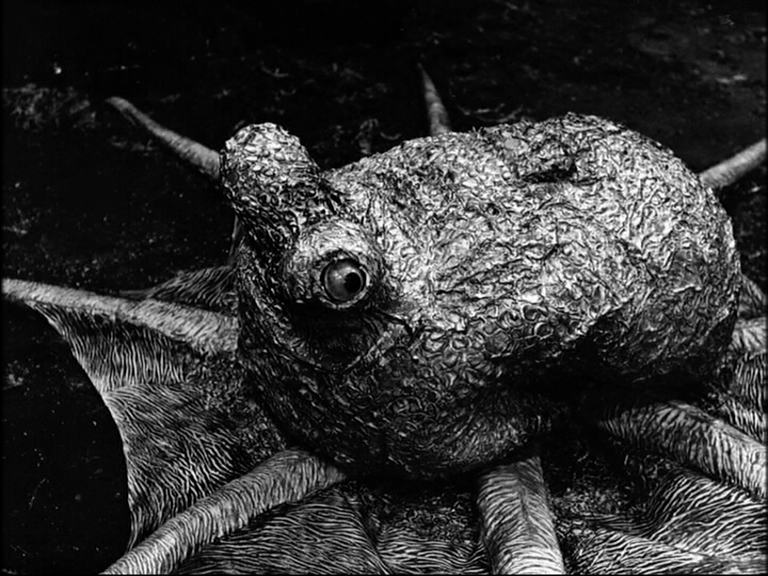

I’m not alone in enjoying The Space Museum; a story infamously boring, highlighted further in its boringness by having an undeniably stunning opening episode. Writer Rob Shearman garnered a whole (excellent) documentary extra about the story for the DVD release, but I somewhat disagreed with his assessment that the story’s three weaknesses were episodes 2, 3 and 4. In fact, I love these episodes. Aside from their humour (actual witty humour, not the pizzicato string-scored side-eye irony of modern television), the sheer relaxed approach to the story and its utter non-revolutionary revolution make it genuinely enjoyable.

Sometimes in Hartnell Greys, it almost feels like the wheels are coming off the production and, in that sense, it’s even more interesting. However, viewing in this sense isn’t detached. I’m not laughing at these stories. They’re genuinely pleasurable. I remember an afternoon where I enjoyed The Space Museum so much, I watched it all over again. I double-billed The Space Museum with The Space Museum (a difficult task considering it shared a tape with the two surviving episodes of The Crusade making rewinding to the exact spot difficult without a fragment of William Russell acting in Ian Levine’s lavish house).

I love the fact that The Space Museum is, by the nature of its own story, utterly self-contained in its perilously small scale. It’s hampered by it. The Doctor, Vicki, Ian and Barbara may get lost in the vastness of the museum, but the quintessential aspect is that it’s utterly boring. How anyone can not find this amusing is beyond me, but again, even if they don’t, the unusual comforts of watching the story are difficult for me to convey but definitely there in its ambience. Again, I invoke Eno, specifically, Ambient 1: Music for Airports. If you were a listener in 1978, I imagine Eno’s quietude would have been quite difficult to stomach in an atmosphere of Punk, Funk and Disco. Hartnell Greys occupy a similar territory; the only difference being that they happened upon it quite by chance and usually because of some initial creative weakness (usually the script or direction).

If Galaxy 4 existed in its entirety, it would likely be the best Hartnell Grey. Its scale is small, its portrayal of the planet being deliberately between the points of two spaceships, it has cute silly robots, and its monsters again aren’t really monsters (a growing theme here). In some regards, Hartnell Greys remind of those early Hartnell comics for TV Comics such as The Klepton Parasites and Moon Landing; their silver-age silliness adds a distinctive flavour and, like their TV counterparts, were made explicitly to be enjoyed in living rooms like the one from More Than Thirty Years in the TARDIS and the one they recreated in the Llangollen Doctor Who Exhibition with that creepy frozen mannequin boy hiding permanently behind the sofa.

Other Hartnell Greys include several bits and bobs from Season 1. It would be tempting to put Edge of Destruction in the mix but it’s too dark and uncomfortable to really fit the bill. Comfort is essential to the Hartnell Grey. The Sensorites is certainly a Hartnell Grey though this one does stretch even my own limits, not least as the only way to ever really experience it for me was in its VidFIRE format (this removes some of the warmth of the Hartnell Grey). The Keys of Marinus is a good example of a story that becomes a Hartnell Grey as the wheels of the programme gradually come off. Its scale may be vast, but the reality of its production trying to achieve it, with glorious resulting naffness, renders large chunks of it a Hartnell Grey. “You could have lent her hers”, is the rallying cry of the Hartnell Grey, and I have long daydreams about acidic tidal pools, laboratories with mugs and statues with naked arms, For a good, further example of what I’m talking about, if The Daleks was a Hartnell Grey (which it definitely isn’t), it would be seven episodes’ worth of just the scene of The Doctor looking towards the city from the rocks while Susan dramatically overreacts at the possibility of his being seen.

Other stories totter on the precipice of being a Hartnell Grey but don’t quite make it. Planet of Giants is too ambitious (and arguably achieves its ambitions in spite of the episode splice) to really count (and was again VidFIRE’d, boo), though its scale (literally) is pleasing. The Web Planet certainly has Hartnell Grey elements in it but its ambition is just too absurd to not applaud in some way (though on another day, I’d lump it in here with ease, usually when I’ve recently re-watched it and adored every Vaseline-covered second of it, to turn a phrase…). The Celestial Toymaker is too strange and weirdly creepy to count (though it does seem to give rise to similar reactions to these stories from some fans, though the villain is too interesting to count it). Individual episodes of The Chase count as well but not the story taken as a whole. A full four-part story on Aridius or Mechanus though? Phwoar.

Perhaps if I cared more about The Savages I’d count it as a Hartnell Grey but the story has really passed me by; this a taste developed as a naive child, not in hindsight, and its audio was a late addition to my collection. Instead, I’d say The Ark is the last truly great/naff Hartnell Grey. Again, some of its scale (of production) feels a little too big for it to properly qualify (it has an elephant!) but any story with a Security Kitchen could be nothing else but a Hartnell Grey. Its latter two episodes are especially high grade Hartnell Grey, particularly its space sequences which are wonderful. The Mondoids conspiring in over-elaborate, ever extended sentences is weapons grade Hartnell Grey as well.

The spirit of the Hartnell Grey did briefly live on into Patrick Troughton’s era, again explaining people reaching for the smelling salts/local asylum phone numbers when I tell of my love for The Dominators, The Krotons and the first episode of The Wheel in Space. But naff Who developed a different flavour in later years. They later embodied a 1970s brownness: think Underworld, The Invasion of Time and The Armageddon Factor. But I certainly don’t enjoy them on the same ambient, cosy level of these silly stories, however. I’m happy to admit as well that I’d take old Cocky-Lickin’, a trundling Chumbley and the Security Kitchen any day of the week over any of the recent fare; bells, whistles, Giga-decibel Murray Gold, endless crying and all. As Barbara wisely pointed out in The Space Museum, “It’s the sort of silence you can almost hear…”. That’s what a Hartnell Grey is.